The Making of America: migration in colonial times

By Leticia Arroyo-Abad (CUNY) and Jose-Antonio Espin-Sanchez (Yale)

1492 marked an inflection point in the history of humanity. The initial voyage by infamous Christopher Columbus kickstarted one of the most important — if not the most important — migration in history.

The profound political, economic, and social changes that followed have inspired thousands upon thousands of studies. We understand much more about the demographic impact of conquest and colonization on the American indigenous populations. We have learned much about the forced migration of millions of Africans.[1]

But, perhaps surprisingly, we lack knowledge about a key group in this process: the European migrants. This is where we come in. Funded by the National Science Foundation and the Economic Growth Center at Yale University, we are working on a project to shed light on the European migrants to Spanish America. Starting with migrant zero, Christopher Columbus, we have gathered microdata on the hundreds of thousands of Europeans that ventured to the “New World.”

We want to share our intellectual adventure and some insights we have learned so far.

Inspiration and perspiration

Many scholars (and others) have blamed Latin America’s disappointing economic performance since independence to the traumatic colonial origins (Engerman and Sokoloff 1997, Acemoglu et al. 2001). We talk about “bad” colonial institutions, unfavorable factor endowments, and risky production profiles. It is of course undeniable that the Spanish colonization of the Americas was shaped by the available resources. But was the impact of the interaction between the colonizers, the colonized, and the enslaved really so clear cut? While we have an extensive scholarship on selected locations within the Spanish Empire, we lack a general knowledge about the origins and characteristics of the colonizers. Our lack of knowledge about the colonial migration contrasts with our wealth of data regarding the later age of mass migration (1860-1920). This vital episode in history lacks a systematic analysis of the migrant flows that changed the world.

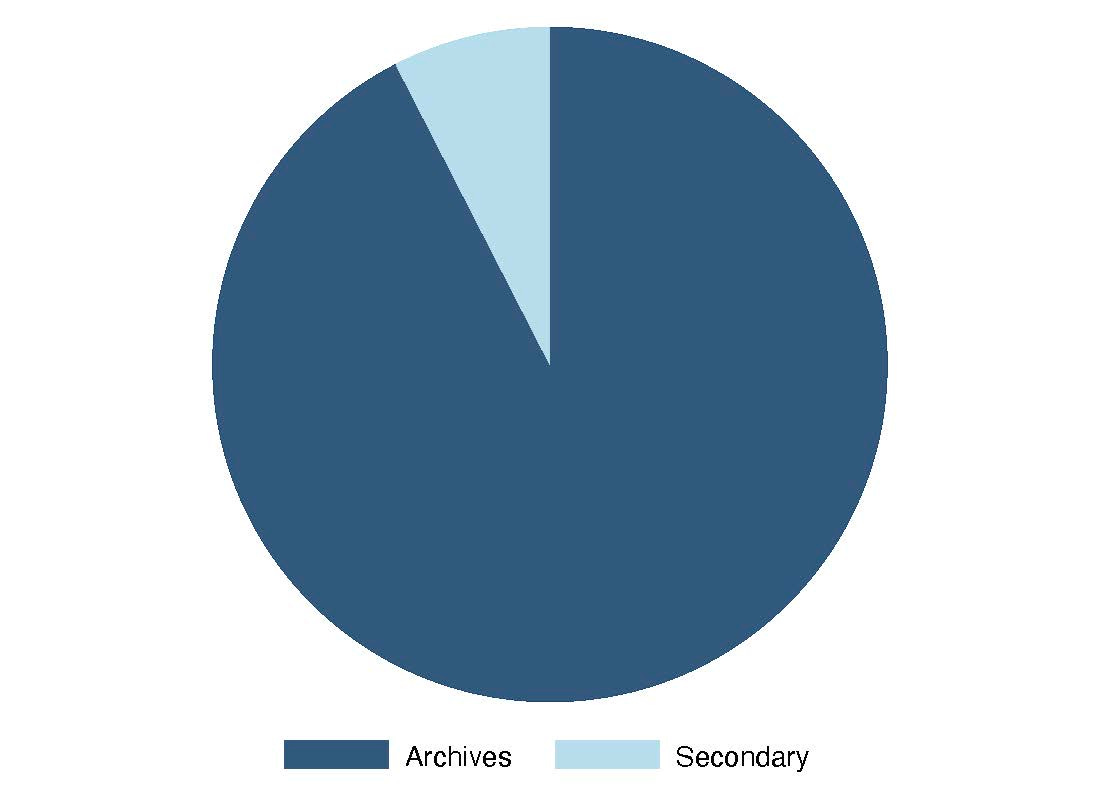

Our project is mainly based on the transcriptions of thousands upon thousands of unpublished records housed at the Archivo General de Indias (AGI) in Sevilla, Spain. We have assembled the first database of individual migrant records with a rich set of characteristics including sex, occupation, origin, destination, and year of departure. For the early period, 1492 to 1540, we have transcribed all the individual records from Boyd-Bowman (1964), Boyd-Bowman (1968), and Archivo General de Indias (1940). Due to the nature of the record-keeping practices in the early period and unfortunate fires at the AGI, we also consulted secondary sources to include the four Columbian voyages (1492, 1493, 1498, and 1502), the Ovando expedition, and other esoteric sources like contracts of carriage housed at the archive of notary records in Sevilla. Over 90% of all our observations come from primary sources: licenses, ship manifests, and contracts (see Figure 1).

Other scholars have tackled this topic. Boyd-Bowman (1964, 1968), using secondary sources, put together thousands of records of voluntary migrants throughout the first century of conquest and colonization. His magnum opus, Indice Geobiográfico de Cuarenta Mil Pobladores Españoles de América en el Siglo XVI, is the first attempt to quantify the migration flows to Spanish America. Marques Macías (1995) resumes this study for the late colonial period (1765-1824). We also have rough back-of-the-envelope estimates by Engerman (1999), Eltis (1989), and Morner (1975). All these estimates, however, fall short of a detailed picture of migration flows that lasted over three centuries of Spanish rule (1492-1820s).

Translating sources

Our project heavily relies on the state apparatus created to regulate migration to the Americas. The Spanish Crown highly regulated migration to have the “right” kind of people settled in the newly-acquired territories. This translated to Catholic, qualified, and from the unified kingdoms of Castilla and Aragon.

In order to travel, a prospective migrant needed to apply for a “visa.” This application attested his or her purity of blood (at two generations Catholic), good character (no outstanding debts or criminal history), and documentation on origin (marital status, noble status, and other family history). These “visa” applications are one of our main sources for our project, known as licencias, licenses.

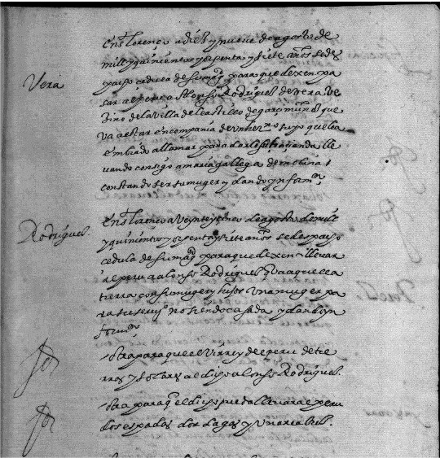

These licenses provide a wealth of information on individual migrants and their companions. Let’s explore one of them. In 1587, Alonso Rodríguez de Vera (see Figure 2) applied to go to Peru to join his brother on his hacienda. His application for travel includes his wife, children, and a female servant. He also took the opportunity to request lands at destination and to request authorization to bring along weapons (two swords, two daggers, and an arquebus).

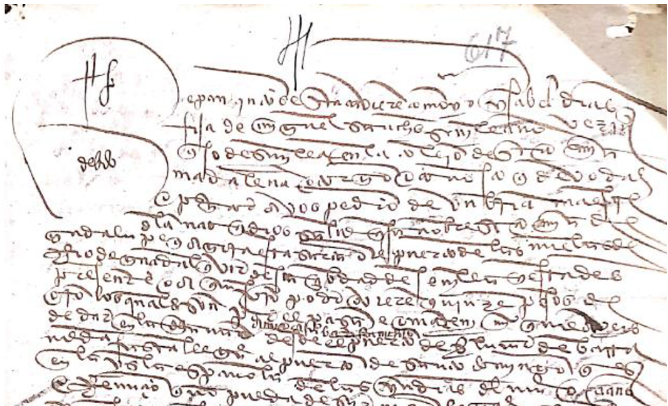

Once the “visa” was approved, the migrant had to buy a “ticket.” Housed in a different archive, also in Sevilla, we have found and transcribed thousands of contracts of carriage signed between migrants and shipowners. They provide very useful information. In the case of Isabel Díaz, the contract of carriage between the Sevillian passenger and Pedro de Umbría –first officer of the ship Santa María de Guadalupe—stipulated payment of 15 gold pesos for travel to the port of Santo Domingo (in the present-day Dominican Republic). From this document we also learned that Isabel was illiterate as Pedro de Oviedo signed it on her behalf (see Figure 3).

Finally, the migrant had to board the ship. That is another of our sources: the ship manifests –known as asientos. These documents have similar information as the licenses but in an abridged form and listed by ship departed from Sevilla. All these sources allow us to build a fairly detailed picture of voluntary migrants traveling to Spanish America.

Trends

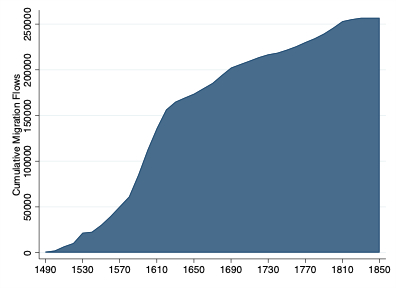

This labor of love allows us to assess the size of the migrant flows from Spain to the Americas for the entire colonial period. We can attest that over 250 thousand free Europeans left their homeland to try their luck in the New World (see Figure 4). The first four decades we observe migrants trickling in, moving to an ever-expanding menu of destinations. The flows accelerate for a century to then increase but at a slower pace for the remainder of colonial rule.

Regarding origin, as it is well-known, the initial conquest was mostly a Castilian phenomenon. Although, there were no restrictions on travel from other Spanish kingdoms, network effects were strong, and the early migrants were mostly Castilian. Migrants from other regions were much more likely to be merchants. Early migrants were mostly males, and mixed with the locals throughout the 16th century. This pattern changed, starting in the mid 17th century, the typical migrant travelled with his entire household increasing the female migrant share to 50%. We see a similar pattern for the clergy, with very few friars crossing the pond after 1650.

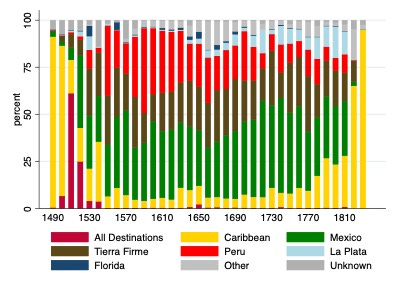

As for destinations, we discovered that following the footsteps of the conquistadors, the first twenty thousand migrants moved first to the Caribbean, then to Tierra Firme (modern-day Central America + Colombia + Venezuela) to then arrive to what would become the pillars of the Spanish empire: Mexico and Peru. But that pattern did not last. Over the entire period, the bulk of migrants chose as their main destination Mexico and Peru: almost 60% of all migrants declared these two destinations (see Figure 5).

Our estimates are far below the existing upper bound estimate of 746,000 people by the late colonial period. Granted, Engerman’s figures are based on Eltis’s own estimates obtained from population data of the Americas and Morner’s own ship size estimations. We cannot claim that our detailed research will capture every single European that ventured to Spanish America. We are, however, confident that we are offering a trustworthy lower bound estimate. To assess the robustness of our estimates, we replicated Morner’s numbers (based on Chaunu’s accounting). We refined these estimates by removing selected ships categories that were unlikely to carry passengers: slave ships and those carrying mercury from the mines in Almadén in Spain to Mexico. In addition, we adjusted ship sizes using recent studies which found that while the nominal tonelada castellana was getting bigger, the actual ship tonnage remained the same. This resulted in tonnage nominal inflation of 60% by 1620 and coincides exactly with Morner’s inflated estimates of likely migrants.

Searching for answers

Our project has opened more and more questions as we moved along. We have a pipeline of projects with different co-authors to exploit this rich dataset.

We have started with the early period, the first waves of migration. We look at the first movers and settlers, starting with Christopher Columbus and ending with a decade after the conquest of Peru. In “Gambling for America,” joint with Yannay Spitzer and Ariell Zimran, we characterize the early migration flows to find that a clear pattern emerges. Networks of origin develop quickly with one-third of all migrants coming from two provinces –Sevilla and Badajoz. These migrants did not have much knowledge about the destinations per se. Rather, they headed out to new destinations almost randomly as the frontier opened up new areas for settlement.

With Desiree Desierto, we are looking at labor coercion practices in Spanish America. As the conditions on the ground varied considerably throughout the empire, different equilibria emerged leading to a spectrum of extraction. With Noel Maurer and Miguel Angel Navarro, we are starting a paper studying forced migration to the New World. Using a companion dataset on enslaved migrants, we are tracking these flows throughout colonial times. We are also working on a big-picture article taking into account different inflows of migrants, enslaved and voluntary, and the demographic trends that emerged after the Conquest. In addition, the imperial expansion also had effects in the motherland, in terms of population movements, we are interested in analyzing how emigration to the Americas affected demographic dynamics within Spain.

Slowly but surely, we are tackling important topics about migration in colonial times. We are populating our project website as we go along, please check it out: Bridging the Atlantic: Migrations & their Legacies.

So stay tuned! And if you have a brilliant idea for collaboration, please do reach out.

References

Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson. “The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation.” American Economic Review 91, no. 5 (2001): 1369-1401.

Boyd-Bowman, P. (1964). Indice Geobiográfico de Cuarenta Mil Pobladores Españoles de América en el Siglo XVI, Tomo I, 1493-1519. Bogotá: Instituto Caro y Cuervo.

Boyd-Bowman, P. (1968). Indice Geobiográfico de Cuarenta Mil Pobladores Españoles de América en el Siglo XVI, Tomo II, 1520-1539. Mexico: Editorial Jus. Mexico.

Eltis, David. Coerced and free migration: Global perspectives. Stanford University Press, 2002.

Engerman, Stanley, and Kenneth Sokoloff. “Factor Endowments, Institutions and Differential Paths of Growth among the New World Economies,” in Stephen Haber, ed., How Latin America Fell Behind, Stanford: Stanford University Press." (1997).

Mörner, M. (1975). La emigración española al nuevo mundo antes de 1810. un informe del estado de la investigación. Anuario de estudios americanos 32, 43 131.

[1] Thanks are particularly due to the impressive scholarly collaboration in Slave Voyages.

From roughly 1590 to 1630, this seems to have been the period when immigration was at its highest point. Politically, I wonder if the failure of the Spanish Armada in 1588 accelerated this trend. What were the motivations of the immigrants? Was the Spanish Empire in 1590 in decline or experiencing elite overproduction?