The Myth of Meritocracy: How Exams Helped Build an Empire

By Peng Peng (Washington University in St. Louis)

Imperial China was a meritocracy. That’s the story we’ve long been told—and one that has shaped how generations have understood the Chinese state. For over a thousand years, aspiring officials sat for grueling, multi-level exams, with the top scorers earning posts in the imperial bureaucracy. In a world where birth usually determined one’s future, this system seemed radically modern: government by talent, not by bloodline.

It had profound implications. While European monarchs often contended with aristocratic families and parliaments, imperial China centralized power through a professional bureaucratic class—one that was selected not for its lineage, but for its education. Scholars have argued that this system allowed China to build a strong, centralized state without the need for hereditary elites or representative institutions.

The idea resonated far beyond China’s borders. Enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire praised the Chinese meritocracy. In the 19th century, British reformers adopted exam-based recruitment for the Indian Civil Service and later the British civil service. Even today, defenders of Chinese technocracy point to this long tradition to argue that meritocracy—not democracy—has always been the Chinese way.

But the reality is more complicated.

In my recently published article, I revisit this powerful narrative using a new dataset that covers every known prefect who served during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). What I find disrupts the standard story. The exams were real, and they mattered—but they weren’t the whole story. In fact, they weren’t even the main story.

Imperial China, it turns out, didn’t rely on a single, uniform pathway to power. It had a flexible and adaptive elite selection system, in which meritocracy was only one part of a broader toolkit. More than anything, I argue, the exam system served as a tool for projecting the ideational power of the state: it didn’t just select officials—it shaped how they thought.

Meritocracy Wasn’t the Whole Picture

To get a clearer view of how Qing China actually staffed its bureaucracy, I built a new dataset using a trove of overlooked historical records: local gazetteers. These encyclopedic volumes, compiled across the empire, contain biographical information on officials, including how they entered office.

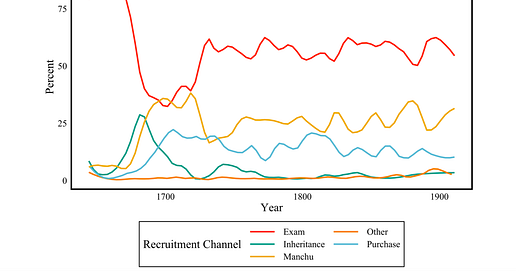

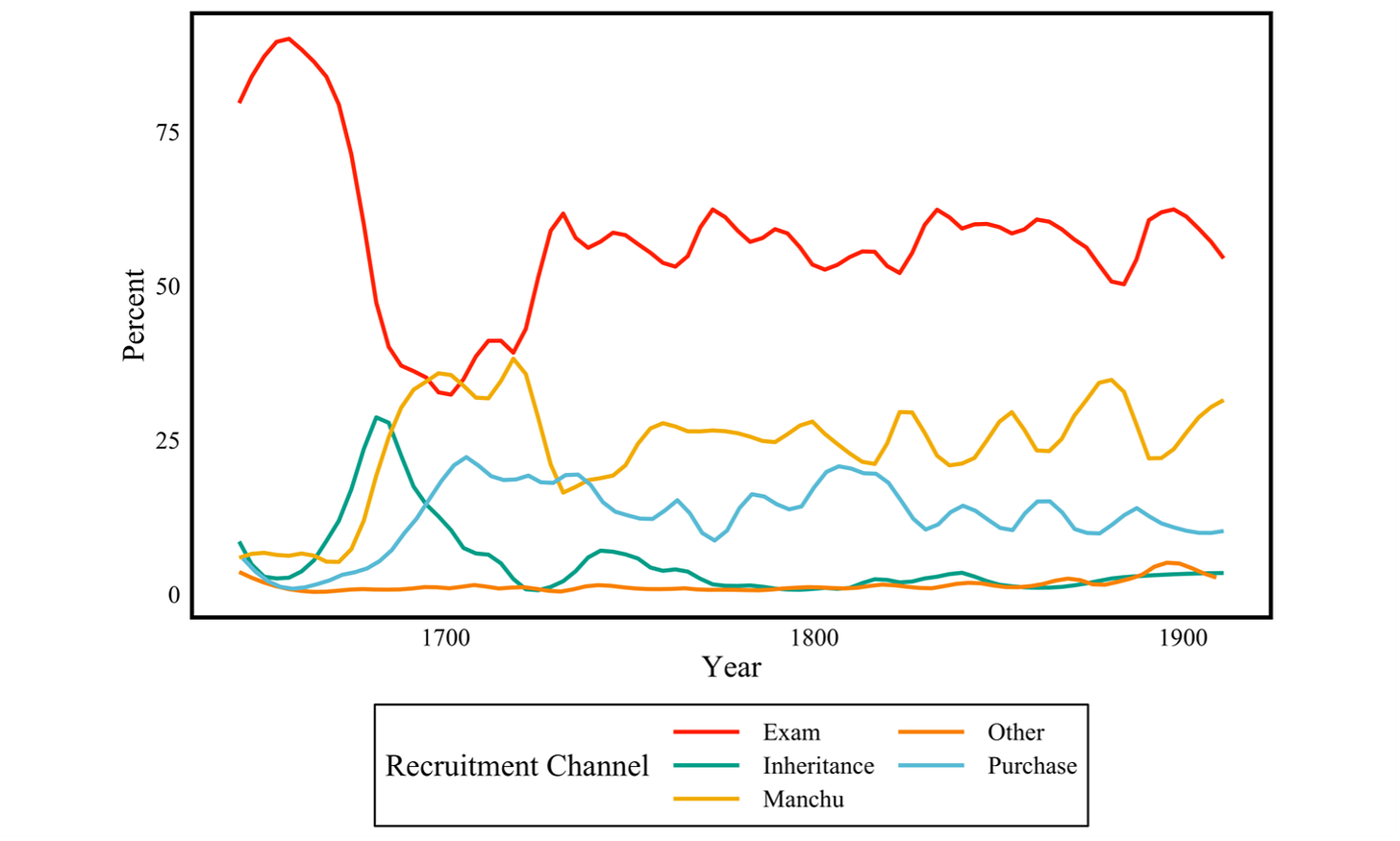

The results reveal a more complex picture than the traditional meritocracy narrative suggests. Out of 9,380 prefects who served under the Qing dynasty, only 57% came through the civil service exam system. The rest followed very different paths.

Roughly 13% bought their way into office by making “contributions” to the state—cash, livestock, grain, and military supplies such as warships and camels—in exchange for academic credentials. Another 4% inherited eligibility from their fathers, thanks to a policy that awarded degrees to the sons of deceased or high-ranking officials. A small group—about 2%—got in through ad hoc channels like battlefield promotions or personal recommendations. Then there were the 23% who were Manchus. As the ruling ethnic group of the dynasty, Manchus were allowed to bypass the standard exam system entirely. They often entered the bureaucracy through parallel institutions or separate military-based evaluations.

In other words, nearly half of Qing prefects were selected through non-meritocratic means—through wealth, bloodline, privilege, or ethnic status.

Figure 1 below shows the breakdown of these recruitment channels over time. While the exam system looms large in how we remember Chinese bureaucracy, the historical record tells a more fragmented—and more political—story.

Figure 1: Composition of Qing Prefectural Government Over Time

Then Why Meritocracy?

So if there were so many other pathways to power—purchase, inheritance, favoritism—why did emperors still rely so heavily on the exams? The answer is simple but powerful: the exams didn’t just determine who governed—they shaped how they thought. They created a bureaucracy that was not only educated, but culturally and ideologically unified.

This is the real genius of the system. Faced with the impossible task of monitoring officials across a vast and diverse empire, Chinese rulers turned to a subtler form of control: education as indoctrination.

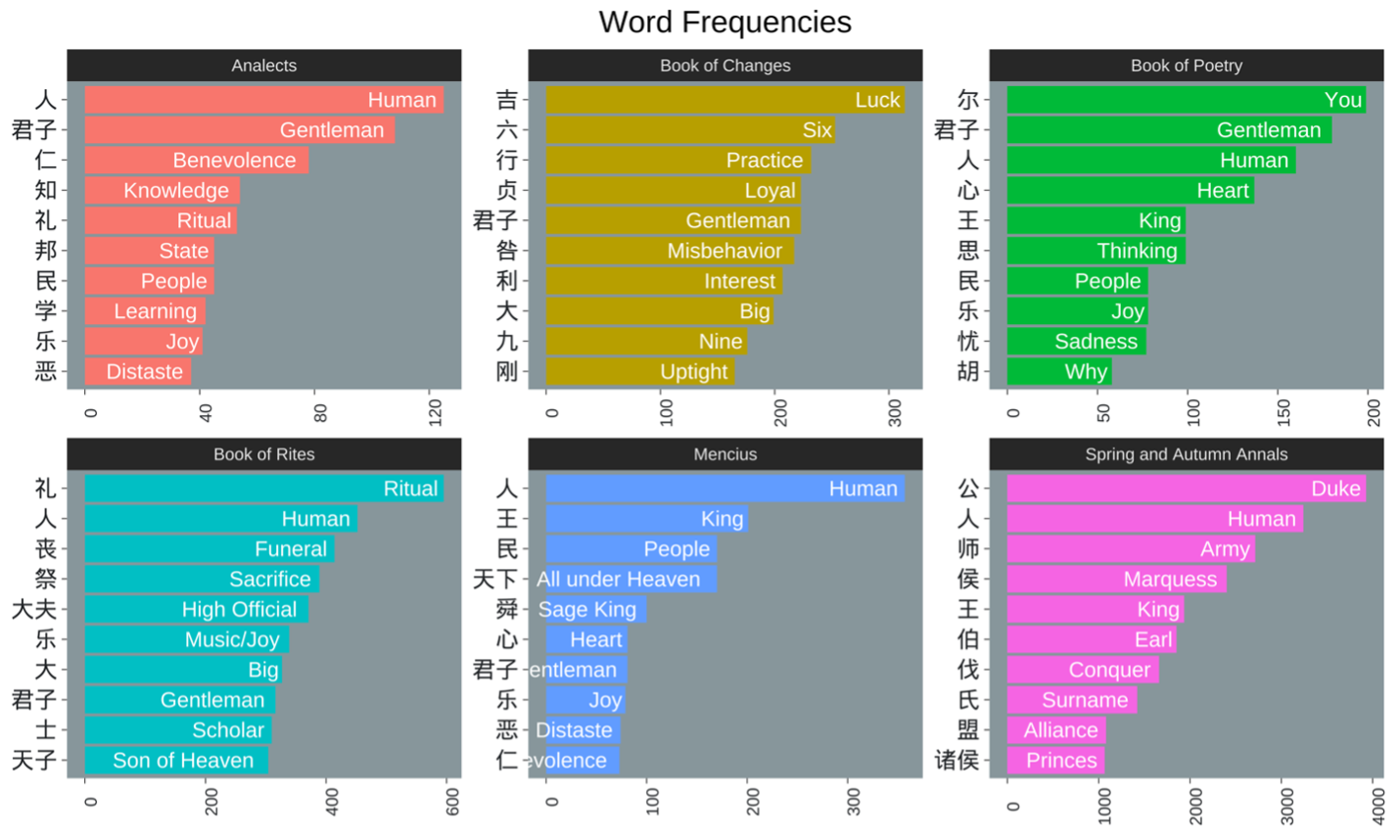

The exams didn’t test practical knowledge. Success hinged on a deep familiarity with the Confucian classics—texts like the Analects, Mencius, and the Book of Rites. Candidates had to memorize them, interpret them, and write stylized essays demonstrating not analytical skill, but moral and ideological alignment.

These texts centered on human relationships and ethical behavior (Figure 2). They emphasized hierarchy, filial piety, ritual propriety, and loyalty to superiors. They were not designed to train state-builders, but to mold subjects. In my text analysis of the exam canon, characters like “human” (人), “heaven” (天), and “virtue” (德) appear far more frequently than anything related to governance or administration. The message was clear: to serve the state, you first had to adopt its moral worldview.

And this wasn’t just signaling or surface-level propaganda in the modern sense. It was deep cultural training, much like the role the Catholic Church played in shaping medieval European elites. Just as the Church used scripture, ritual, and Latin education to create a shared clerical identity across fragmented kingdoms, the Qing state used Confucian education to create a loyal, ideologically unified bureaucracy.

This is what I call ideational power. Instead of relying on force or money, the state cultivated a ruling class that believed in its mission. The exam system created officials who didn’t just follow the rules—they internalized them. The result was a culturally coherent bureaucracy, bound together by shared texts, values, and habits of thought.

In short, the exam system wasn’t just a recruitment mechanism—it was an instrument of political reproduction. It ensured that each generation of elites would not only be literate, but loyal. They governed not just in the emperor’s name, but in his image.

Figure 2: Word Frequency of Confucian Books

Rethinking Meritocracy

So what does this all tell us about meritocracy—beyond imperial China?

We live in a world that has long celebrated the ideal of meritocracy. Over the past few decades, millions of families have poured time, money, and hope into education, believing that hard work and talent—not privilege—should determine success. Even amid growing critiques of the system—from concerns about inequality to the so-called “meritocratic trap”—the ideal still holds powerful sway.

But China’s imperial system offers a sobering lens on this belief. The Imperial China exam system was meritocratic in form but not always in substance. It relied on a supposedly neutral selection device—exams—but in practice, what counted as “merit” was highly specific: memorization of Confucian moral texts that promoted loyalty and conformity. It wasn’t about technical skill or innovative thinking. It was about producing a certain kind of person.

This raises important questions for how we conceptualize modern meritocracies before we even do empirical analyses. First: What is the content of the selection process? Is selection testing broad abilities—or reinforcing a narrow vision of worth? Second, are there any hidden pathways to power? And third: Who has access to the training needed to succeed? Meritocracy can easily mask deep inequalities in educational resources, cultural capital, socioeconomic backgrounds, and ideological gatekeeping.

In short, the Chinese case reminds us that meritocracy is never just about how people are selected. It’s about what defines merit, what purpose the system serves, and what kinds of individuals it is designed to produce.

Author:

Peng Peng is currently an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science and Global Studies at Washington University in St. Louis. Previously, she was a postdoctoral research associate at Washington University in St. Louis (August 2024 to Jan 2025) and the Macmillan Center, Yale University (July 2022 – June 2024). She received her doctoral degree from the Department of Political Science at Duke University in December 2022. Before that, she completed a dual master's program in International Affairs from the Paris School of International Affairs of Sciences Po Paris and the School of International Relations of Peking University, and she earned her BA from Beijing Foreign Studies University. She studies state-building and nation-building, focusing on the role of political elites in shaping state development and national identity.

Anyone trying to wrap their heads around concepts like "elite overproduction," credentialism, the decline of competence, and distrust in institutions needs to read this essay.

Good article here.

Reading classic Chinese historical novels like Three Kingdoms and Outlaws of the Marsh, a recurrent trope is that of the man who fails the imperial exam and becomes a bandit or warlord. There were many who wanted to be a part of the state but were locked out of the system by their own inability to pass the test, or those like Zhang Jue (who led the Yellow Turban Rebellion) who passed at the county level but who was denied further promotion. To the extent that this was a historical phenomenom and not just a literary conceit (e.g. Huang Chao and Hong Xiuquan both failed the test hundreds of years apart and led rebellions), it might be an argument against the idea that the examination system produced stability.