Why are frontiers more conflict-prone—and what is the relevance of historical political economy for answering this?

By Adeel Malik (University of Oxford), Rinchan Ali Mirza (University of Kent, UK), and Faiz-ur-Rehman (IBA, University of Karachi)

“Frontiers were, indeed, the razor’s edge upon which hung suspended the modern issues of war and peace, life and death”, Lord Curzon, “Protectorate and Hinterland”, Romanes Lecture, University of Oxford (1907).

“To speak of frontier governmentality in the modern world, then, is to speak of a long history of violence.'' Benjamin Hopkins, Ruling the Savage Periphery: Frontier Governance and the Making of the Modern State. Harvard University Press (2020).

For centuries, borderlands have been cauldrons of rebellion, resistance, and violence against the state. Recent data confirms this: a 2024 OECD Report found that peripheral regions of modern states experience significantly more conflict than central territories. Since 2010 the intensity of such violence has also increased in border regions, which have proven to be fertile grounds for armed insurgencies. Why do frontiers tend to experience greater violence against the state than heartland territories? In our research, we offer a deep explanation rooted in the history of colonial rule. Imperial powers often ruled their frontier territories, which were typically liminal spaces on the edges of empires, differently from the core colonial regions. Such “rule of difference” typically rested on distinct administrative and legal practices. Historian Benjamin Hopkins describes this distinct frontier rule as “frontier governmentality”—a laissez-faire institutional arrangement where the state’s presence was relatively thin, authority was delegated to local elites, and frontier residents were cut off from formal institutions of conflict management (e.g. courts, police, and electoral politics). Such frontier buffer zones effectively operated under conditions of partial sovereignty whereby colonial rulers shared with local elites the state’s power over coercion and social control. It was thus a highly personalized form of rule where the state delegated even greater power to local elites than was the case under indirect rule. These arrangements, rooted in colonial cost-benefit calculations (e.g., high governance costs or external threats), became a global template, applied from British India’s North-West Frontier to Kenya’s northern borderlands. Crucially, this institutional legacy endured post-independence, creating uneven territorial governance within former colonies.

While historians, anthropologists, and political scientists have examined the enduring legacy of frontier rule, its role in shaping contemporary conflict has not received any empirical attention. Investigating this relationship in a rare empirical context, we argue that while frontier rule can sustain social order over long periods, it is especially vulnerable to violence when disrupted by external shocks. As a distinct mode of governance, it relied on minimal state presence and elite mediation—trading institutional depth for fragile stability. This limited resilience stems from several factors. Frontier populations often maintained only a tenuous connection to the state due to its shallow reach, shaping state–society relations in profound ways. Unlike residents of non-frontier regions, those in frontier areas typically lacked access to formal institutions such as courts or electoral systems, instead depending on traditional dispute resolution led by local chiefs and elders. In contexts where social order rests almost entirely on elite mediation, any threat to those elites risks creating an institutional vacuum—one that can quickly become fertile ground for violence. In the absence of institutionalized channels for negotiation and competition, disaffected groups are more likely to challenge the state’s legitimacy through sovereignty-contesting violence.

The setting: British India’s Northwestern Frontier

Our research draws on one of original and classic cases of frontier rule established in British India’s North-West Frontier Province, bordering Afghanistan. In 1901, the British divided the province into settled districts and frontier areas, both inhabited by Pashtuns but governed under sharply divergent institutional regimes. For over a century, the frontier tracts were ruled—first by the British Empire, then by Pakistan—through local elites rather than courts, police, or bureaucracies. While settled areas had formal administrative structures, legal protections, and limited political representation, frontier regions operated under minimal state presence, relying on tribal elites, informal jirgas (Councils of Tribal Elders), and paramilitary forces. This stark institutional discontinuity was aptly captured by Sir Olaf Caroe, a colonial-era governor, who observed that “the line of administration stopped like a tide almost at the first contour” of the frontier. This enduring “rule of difference” legally disenfranchised frontier populations and excluded them from judicial and electoral systems. It persisted long after independence, with frontier areas remaining legally and politically marginalized well into the 21st century, despite formal reforms in 2018 that have yet to produce meaningful change on the ground.

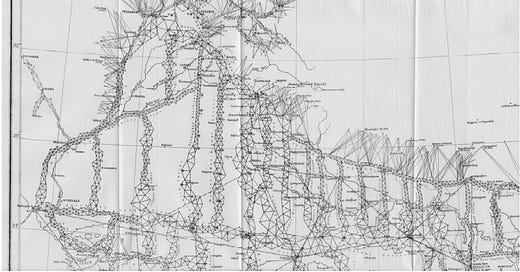

Although frontier rule was widely applied across colonial contexts in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, its long-term effects on conflict are difficult to assess because frontier boundaries were often non-random, shaped by natural geography (e.g. waterbodies, rivers, or mountains), pre-colonial borders, or mapped with scientific precision. Pakistan’s North-West Frontier offers a rare exception. While broader strategic considerations may have motivated the British to establish a frontier buffer zone, we argue that the actual placement of its border was determined in a haphazard and arbitrary manner. Drawing on a rich body of historical evidence, we show that the British employed a narrative-based, non-scientific cartographic regime in mapping these frontiers. Unlike the rest of British India, which relied on precise trigonometric surveys, the frontier regions were subjected to a hurried and improvised route-mapping, relied on inconsistent local knowledge, and were shaped by the discretion and idiosyncrasies of surveyors, guides, and administrators (see Figure 1). This imprecise method reflected colonial perceptions of the frontier as a mysterious, adventurous, and unknowable buffer zone rather than a space to be accurately mapped and systematically governed. Historian Thomas Simpson aptly characterizes this process as “cartographic anarchy”, underscoring the “chaos and heterogeneity of survey work on the ground in British India”. Crucially, the frontier rule border did not align with pre-colonial boundaries or natural geographic features. While some broad differences exist between frontier and settled areas, the internal terrain of the frontier varied significantly—undermining any simple ecological divide, such as the hills-versus-plains distinction proposed by James Scott.

Figure 1: This figure presents the trigonometrical survey map of British India from 1881. The map highlights a stark contrast: the northwestern frontier is represented with elongated lines, indicating imprecise mapping, while the rest of British India is mapped precisely using triangles. Source: General Report on the Operations of the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, 1881.

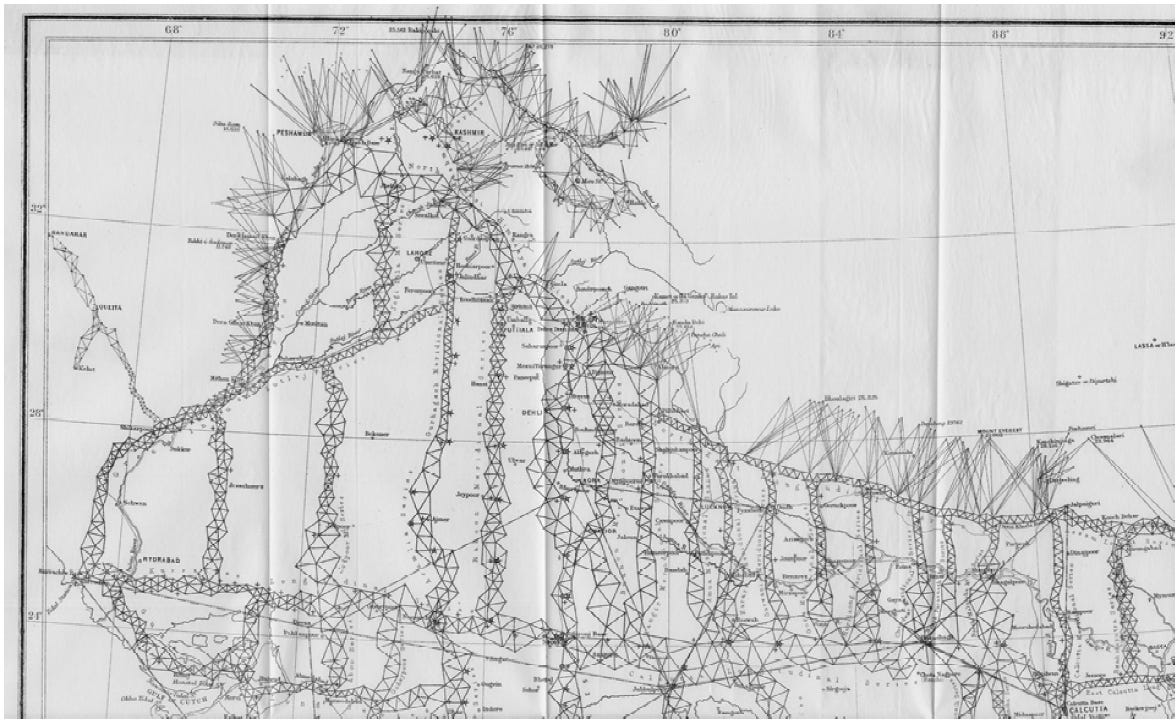

Our empirical analysis leverages this arbitrarily defined historical border in a spatial regression discontinuity design to examine whether historical exposure to frontier rule predicts contemporary conflict in closely situated regions. In this regard, we utilize a geo-coded data on conflict against the state, measured at a highly granular level (i.e., 10 x 10km grid-cells) during the period 1970-2018. Figure 2 shows the area of study and visually represents the spatial distribution of conflict incidents.

Figure 2: Panel A shows the area of study within which our sample is restricted. It encompasses all those areas that lie within a 50-km buffer zone around the FR boundary. Panel B shows the spread of conflict incidents against the state from 1970 to 2018. Each black dot represents an attack against the state (defined here as military personnel or installations) and the red line denotes the historical FR border (as of 1901) separating frontier areas (left side of the border) from settled districts (right side of the border).

Frontier rule and conflict

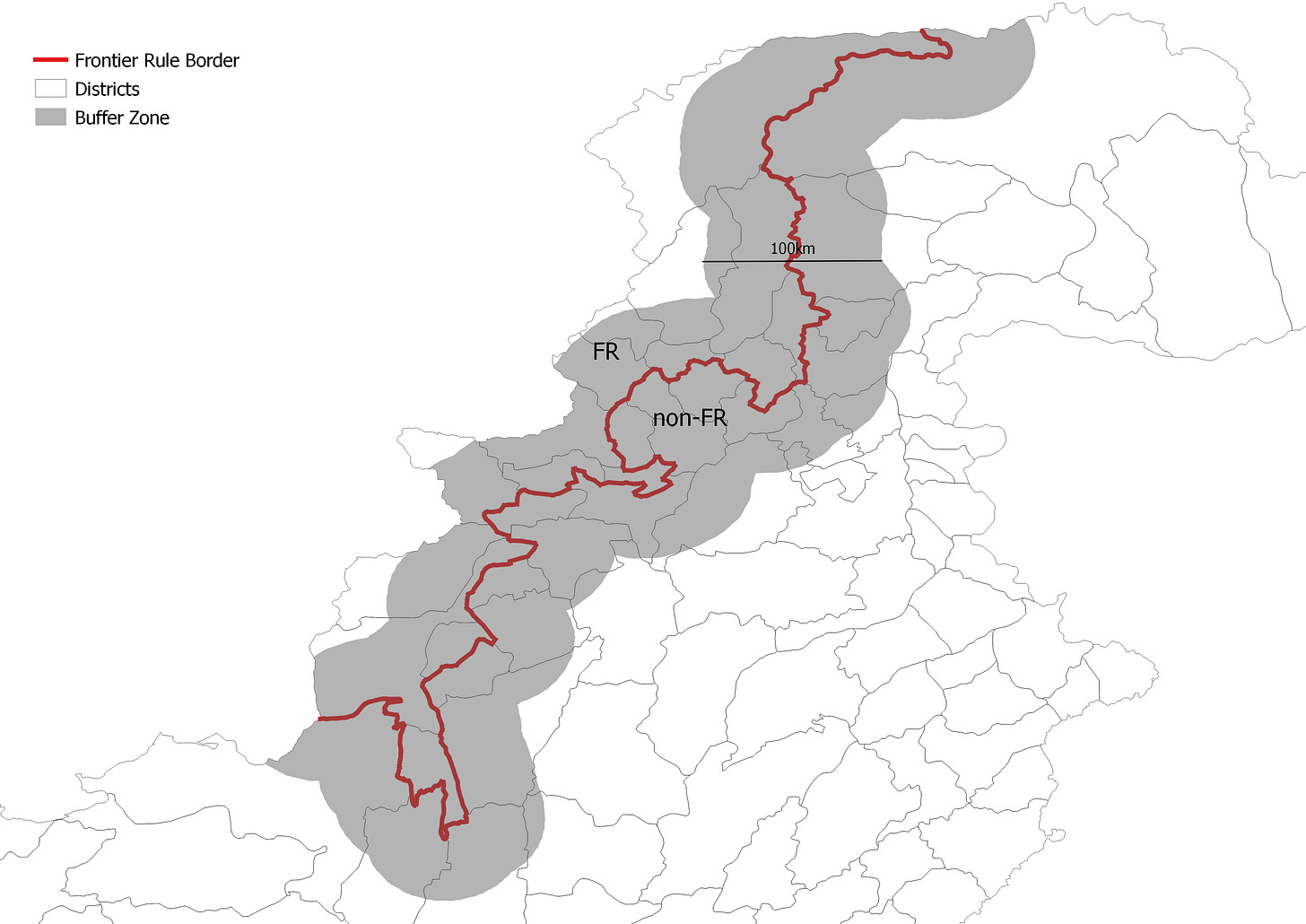

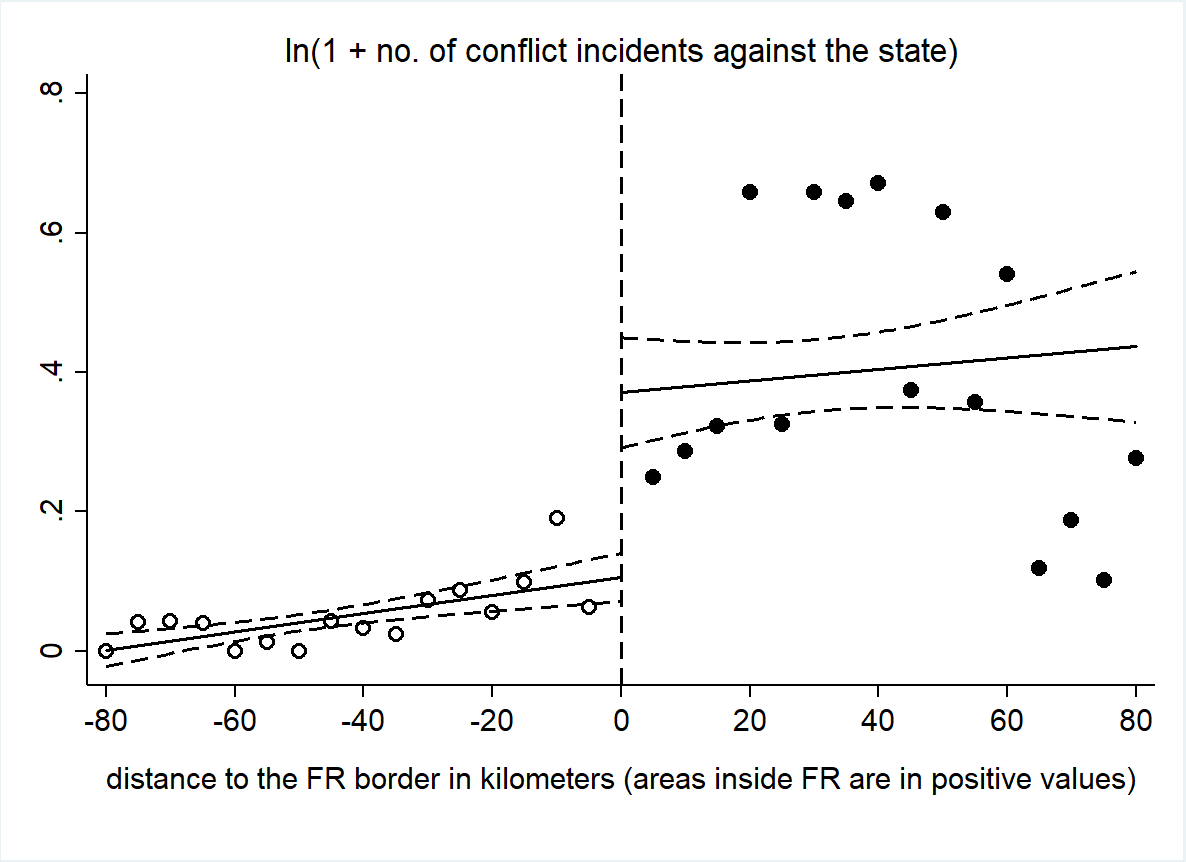

Our results show that, on average, between 1970 and 2018 areas that fell just inside the historical frontier border witnessed a significantly higher incidence of conflict against the state than areas just outside the frontier border (see Figure 3). The effects are substantial: residents just inside the border demarcating frontier rule were 57 per cent more exposed to conflict than those just outside the border. To ensure that this difference is not due to other underlying factors, we test for and find no major differences across the border in geography, climate, population, or social structure (e.g. ethnicity and religion). We also show that areas on both sides of the FR border display no significant differences in relevant historical dimensions, such as pre-colonial conflict and population density.

Figure 3: Binned scatterplot (16 bins of size 5km each) of the unconditional relationship between conflict against the state and distance to the FR border. The y-axis reports the natural log of 1 plus the incidents of conflict against the state. The x-axis reports the distance (in km) from the FR border for areas under FR and non-FR. The border itself is at km 0 with positive values indicating km inside the FR territory.

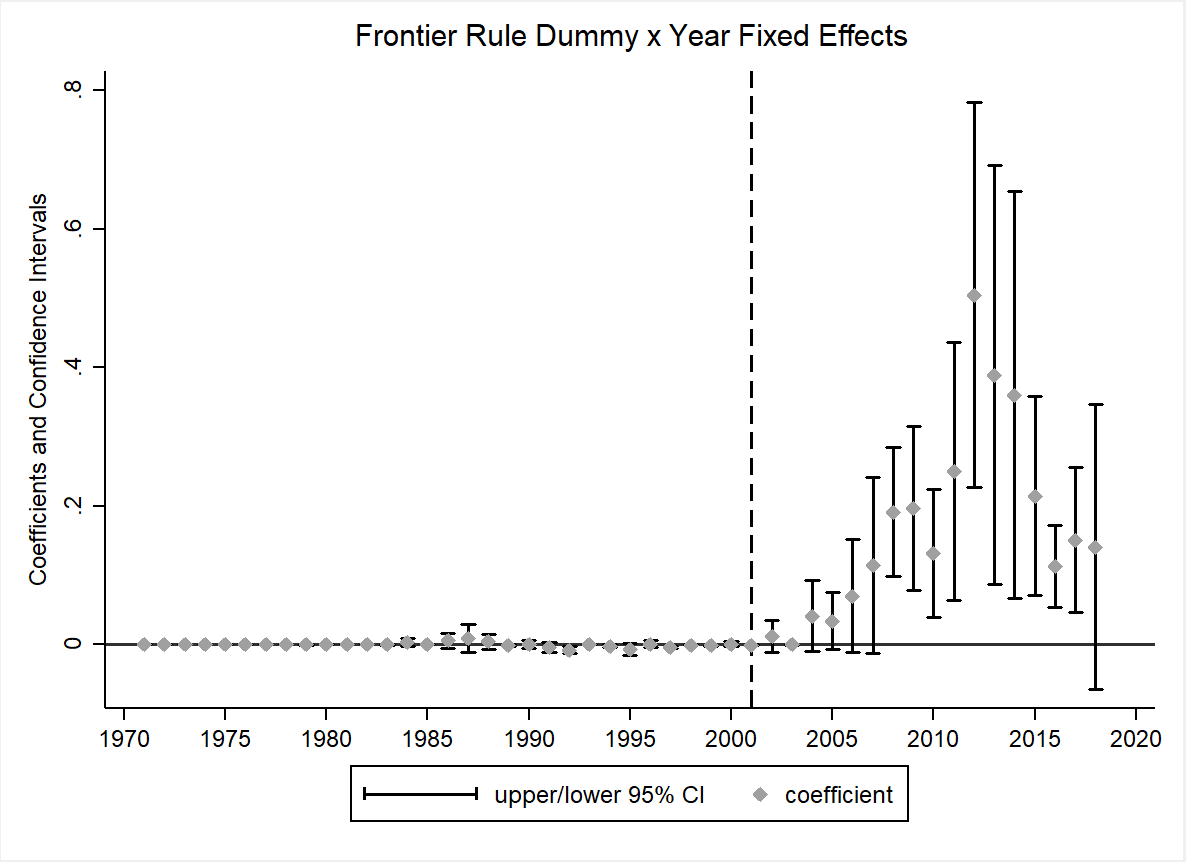

To unpack our results and probe their substantive meaning, we explore the temporal dimension and show that this differential conflict incidence between frontier and non-frontier regions is a feature of the post-9/11 period (see Figure 4). Specifically, the impact of frontier rule on conflict emerged only after the 2001 U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, which was widely unpopular in Pakistan’s Northwestern regions where it was seen as an unjustified attack against ethnic Pashtun brethren across the Afghan border. The year 2001 marked a watershed moment when, under external pressure, Pakistan’s military ruler reversed the country’s decades old Afghan policy, joined the U.S.-led War on Terror, and extended the military’s presence into frontier areas. While initially the Pakistani military only increased its physical presence on the border to prevent Afghan fighters spilling over into Pakistan, it was nevertheless seen as an alien force doing the bidding of a foreign power.

Figure 4: This figure plots the point estimates and confidence intervals of the frontier rule (FR) dummy interacted with year fixed effects for an event study specification that also includes district and year fixed effects. The coefficient for the base year (1970) was set to zero and is not shown in the figure. The analysis is conducted at the sub-district (tehsil) level. The sample includes all sub-districts of Pakistan. The coefficient on the FR interaction dummy progressively increases from 2001 onwards until it becomes statistically significant in 2008 and reaches its peak in 2012.

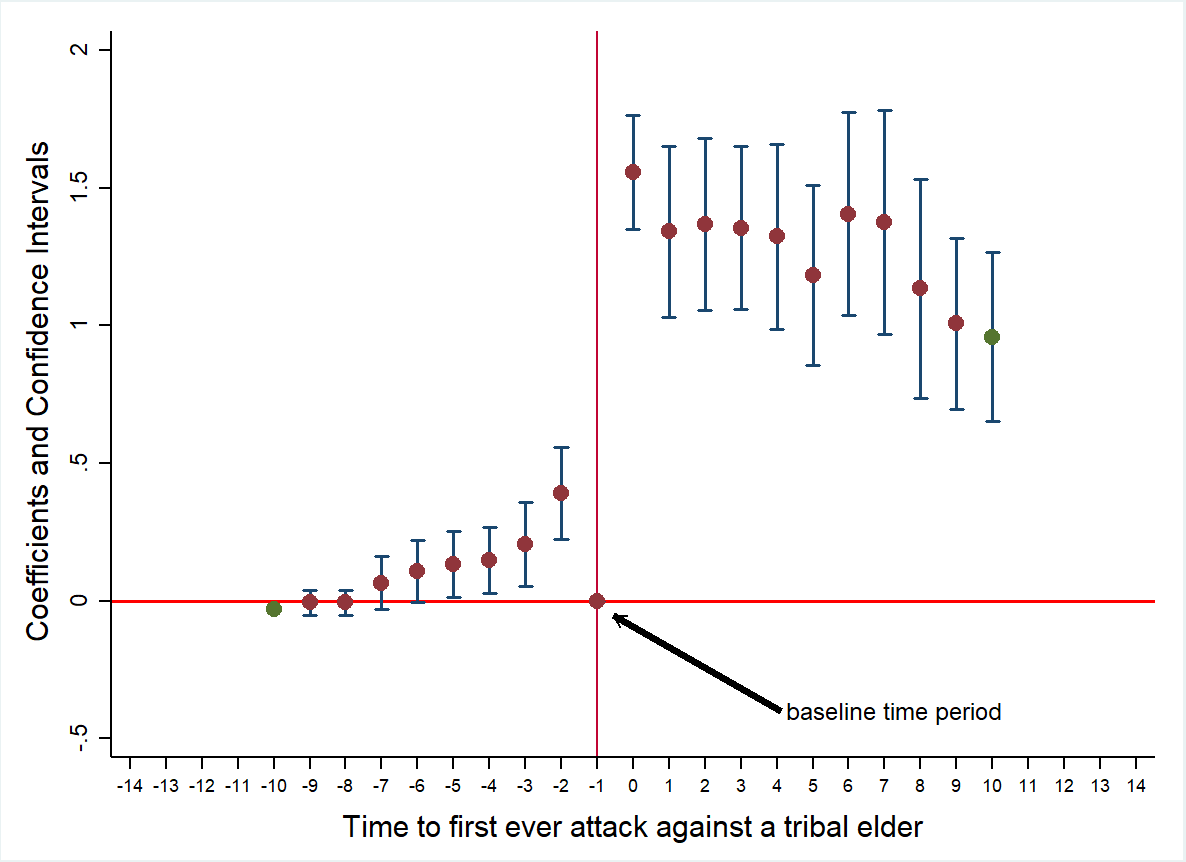

While the post-9/11 grievance against the state was present in both frontier and non-frontier regions, it translated into heightened conflict in frontier areas that had historically suffered from an institutional void. A key driver of this escalation was the targeted elimination of tribal leaders—critical intermediaries between the state and local communities—whose removal, in the absence of formal conflict-resolution mechanisms, deepened instability and violence. To lend empirical credence to this line of reasoning, we offer two types of evidence. Firstly, we use data from a nationally representative survey to shed light on the three dimensions that make frontier rule vulnerable: absence of formal institutions of conflict management, greater dependence on elite intermediation, and low trust in state institutions among frontier residents. Secondly, we empirically demonstrate how the strategic elimination of tribal elites unravelled social order in frontier areas (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: This figure plots the coefficients and confidence intervals for the estimated relationship between the first-ever attack on a tribal elder and the overall level of conflict in the same grid cell. The dependent variable is ln (1 + all conflict incidents). Estimates are from a regression model that allows for effects before, during, and after the first-ever attack on a tribal elder and includes district and year-fixed effects.

Recognizing the complexity of insurgency-based violence, we entertain multiple competing explanations behind the post-9/11 rise in violence against the state in the frontier rule areas. Foremost among these is the possibility of a conflict spillover from Afghanistan. We show that an overwhelming majority of attacks against the state were carried out by local outfits rather than Afghan-based militants. Next, using a variety of empirical approaches, we also rule out the potential role of U.S. drone attacks and Pakistani military operations in the area (which also constituted an important income shock for local populations). We show that both drone attacks and military operations against terrorist outfits were an endogenous military response to the rise of violence, which pre-dated the original post-9/11 uptick in violence. Finally, we address concerns that persistent under-provision of public infrastructure in geographic peripheries like Pakistan’s north-west frontier may be driving anti-state violence. We find no statistically significant differences in infrastructure, whether modern (roads, waterways, health centres) or historical (colonial railways, Mughal roads, pre-colonial Islamic trade routes), between frontier and non-frontier areas.

Implications of our study

We conclude this blog by highlighting the broader relevance of our study for three important areas: (a) understanding violence in other frontier regions; (b) contribution to relevant academic literatures, and (c) historical political economy.

Our findings speak to a much broader story than just Pakistan’s frontier regions. Similar patterns of “frontier rule” have existed in places like Northern Kenya, Northern Nigeria, and Iraq’s Basra region—areas where colonial powers created special systems of governance and carved out hybrid zones where state authority was always partial, always negotiated. These arrangements, built during the 19th and early 20th centuries, often kept the peace—until droughts, wars, or political shocks exposed their fragility. Today, as climate change and geopolitical rivalries strain borderlands worldwide, understanding these institutional legacies isn’t just an academic curiosity but also relevant for policymakers. It’s a warning: in regions where the state never fully established control and where relationships between the government and local communities remain fragile, even isolated shocks can turn peripheries into powder kegs. Crucially, resolving conflict in such frontier regions isn't just a matter of military action. Instead, enduring peace requires a more essential and difficult task: confronting deep-rooted institutional gaps and rebuilding trust where, for generations, the state has been absent or alien.

Our research has important implications for the conflict literature, which emphasizes the role of institutions but has yet to fully examine the impact of specific legal and political structures. As a comprehensive review by Blattman and Miguel argues, key institutional features are ‘yet to be carefully defined and measured’ in the conflict literature. Furthermore, as they note, the impact of institutions on conflict can be conditional on other factors. To this end, our research underscores how the interaction between historically embedded governance systems in frontier areas can interact with geo-political shocks to fuel violence against the state. Our work also directly contributes to a growingly niche literature on frontiers and their influence on development outcomes, including long-run inequality, economic geography, public infrastructure, and culture and politics.

Our work also connects with emerging conceptual and methodological debates in historical political economy (HPE). Our work moves beyond persistence studies, which simply trace the long-run impact of historical legacies, to offer more nuanced evidence on “why” and “how” history matters for contemporary violence. In this regard, our work aligns with the emerging focus in HPE on historical contingency and “time-varying persistence”, demonstrating how historical legacies can remain latent until activated by specific shocks—such as, in our case, the geopolitical shock of 9/11. We also underscore the importance of paying attention to timing and sequence, which can be critical for making causal claims in the context of insurgency-based violence where several mutually reinforcing factors are triggered in a sequence drawn out over time. Paul Pierson’s advice is particularly relevant here; he argues that “long-term outcomes of interest depend on the relative timing of important processes [. . .] A variable’s impact cannot be predicted without an appreciation for when it appears within a sequence unfolding over time.” One of our final learnings while working on this project was the importance of qualitative historical evidence in validating natural experiments that rely on the assumption of “as-if-random” borders (e.g., in spatial regression discontinuity designs). In this context, a deep dive in history is not a luxury but a necessity, especially in the light of recent work that has overturned the prior academic consensus on randomly-defined colonial borders in Africa.

Authors:

Adeel Malik is associate professor of development economics at the University of Oxford and Globe Fellow in Economies of Muslim Societies at the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies. His research focuses on the political economy of development in Muslim societies, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa. His recent work on Pakistan has probed the deep and enduring legacies of colonial rule. He has published in esteemed academic journals, including Journal of the European Economic Association, Journal of Development Economics, Journal of Historical Political Economy, the European Journal of Political Economy, and the Journal of Democracy. Additionally, his research has been featured in high-profile journalistic outlets such as the CNN, Financial Times, the New York Times, the Washington Post, Project Syndicate, Foreign Policy, and Foreign Affairs.

Rinchan Ali Mirza is a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Economics at the University of Kent, having previously served as a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Namur’s Center of Research in the Economics of Development from 2016 to 2019. He holds a DPhil and an MPhil in Economics from the University of Oxford, as well as a BSc in Mathematics and Management from King’s College London. His research spans economic history, political economy, the economics of religion, development economics, and applied microeconomics. Dr. Mirza is a faculty fellow at the Association for Analytic Learning about Islam and Muslim Societies (AALIMS), a research fellow at the Centre for Economic Research in Pakistan (CERP), and a founding member of the Development Economics Research Centre at Kent (DeReCK), reflecting his commitment to rigorous, policy-relevant research on development and the Muslim world.

Faiz Ur Rehman is an Associate Professor of Economics in the Department of Economics at IBA. He holds a joint Ph.D. degree in Law & Economics from the Universities of Bologna, Hamburg, and Erasmus Rotterdam, acquired under the Erasmus Mundus Doctorate Fellowship. He joined IBA in 2021, and prior to that, he was associated with Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad. His areas of interest encompass the economics of conflict, political economy, and applied economics. Presently, his research focuses on projects including Frontier Governmentality, Frontier Rule and Long-Term Development, Conflict and Early Human Capital, as well as Firms' Public Credit and Default Rate. His instructional portfolio at IBA covers Macroeconomics, Applied Economics, and Institutions and Development.