The origins of state capacity

In a previous post, I discussed the challenges of conceptualizing and measuring state capacity. Today I want to talk about something related — how we measure state capacity also has implications for how we study its origins.

I noted in the post that building state capacity in the short run is inordinately hard because an effective state requires a range of technical capabilities such as bureaucratic power, informational capacity, and coercive capacity. So we often think of state-capacity as a “sticky slow-moving variable” which in turn has given us researchers the license to measure capacity as the outcomes it is expected to shape. For instance, some common measures of state capacity include per capita taxation and per capita GDP. It’s no surprise then that state capacity is used in most studies as a right-hand side variable shaping a range of outcomes notably economic development, public good provision and conflict.

Our collective belief that state capacity accrues slowly over time has focused our attention on macro-historical origins of state formation through wars, colonialism, geography and resource extraction. Much of this view of state capacity comes from our knowledge of state-building in Western Europe where historic wars, and political centralization led to a slow accumulation of state capacity. How then do we account for state-building without external wars? And what if any, even amongst the advanced industrial democracies of the West, was the role of social and political conflicts in when and how societies achieved consensus over investing in state-building? Put simply how do we study state-building as a strategic choice, and what factors beyond war shaped those choices?

Recent studies in HPE on state-building in a diverse range of cases from Mexico to Turkey to China and India offer clues.

Francisco Garfias studying Mexico finds that bureaucratic capacity is often dependent on the willingness of nonruling economic elites to cooperate with rulers. When nonruling economic elites threaten to seize power, rulers can be deterred from investing in state capacity essential for a range of functions including public goods and development. But when economic elites find themselves on the back foot, rulers can press their momentary advantage to invest in state capacity to expropriate in the present and to secure extraction in the future.

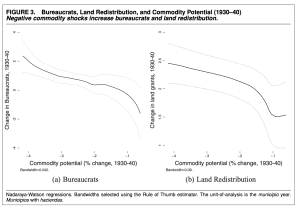

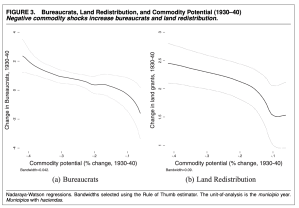

He shows using municipal-level data on land ownership and commodity price shocks (see figure 1 below) that during the Great Depression, negative price shocks resulted in greater land redistribution and greater investments in state capacity. A large muncipio that suffered a one standard deviation decrease in commodity potential witnessed an increase in government bureaucrats of 18 agents per 1000 residents. In this way, even in the absence of external threats, rulers strategically built capacity.

In India, I show that state capacity weakened around the period of the first elections held in Colonial India. Using district-level data I find that places where high caste elites were more dominants, tax avoidance grew, and the number of bureaucrats employed in the municipal bureaucracy declined in the decade after franchise extension. These results highlight how social conflict over caste dominance rather than economic inequality per se, weakened state capacity.

Both the Mexico and India findings highlight the importance of focusing on local bureaucratic presence as one important measure of local state capacity. By shifting the lens to bureaucratic power, these studies demonstrate how social and economic prerogatives played into elite calculations over investments into state capacity in the short-run. If you are interested in learning more about bureaucratic power, Scott has you covered in a terrific post on the usefulness and limits of using local bureaucratic presence as a measure of state capacity.

Beyond distributive conflict, two new papers on state-building in Imperial China during the Qing dynasty underscore how elite calculations factored into war-making.

In the first paper, Ying Bai, Ruixue Jia and Jiaojiao Yang, study elite efforts in war mobilization to suppress the Taiping Rebellion in 19th century China. The rebellion, that lasted 14 years (1850-1864) and briefly overlapped with the American Civil War, was one of the deadliest in human history killing at least 20 million. The paper studies recruitment and mobilization for the Hunan army that under the leadership of a scholar-general Zeng Guofan finally managed to suppress the rebellion. Using records on China’s Civil Service Exam system — the primary recruitment channel for the country’s bureaucrats — as well as records of marriages, kinship and friendship networks the paper shows that the General leveraged his personal networks to recruit soldiers for the war effort. Counties with more dense connections to Zeng experienced more casualties in the war.

Importantly, these same counties also saw the rise of new provincial and national-level elites. The rise of these new regional elites likely led to the weakening of the Chinese state, and the eventual fall of the Qing dynasty. The findings of the paper shows how the interconnectedness between war-making and elite trajectories has implications for state capacity. In a notable twist to Charles Tilly’s famous aphorism – war made the state, and the state made war — they show that elites made war, and war made elites.

In the second paper, Peng Peng studies 17th century China and argues that rulers strategically use patronage appointments to secure not just loyalty but to gain trusted bureaucrats in times of conflict. She shows that the Imperial court was more likely to make patronage appointments during times of internal and external crises in order to mitigate risk. Conversely, the court relied on meritocratically chosen bureaucrats during time of peace. In this way, wars weakened the meritocratic state.

Beyond distributional or territorial conflicts, Yusuf Magiya in a new paper argues that ethnic diversity weakens state capacity because diversity makes it harder for the state to collect accurate information about its residents. This mechanism hinges on one specific type of diversity: language. Using a dataset on provincial taxation spanning multiple decades in the Ottoman Empire, he shows that during wars, more ethnically diverse places collected less taxes than homogenous places. Also, places with majority Turks collected more taxes than other places. Crucially he finds evidence of his mechanism by examining the expense to revenue ratio that speaks to the efficiency of tax collection in less diverse contexts.

Collectively these findings show how studying the inputs to state capacity – bureaucratic presence, informational quality, civil service procedures – have enabled a shift in the field. From macro-historical processes a la churning wheels of history to studying the micro — the role of elite motivations, ground level economic/political shocks and social conflict in endogenously shaping different types of capacity at critical moments.