The arm of history is long, but not always strong: The effects of labor coercion in colonial and postcolonial Peru

Our project on the effects of forced labor in colonial Peru began years ago, Leticia was still a graduate student. The motivation was threefold. First, how did the Spanish pacify, control, and extract resources from their newfound empire? Forced labor played a prominent role in that story, but we felt its political economy was still incompletely understood. Second, how did forced labor shape the colonial economy (and viceversa)? That is, relative to reasonable counterfactuals, did the institutions imposed by the Spanish have measurable effects on economic growth and activity? Lest you think the answer is obvious, let us point out that wage labor did not exist before the Spanish arrived and that there are many cases in history of labor coercive institutions that were neither binding nor transformative. Finally, why did forced labor disappear by the end of the colonial era? Peru had no victorious civil war or glorious revolution or foreign liberation to stamp it out. So why did it fade away?

We were not interested in whether Peru’s colonial forced labor institutions still reverberated today. That is not, of course, because the question is not interesting. It is because the question did not seem particularly relevant. Why would we expect institutions that collapsed under their own weight before 1800 to still have measurable effects in 2010?

We examined both the mita, which drafted adult males to work in mines and public works, and the localized encomienda, which empowered Spanish settlers to force locals to work for them. We found that Peruvian communities subjected to forced labor experienced greater local population decline at the beginning of the colonial era, but the decline reversed after a century and they rebounded before independence.

It wasn’t until after 2010 that we began presenting the results — by then, Melissa Dell’s influential paper on the long-term effects of the mining mita to the silver mines in Potosí (Bolivia) had already been published in Econometrica. She found that the areas inside a putative mita boundary were poorer and less developed today than places outside the boundary. Without fail, every time we presented our paper, the audience would ask, “what about Dell’s paper?” That prompted us — more accurately, it forced us — to examine post-colonial outcomes. Given our colonial results, we were not surprised to find no long-term impact. (We explain below why our findings differed from Dell’s 2010 paper.)

This difference with Dell, however, created a challenge for us. Melissa Dell had established herself as a leading figure in economics, for understandable reasons. We had a paper suggesting that a key finding in her seminal work needed reconsideration. We sent her the paper and we received very useful comments, which we incorporated into our revisions. Obviously, she disagreed with our interpretations, but our exchanges were friendly and respectful.

Our first submission was to the American Economic Review, one of the leading Economics journals. The editor took the unusual step of sending it directly to Melissa Dell for “pre-review.” She responded with some criticisms of our historical data. The editor did not consult a historian to assess the various sources.1 Instead, he advised us to resolve the disagreement ourselves as “matters can get very complicated and even contentious otherwise.”

Taking Dell’s comments into account, we rewrote the paper and submitted it to the Economic Journal. The editor sent it to three referees. One of them was Melissa Dell. She wrote a letter saying only that we already had her comments. That was odd, considering as we had explicitly incorporated or responded to those comments in the new text and submission letter. The paper was rejected.

So we sent it to the Journal of Economic Growth.[3] Because our findings contradicted an established paper, the editor put us up against the toughest associate editor we have ever encountered in our professional lives. It was one of the most grueling intellectual experiences imaginable. That said, the associate editor was scrupulously fair — if quite brutal — and the process ultimately strengthened our paper. It emerged much improved. But we cannot say that the experience was anything approaching a normal review process for the social sciences.

Anyway, after that gauntlet, and many many years, this paper found a home. We think it has something interesting to say. Download it, read it, cite it!

The Shadow of History

Our paper examines a canonical case of forced labor: the encomienda and mita in colonial Peru. The encomienda granted individual Spanish colonizers the right to extract labor from indigenous peoples. The mita was a centralized forced draft designed to provide labor for mines and public works across much of what is now Peru and Bolivia. Both built on pre-Hispanic social structures and political institutions and required no small level of indigenous collaboration to function.

Armed with a dataset of 500 indigenous settlements scattered across modern-day Peru, we find that forced labor impacted the communities subjected to it — but the effects mostly dissipated before the end of the colonial period in 1811.2 In short, we found that while forced labor mattered, its effects did not persist.

Why did labor coercion fail to generate long-term geographically-bounded effects in Peru? The reason is that it decayed from within. Four forces eroded the mita and the encomienda throughout the colonial era.

First, the imperial government in Spain was not sanguine about the power of the encomenderos. The last thing they wanted was the rise of a colonial elite that could challenge their authority. They therefore limited and undercut the encomenderos any way that they could, to the point of provoking multiple rebellions and small-scale civil wars. Encomendero resistance slowed the imperial assault, but did not stop it. (Of course, this applied to the encomienda, but not the mita.) Eventually, the colonial state replaced the encomenderos with salaried officials called corregidores (literally, “co-rulers”) and government took on a more “modern” form.3

Second, more Spanish settlers arrived. As the economy grew, they wanted access to the labor locked up by the initial conquistadores via the encomienda and the colonial state via the mita. They politically mobilized to gain access to labor—and when that failed, they offered wages to encourage workers to move. In other words, they brought modern labor markets to Peru that further undercut the labor coercion system.4

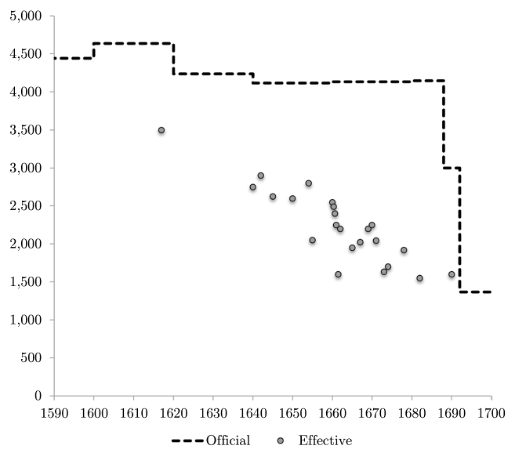

Third, both forced labor institutions relied on the cooperation of indigenous elites to provide the labor. The system relied on indigenous leaders to deliver labor. But those leaders had options. Some communities bought their way out, substituting silver for labor. Other communities reported suspiciously high numbers of female births, since females were exempt. Some sabotaged demands—the people of Jauja, for example, simply refused en masse to report for duty. And when all else failed, they resisted — sometimes violently. As a result the actual numbers of draftees declined quite radically, even after the population stabilized (see figure below).

Finally, migration: migrants who moved to a new community were subject to neither service, tribute, nor labor drafts of any type, which under Spanish law and custom applied only to the natives of the community. In the words of historian Jeffrey Cole: “Indian migration was the mita’s main legacy.” Migration blurred the lines. Treated and untreated areas mixed. Over time, the entire geographic logic of the system broke down.

By the time Peru’s coercive labor institutions were formally abolished in 1721 (the encomienda) and 1812 (the mita) respectively, they were practically dead letters.

The data

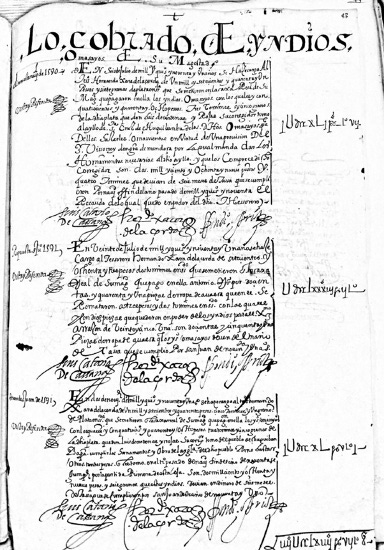

So … much … data. We want to go on about our sources in great depth, because it took years of work in darkened archives reading documents like this:

Our unit of analysis was the reducción, or settlement. Our sample came close to the universe of observations: the Visita General of 1570-75 identified 585 indigenous settlements across the territory comprising modern-day Peru. We started in the 1570s at the tail-end of the Spanish conquest and moved forward through the colonial period for population. We then moved into the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries to capture a range of postcolonial outcomes.

We found that the local population of “treated” communities fell compared to untreated communities during the first century of forced labor, but it then rebounded. This result held when we separated out the encomienda and the mita. As endogeneity is always a threat, we employed an instrumental variable approach and tested for selection on unobservable variables. We then tested for postcolonial outcomes, looking at population, landownership, literacy, road density, and night-time luminosity (as a measure of economic activity). We found no effects in the long run.

The difference with Dell

Why did our results differ from Melissa Dell? There are three primary differences. First, we examined multiple types of forced labor while Dell examined mainly the Potosí mining mita.

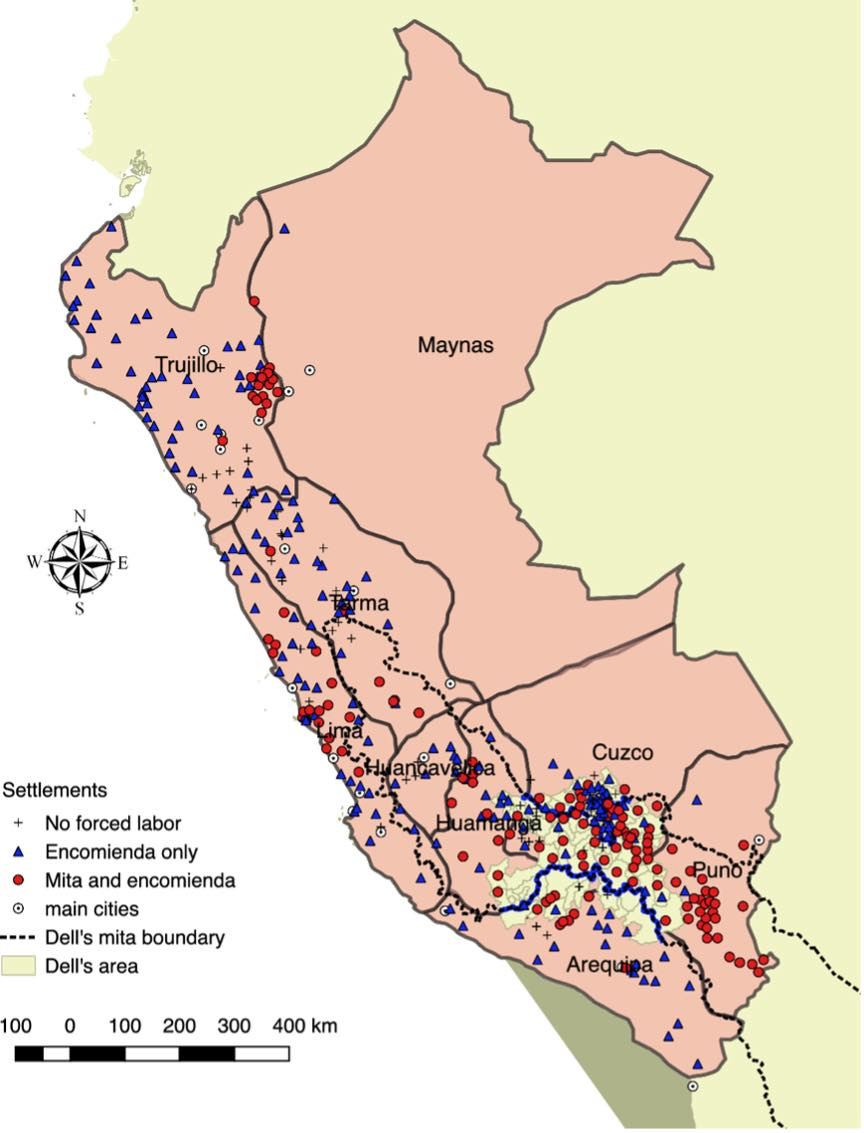

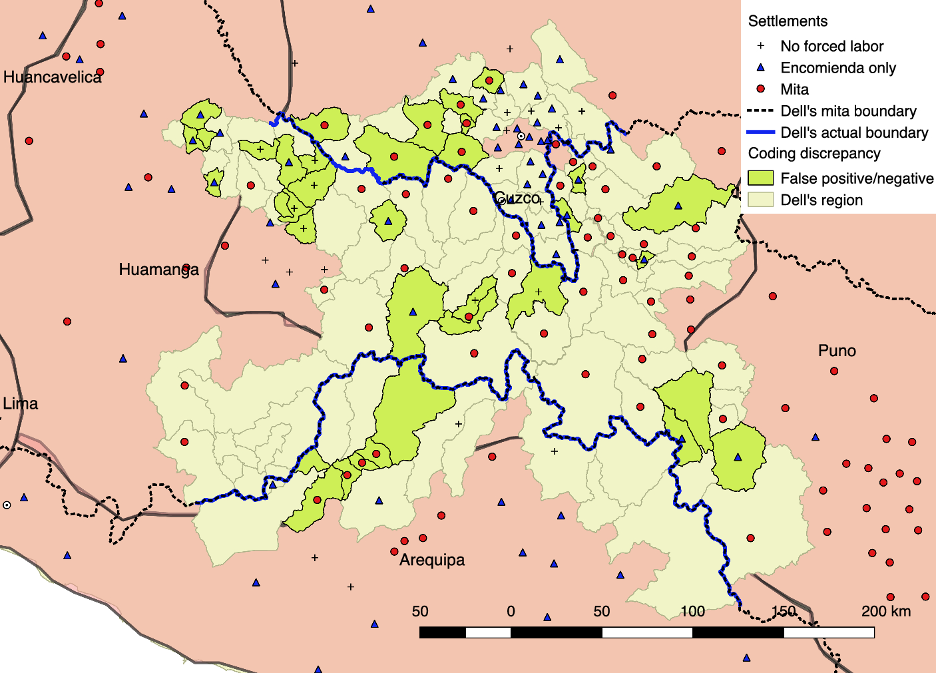

Second, our study area covered all of modern Peru, as opposed to a smaller section in southern Peru (see the beige area in the map below). We are not clear on why she limited her study to that area, although she says it was due to RDD balance sample requirements.

Finally, and most importantly, we used settlement data that allowed us to map colonial communities onto modern districts. Dell, on the other hand, identified colonial provinces as subject to the mita and then mapped those provinces onto modern-day jurisdictions. She identified the geographic scope of the mita from two main sources: an 18th-century official end-of-term report of Viceroy Manuel de Amat y Juniet (1761-1776) and a 1984 monograph by Thierry Saignes, from which she added the province of Paucarcolla. She then mapped colonial provinces onto modern-day districts using a geographic compendium from the late colonial period and a 19th-century source on Peruvian political boundaries. She coded all modern districts within a colonial province subject to the mita as subject to forced labor.

Unfortunately, mapping colonial provinces onto modern jurisdictions is not at all straightforward. In fact, it may not be possible. Provincial boundaries in colonial Peru were remarkably unstable. Their geographic extension did not correspond to our modern notion of territorial borders. Rather, borders were determined by the area occupied by members of indigenous communities at any given moment. One way to represent this phenomenon is to think of moving populations bringing their province with them, rather than crossing a fixed provincial boundary. For example, Saignes, one of Dell’s sources, eloquently warned: “A first point concerns the identification and exact demarcation of the ethnic groups of the Andes who sent mining contingents to Potosí: the ethnic unit (called ‘provinces’ or ‘nations’ in documents and which correspond to a señorío or to a moiety (mitad) do not always coincide with the administrative colonial units (corregimientos, ‘mita captaincies’), which leads to an endless number of problems of attribution and of determining where villages in different fiscal and mining jurisdictions belonged.”

In other words, boundaries were fuzzy. Here is a 1790s map of provincial boundaries.

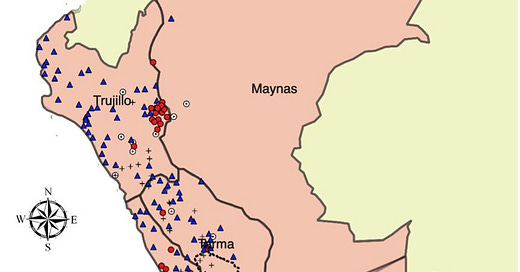

Our more granular data let us identify treated and untreated communities and map them onto modern equivalents. We found no discrete mita boundary. Rather, as the below map shows, we found a scattered mixture of treated and untreated communities. Dell’s area of analysis, therefore, included multiple false negatives and false positives.

In addition, the primary mechanism Dell proposed to explain persistence was hypothetical, as she herself stated. “I hypothesize that the long-term presence of large landowners provided a stable land tenure system that encouraged public goods provision.” The historical works cited in the paper, however, never claimed that the Spanish state discouraged hacienda formation in order to protect its claim on mita labor. Rather, her evidence was indirect, hinging on her finding that postcolonial public investment in education and roads was lower within her mita boundary. When we used her coding for the mita boundary, we replicated the finding on education but found that the result on roads was not robust to using a different cross-section.

We are unaware of any historians claiming that haciendas increased tenant well-being. That does not mean that the historical literature is correct, of course. Many bits of conventional wisdom have been overturned by a systematic analysis of the sources. But extraordinary claims require solid evidence. Mechanisms should not be assumed — they need to be shown to have actually operated using careful historical methods.

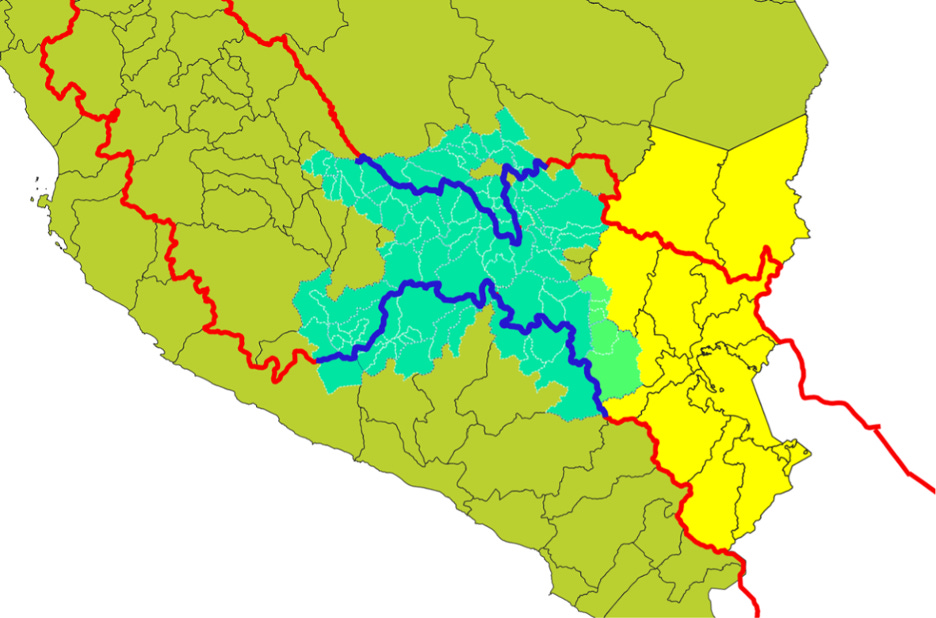

She suggested two other channels, both derived from property rights. The first was the putative presence of greater unrest and banditry within her mita boundary. The problem, however, was that none of the sources she used examined areas outside the postulated boundary. The below map illustrates the problem. The bluish area is her study area. The red and blue solid lines are the postulated mita boundary. The yellow area covers the sources for crime and unrest. The small green area, covering two provinces in the far east of the study area, is the only area of overlap—and both provinces are within the mita boundary. Since all observations are from inside, it is impossible to compare their levels of violence with areas outside the boundary.

The second additional channel she proposed was that the “good” effects of haciendas may have derived from a 1969-75 land redistribution that broke up the haciendas — which seems an ironic mechanism for a paper claiming that the effects of an institution persisted across centuries of war, revolution, urbanization, and industrialization. Why was that ironic? Well, General Juan Velasco and the Revolutionary Government of the Armed Forces took power in a 1968 coup d’état and began land reform the next year. Redistribution officially lasted until 1978, but Velasco fell to a 1975 counter-coup organized by conservatives grouped around his own prime minister. As a practical matter, then, most redistribution ceased in 1975. The conclusion would therefore be that six years of land reform can overturn 400 years of history. That does not say much for the staying power of forced labor’s legacy.5

One might speculate that forced labor had long-term impacts on Peru as a whole, without having any differential impacts across geographic areas within the country. For example, migrants did not need to leave communities with forced labor in order to escape its reach; they just had to move to another community. Such moves could have evenly depressed access to communal land across Peru. Similarly, mass migration might have strengthened elite control over the receiving communities — again without distinguishing between treated and untreated communities, since all would have received outside migrants. It is also possible that forced labor might have twisted colonial Peru’s political structure in lasting ways or somehow strengthened discriminatory norms against indigenous peoples, or between indigenous groups. This is akin to arguing that the existence of slavery in South Carolina altered institutions and norms in New York. Put that way, the argument is not at all implausible! But it will be extremely difficult to disentangle the effects of labor coercion — if any — from the broader Spanish imperial legacy. After all, national effects cannot be measured using subnational data. Testing the hypothesis that colonial forced labor conditioned independent Peru’s economic development will mean making cross-national comparisons using careful historical analysis.

Conclusion

Our contribution is not solely about Peru. Our findings also speak to a large persistence literature that sometimes loses sight of the fact that not all forms of persistence are the same. We lack a general theory of persistence that would predict ex ante which institutions will have effects that outlive their disappearance and which ones will not. We do, however, have general theories of economic change which are consistent with the fading effects that we find here.6

More broadly, historical knowledge is vital when analyzing long-term persistence. Without it, key institutional details can be missed and implausible mechanisms asserted. The Peruvian mita did not follow a fixed boundary. Nor was the mita de minas the only — or even the primary — form of forced labor. In addition, forced labor did not remain static. Negotiation, migration, and resistance all served to weaken labor coercion. The growth of economic opportunities in the urban centers further diminished the power of coercive institutions. The changing context meant that the Peruvian state lost whatever capacity it had — along with the will — to impose forced labor over unwilling populations. It also meant that the mechanisms by which forced labor impacted long-term development weakened over time. Forced labor collapsed endogenously as populations migrated, bought themselves out, and resisted violently. The encomienda disappeared, labor tribute became a head tax, and mitayos morphed into paid laborers. As a result, forced labor left behind little trace at the local level.

The long arm of history is real. But sometimes, it punches soft.

For all the postmodern turn in history, there are many good young scholars in the United States and Latin America who can evaluate historical arguments and vet data sources.

The number was actually 500. That is not an approximation.

For an excellent analysis of how this process played out in Mexico — and the unexpected problems it caused — see the work of Broadstreet’s own Emily Sellars with her co-author Francisco Garfias.

The settlers increased the “outside options” enjoyed by indigenous laborers, see Acemoglu and Wolitzky (2011)’s labor coercion theoretical framework.

Albertus et al. (2020) looked at Velasco’s land redistribution. They found that land reform reduced years of schooling and were less likely to move to the cities despite higher urban incomes. This result is not consistent with the hypothesized mechanism.

Oded Galor’s unified growth theory appears to us to be particularly relevant.

This is excellent work.

Such a great post, thank you! Glad to see that economists are becoming more rigorous and careful in their use of historical data.