The Why and How of Historical Psychology

By Mohammad Atari

In the heart of the Islamic Golden Age, the streets of Baghdad were alive with a symphony of diverse languages and the bustling exchange of ideas from many corners of the world. At the epicenter of this intellectual culture stood the House of Wisdom, a beacon of knowledge that drew scholars, thinkers, and innovators from different places to share, debate, and expand the frontiers of knowledge. Many scholars carefully translated and examined Byzantine, Persian, Greco-Roman, and Indian texts. Among these scholars was a figure whose insights into the human body and psyche would transcend time and geography: Avicenna, known in the Islamic world as Ibn Sina. His seminal work, “The Canon of Medicine” (see Figure 1) is filled with a rich body of medical knowledge, often based on or wholly recombination of earlier civilizations’ body of work.

Avicenna’s approach to healing—a revolutionary concept that combined the physical with the psychological—reflected a profound understanding of the human condition. In his approach, the health of the mind was inseparable from the health of the body, a belief that guided physicians in the hospitals of Baghdad. These institutions were not merely places of healing; they were sanctuaries of reflection, where the strum of the oud and the tranquil murmur of flowing water from courtyard fountains were perceived to offer solace to both the ailing and the weary.

The city has undergone significant transformations since its Golden Age, when Baghdad was celebrated for its dynamic scientific and technological debates and drew scholars globally in pursuit of knowledge. This raises intriguing questions: Can the collective psychology of people shift over historical periods? What about individual psychological characteristics? Or, even more fundamentally, can our basic cognitive functions and brain structure change? The emerging field of “Historical Psychology” seeks to explore these changes, their origins, and their consequences (Atari & Henrich, 2023; Muthukrishna et al., 2021). In this piece, I make the case that all these aspects of psychology, ranging from large-scale institutions to gut-level intuitions and neural constitutions, co-evolve over historical time.

Historical psychology is the study of mind and behavior through historical records and artifacts. This emerging discipline examines how populations’ psychological makeup varies over time and how the roots of our contemporary psychology run deep in historical processes (Schulz et al., 2019). Historical psychology can help us understand how people in the past (i.e., the dead) thought, behaved, and felt, and how their psychology shaped various economic and political outcomes. It is a window to the past humans and helps us understand the origins of our emotional tendencies, cognitive processes, and behavioral outcomes.

For example, historical psychology can tell us how people in Baghdad in the 11th century felt about different social phenomena, how often they violated norms or punished rule breakers, how frequently they talked about other religions, and what cultures they were most heavily influenced by. It is difficult to study some of these topics because, unlike contemporary humans, we cannot ask dead people to fill out questionnaires, participate in behavioral economic games, or come to the lab for social psychological experiments. However, we do have access to their psychological fingerprints, often bequeathed to us in texts. Therefore, text analysis represents perhaps the most important methodology in historical psychology. Qualitative analysis of written texts has a long tradition in social sciences, but new methods in quantitative text analysis offer a unique approach to measuring the psychology of the dead (Atari & Henrich, 2023).

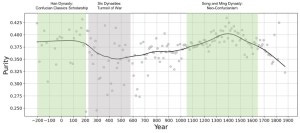

Psychologists have started adapting methods from Natural Language Processing (NLP) to quantify historical-psychological change. For example, Greenfield (2013) analyzed the relative frequencies of words associated with individualism and collectivism in the last two centuries in American English books, finding that individualism (e.g., focus on individual uniqueness and competition) increased with the increase in urban populations and the decline in rural populations. In a recent study, Choi and colleagues (2022) created a threat dictionary, a linguistic instrument designed to assess threat levels in text. They validated this tool by correlating its assessments with actual threats in recent American history, including violent conflicts and disease outbreaks. Analyzing newspaper data covering a century, they observed that shifts in perceived threats correlated with stronger social norms, more collectivist values, increased support for incumbent presidents, declines in stock market prices, and reduced innovation. More recent NLP studies have developed more advanced techniques to extract various aspects of psychology from historical corpora (Chen et al., 2024, see Figure 2).

There is more than one way to do historical psychology. I can think of three, even though given that the field is in its nescient stages, more approaches might be born in the future. The first approach focuses on historical-psychological change. This approach shares many features with prior work on cultural change developed by cultural psychologists (e.g., Varnum & Grossmann, 2017). That said, cultural change researchers often limit their analysis to culture-related constructs (e.g., individualism, collectivism), but historical psychology may cover all psychological constructs. Quantifying historical-psychological change can either be used in causal inference models (e.g., Atari et al., 2022) or simply describe change over historical time with no causal claim (see Rozin, 2001). The second approach is what I call the “then-and-now” comparative approach: looking at historical processes can affect outcomes today. Unlike the first approach, here, researchers do not necessarily quantify change continuously. Given that a lack of information on continuous measures of psychology can cause an unknown black box, this approach requires more evidence and stricter comparative controls to establish a causal link (see Austin, 2008). The third approach is what I call the “time-traveling psychologist.” Here, psychologists take their contemporary tools (e.g., theories, measures) and conduct psychological studies on dead people, often by looking at their fingerprints (e.g., historical bodies of text, bioarcheological data, e.g., Kennedy et al., 2023). For example, if one analyzes Avicenna’s and his contemporaries’ writings to infer their thinking style, family values, religious devotion, or sexual attitudes, they are doing this form of historical psychology. These can be thought of as replication studies where the subject pool is dead people.

These approaches to historical psychology share some fundamental features: first, they are falsifiable. Second, they all take time seriously, though often with different temporal spans. Third, they are psychological in the sense that they focus on various aspects of emotion (e.g., shame or hate), cognition (e.g., memory or thinking), and behavior (e.g., aggression or innovation). Lastly, these approaches are informed by cultural evolution as an overarching meta-theoretical framework (see Muthukrishna & Henrich, 2019).

Some scholars of history, including quantitative historians and historical political economists, are already doing historical psychology without realizing it or calling it “historical psychology.” So, in a sense, historical psychology is a very “privileged” discipline; it was born into a wealth of existing knowledge about how aspects of psychology manifested or changed over historical time in different populations (also see Cole, 1996). In a sense, psychology has a lot of potential to study historical contexts or temporal change, but psychologists have a lot to learn from history, sociology, anthropology, economic history, and especially historical political economics. Collaboration between historical psychologists, historical political economists, and historians is imperative because it offers a multi-dimensional understanding of past events and peoples. Historical psychologists may contribute insights into the collective and individual minds of people, revealing the underpinnings of behaviors, affective processes, and decisions. Historians offer a rich narrative contextualizing these psychological and political-economic factors within historical contexts. Together, they can provide deeper insights into historical phenomena and the origins of contemporary human behavior.

Historical psychologists can bring important perspectives and theories to the table. Whether you want to examine the role of colonialism in state formation and democracy or investigate why some cultures fell behind in economic growth in the early modern period, you cannot ignore the psychology of the people who lived then — their perceptions, norms, attitudes, judgments, values, and more. There are large bodies of research literature on all such variables in psychology, and we can use (and adapt) them to better model how historical processes shaped our psychology, which in turn influenced political and economic outcomes (Henrich, 2020).

In conclusion, psychology is not static. Our emotions, judgments, and behaviors depend on the historical context in which we are embedded. For instance, comparing the psychological landscape of 11th-century Baghdad with contemporary times reveals significant shifts influenced by factors such as ecological changes, conflicts, migrations, and political systems, among others. Similarly, all populations around the world have seen psychological variations. This change is not limited to “surface-level” psychological outcomes; historical processes fundamentally change how we feel, think, and act. The new field of “historical psychology” studies these dynamics, drawing upon cultural-evolutionary theory and employing advanced methodologies like NLP. The future of the field is bright: more and more psychologists are realizing that history should be taken seriously in order to account for the substantial psychological diversity around the globe. As the field takes off, it becomes increasingly crucial to foster interdisciplinary collaboration and work with a wide range of scholars ranging from history and sociology to historical political economics and archaeogenetics.