Tilly Goes to Church: The Medieval and Religious Origins of the European State

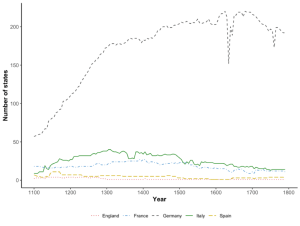

How did the state arise in Europe? The canonical answer is Charles Tilly’s: “war made the state and the state made war.” The starting point is the fragmentation of territorial political authority in Europe after the collapse of the Carolingian empire in 888, and the ambitions of rulers in the early modern (1500-1700) era. To expand their rule, monarchs and princes fought bitter wars with other other—and to fund this increasingly costly warfare, they extracted taxes. Domestic institutions such as state administrations, fiscal offices, and parliaments arose in response to these needs. In these “bellecist” accounts,[1] rulers who succeeded in building up the administrative and military apparatus of war went on to consolidate their territorial gains and ensure the survival of their states. These relentless pressures eventually meant fewer and bigger states, from as many as 500 independent states in Europe in 1500 to 30 four centuries later.

In a current book project, I take Tilly to church, and question each of these core pillars of the bellecist story. I show that roots of many state institutions are found in the medieval era, not the early modern. Fragmentation was not simply a post-imperial legacy, but a sustained and deliberate policy. The biggest rival for an ambitious medieval ruler was not another monarch, but the Roman Catholic Church, the most powerful and wealthy political actor in the medieval era (1100-1350). Secular rivals struggled with the papacy—but they also adopted its effective institutional solutions. As a result, familiar domestic institutions such as legal systems, parliaments and concepts of representation, direct taxation, and chanceries all emulated church templates.

This revisionist account of state formation builds on recent work that explores the deep historical causes and consequences of urbanization, the rule of law, the Crusades, the rise of universities, and parliaments.[2] It emphasizes, however, the role of the Church as both the critical rival for medieval monarchs, and the main source of institutional and conceptual innovations for these would-be state builders.

The Church as Rival

The fundamental rivalry of the medieval era was the unrelenting conflict between popes and rulers over authority, territory, and sovereignty. The Church was at its most powerful from the late 11th to the 14th century. Starting in the 1050s, the papacy consolidated its power within the Church, and papal power grew immensely during the 12th and 13th centuries. A spectacular example is Innocent III (r. 1198-1216.) A proponent of papal supremacy and an ambitious leader, Innocent threw himself into temporal politics, crowning and deposing kings, and settling disputes. He invigorated an earlier, 5th century concept of plenitudo potestatis, the “fullness of power,” which he used to assert universal papal jurisdiction over all Christianity.

Why was the Church so powerful? First, it was wealthy. The medieval Church was the biggest landowner in Europe, with anywhere from 25% to 40% of land across Europe in Church hands.[3] The church also taxed both clergy and laity alike, pioneering direct taxation and new compliance strategies.

A second source of power consisted of the church’s human capital: literate clergy, legal expertise, extensive documentation and archives, and administrative experience. Clergy served throughout the nascent state administrations (“clerks” are so called because early officials were clerics.) Bishops served as high-ranking royal officials: regional governors, counselors, chancellors, judges, and diplomats.

Finally, the Church’s power derived from its moral authority. It was deeply present in everyday life as both a religious and secular authority. Above all, it offered salvation—a promise of an eternal life and divine mercy that no secular ruler could match. The papacy also wielded the power to excommunicate rulers and place entire countries under interdict, excluding them from the religious community and the possibility of redemption.

Territorial Fragmentation

One result of this rivalry was the continued territorial and political fragmentation of Europe. A broad scholarly consensus emphasizes that this atomization is the foundation for subsequent political and economic development of Europe.[4] Subsequent medieval governance was a disjointed system of local authority and incomplete territorial control, a raft of principalities, ill-defined kingdoms, and territories controlled by warlords.

Yet this fragmentation was no accident. Popes worked assiduously to keep any one ruler from getting too strong and reassembling Charlemagne’s empire. The Church deliberately played rulers against each other, and used doctrine, intimidation, and wars by proxy to ensure that no powerful rival could arise that might threaten its political or territorial interests. The papacy’s chief target was the Holy Roman Empire (as the eastern post-Carolingian lands became known by the mid-13th century.) The empire repeatedly sought to control both northern Italy and Sicily, in effect encircling papal territories in a threatening pincer movement. Popes made successive efforts to take states out of the Empire’s sphere and into their own, by subsidizing allies, excommunicating unruly leaders, and using both legal arguments and wars. For their part, by continually waging war with the papacy, medieval emperors were distracted, and unable to prevent bishops and princes from gaining judicial, territorial, and political power, effectively precluding the consolidation of central rule in the Empire.[5]

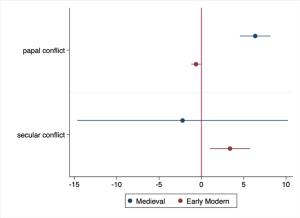

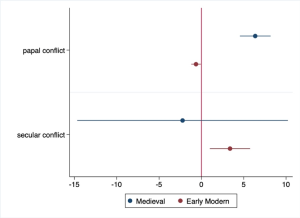

Papal scheming rather than secular conflict, then, fragmented territorial authority in medieval Europe. I collected data on conflicts with the papacy, augmenting existing data from Dincecco and Onorato on secular conflict, and compared medieval to early modern periods. As the figure below shows, conflict with the papacy is closely associated with fragmentation in the medieval period—but has the opposite correlation in the early modern, when popes and the Church itself lost much of its power. Conversely, secular conflict is positively associated with fragmentation in the early modern period, but not earlier.

The resulting territorial fragmentation lasted throughout the early modern period, as Abramson shows, contrary to the bellecist accounts. It was driven largely by the atomization of the Holy Roman Empire. It did not diminish thanks to early modern war and territorial consolidation, but persisted until German and Italian unification in the mid-19th century.

Papal Templates, State Institutions

If rivalry with the church offered one motive for state building, the church also offered the means: it provided multiple institutional templates: administrative precedents, legal advancements, and conceptual justification. These templates, in turn, were transmitted through church decretals, clergy serving in the courts and chanceries, and bishops sitting close to the royal ear in administrations, councils, and national assemblies.

The church taught lay rulers how to collect taxes, answer petitions, keep records and accounts, interpret the law, and hold councils that would provide valuable consent. The tripartite division of labor in courts– a Camera to collect and audit taxes, a Chancery to answer petitions and promulgate answers, and a judiciary to issue judgments—followed the centralization and specialization of the papal administration that began in the mid-11th century. Royal chanceries used language adopted from the papal chanceries, the same formulas for documents, and even the same script. Church precedents such as the Saladin Tithe of 1188 showed secular rulers how to tax directly, and how to do so effectively, using emissaries, profit-sharing, and auditing procedures, long before the early modern era. Here, the church influenced the timing of state institutions as well: where the church needed allies, it did not interfere with institutional centralization, as in England. Where the church had earlier fragmented authority, as in the Holy Roman Empire, centralized state institutions arose far later and more precariously.

The rediscovery of Roman law in the 1070s, and the systematization of canon law in the 1140s transformed Europe. Both lay and canonical experts reinterpreted private Roman contract law, and both civil and canon courts competed for custom and jurisdiction. Bishops staffed both. The active participation of clergy in justice, in turn, meant that the church could change legal procedure: trials by ordeal ended in Europe once the 1215 Fourth Lateran Council outlawed the spilling of blood by clergy, for example. The huge new demand for legal training led to the flowering of universities, and both popes and monarchs vied to charter universities.

Parliaments owe much to the church as well. Their medieval golden age was from 1250 to 1450, when they advised and legitimated kings (see Jared Rubin’s book on the need for “legitimating agents”) adjudicated disputes, and consented to royal policy. They thus predate the 15-16th century military revolution that necessitated taxation (and parliaments) in bellecist accounts. Critical principles that allowed parliaments to advise the king and articulate consent to taxation and other policies all derive from early medieval church practice and canonical reinterpretations of Roman law. These include the need for consent of those affected by a policy (quod omnes tangit, ab omnibus approbetur), constituency and corporate identity (universitas), full and binding powers of representatives (plena potestas), and majority rule (maior et sanior pars).

The State Triumphant

The irony is that the church ordained its own fall from grace: in battling monarchs, the church led these rulers to sharpen their own legal arguments and buttress their administrative and legal infrastructure. Church templates allowed rulers to develop increasingly powerful state institutions. Monarchs no longer depended on ecclesiastical personnel: they had legal experts and capable administrators of their own, trained in the same universities the Church supported. The very political fragmentation that the church fomented meant that when the Protestant Reformation took off, individual princes and lords could protect the new rival religion from Catholic counter-reaction. In winning battles, the Church lost the war.

—

[1] Tilly, Charles. 1992. Coercion, Capital, and European States: Ad 990-1992. is one of many works in this tradition: see the review by Dincecco, Mark and Wang, Yuhua. 2018. “Violent Conflict and Political Development Over the Long Run: China Versus Europe,” Annual Review of Political Science: 341-358.

[2] For a review of this literature, see see Grzymala-Busse, Anna. 2018. “Beyond War and Contracts: The Medieval and Religious Roots of the European State, Annual Review of Political Science, 19-36.

[3] These enormous land holdings were the result of accumulation in the 7th through 10th centuries, with voluntary offerings, property transfers, and bequests. The Church retained these with the family regime it introduced: for example, children born to clerics were by definition illegitimate and could not inherit, leaving property in church hands.

[4] Walter Scheidel focuses on the role of fragmentation in European development and reviews the enormous literature. See Scheidel, Walter. 2019. The Escape From Rome: The Failure of Empire and the Road to Prosperity. Princeton: Princeton University Press, and especially pp 357-60.

[5] The Empire had not established central taxation, administration, or a national assembly until around 1500.