Quantifying the Rise of Meritocracy: Keju and the Politics of Social Mobility in China’s Tang Dynasty

By Erik H. Wang

The imperial civil service examination in Chinese history, known as the Keju (科举), began sometime between the late 6th and early 7th centuries and continued until 1905. It can be generically described as a system that recruited officials for the imperial government through a standardized written examination on Confucian classics and literature, open to most adult males.

In recent years, there has been growing interest from political scientists and economists in this historical institution. The system allowed aspiring individuals to enter bureaucracy based on exam performance rather than family background or social status. This proto-meritocratic aspect could theoretically bolster autocratic stability by expanding the selectorate. Unlike hereditary recruitment systems, Keju afforded the ruler the opportunity to potentially draw from a much wider pool of candidates, thereby rendering incumbent government officials more easily replaceable. Consequently, Keju has emerged as a popular explanation within the institutionalist approach to political economy for the political divergence between imperial China and post-Roman Europe, especially regarding ruler power and the equality between upper elites and the rest of society.

Quantitative studies of the Keju are mostly confined to the second millennium, particularly from the 14th century onwards, due to data limitations. However, by that time, the institution had already reached maturity. What about the role of Keju in expanding political access and social mobility when the institution was still in its nascent stage? To answer this question one must examine the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE). It’s the first dynasty where Keju became institutionalized and the last dynasty where the so-called “medieval Chinese aristocrats” were still thought to be present in the government. What’s the role of Keju in political selection? Did the credential of merit via examination matter a lot or was it simply epiphenomenal?

In an article recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) Fangqi Wen, Michael Hout, and I address these questions using a rare data source: 3,640 tomb epitaphs of males in the Tang. Epitaphs in medieval China contained highly detailed descriptions of an individual’s career and family background, accompanied by stylized prose and poems. While “orthodox dynastic history” volumes exist for nearly every Chinese dynasty, these sources exhibit a strong “winner bias” problematic for studying social mobility, as they primarily contain biographies of extremely prominent government officials. Historians have long relied on excavated tomb epitaphs as the closest possible approximation to a roughly representative sample of medieval Chinese elites, covering both the successful and, more predominantly, those less noted in the political arena. The process of these epitaphs’ discovery in modern times is mostly detached from the high politics of the Tang era.

By analyzing tomb epitaphs only, we also contribute to a longstanding debate among historians on whether and how the medieval Chinese aristocracy declined during the Tang. Classic works argue that institutional changes such as the Keju led to a chronic decline of aristocrats’ career advantages in the Tang. On the other hand, since the 1970s, several historians have emphasized aristocratic persistence, pointing out that the proportion of high government office holders from aristocratic backgrounds remained similarly high across both earlier and later periods of the Tang. However, by drawing conclusion from Pr(Aristocrats | High Office) rather than, for example, Pr(High Office | Aristocrats) – Pr(High Office | non-Aristocrats), the “persistence school” essentially “selects on the dependent variable.” Moreover, given the complex interplay of sociopolitical factors, merely tabulating percentages is an inadequate method to quantify the extent of meritocracy and the fate of aristocracy.

One could largely mitigate these problems by conducting regression analyses in an epitaph-only sample. But it has never been done by historians. Even a recent study that advocates the advantage of epitaph sample nevertheless resorts to calculating the same conditional probability from data consisting predominantly of individuals in orthodox dynastic histories.

Our original dataset contains a wealth of granular information from these epitaphs that help us disentangle the value of Keju credential (i.e. having passed the exam) from various sociopolitical factors and examine whether the aristocracy declined or persisted. We coded whether an epitaphee had passed the Keju. We also coded the rank of the final office held by the epitaphee as a measure of their career outcome. As year and age of death are specified in most epitaphs, we are able to quantify the changing importance of Keju as an institution over almost 300 years by tracking how the predictive power of Keju credential for career outcomes varied across birth cohorts.

Epitaphs allow us to decompose “aristocracy” into two dimensions. One is the power of the immediate ancestors. We measure it by the ranks of the highest offices held by the person’s father and grandfather. This is a “normal” dimension not unique to medieval China but widely considered as important in most parts of the world both historically and today. The second dimension is the pedigree of the bloodline itself, widely thought to be a distinguishing characteristic that separates medieval China from other periods of Chinese history.

Before the Tang, medieval aristocrats were identified by choronym-surname combinations. However, during the Tang, these markers lost their significance due to centuries of migration that changed elites’ places of origin from their self-claimed choronyms, coupled with the common practice of lower-born individuals fabricating choronyms to masquerade as aristocrats. Prominent “branches” within a choronym-surname combination became a new, more distinguishable marker of social status in the Tang. We therefore meticulously scrutinize each of the 3,640 epitaphs to ascertain whether the individual can be credibly traced to a prominent aristocratic branch from the early Tang period, using the epitaph’s descriptions and cross-referencing with various other sources.

Aristocratic pedigree is always understood by historians of medieval China as an important aspect of family background, in addition to the more “normal” dimension related to the father and grandfather. Understanding the decline of a “status elite” is also important for political scientists. Recent works on colonial India and the American South have shown that struggles for status dominance could have negative consequences for redistribution and state capacity.

Our data collection and analysis enable a “horse race” comparison among Keju, aristocratic pedigree, and the influence of immediate ancestors as predictors of career success, controlling for each other and various sociopolitical variables.

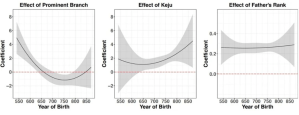

Our statistical analysis reveals that the importance of Keju grew steadily over the Tang Dynasty. Initially, passing the Kejushowed no correlation with an individual’s ultimate office rank. However, it began to predict career success for those whose political coming of age occurred in the 660s. The predictive power of Keju on career success continued to grow steadily from the 660s cohort, increasing consistently through to the end of the Tang Dynasty.

Contrasting with the rise of meritocracy is the decline of aristocracy. The predictive power of membership in a prominent aristocratic branch was initially quite strong but quickly declined over time. As with the Keju, the “inflection” seemed to have occurred for the cohort who reached adulthood in the 660s. Afterwards the association between ancestral prestige and career outcome was largely zero.

On the other hand, the more immediate dimension of family background was still consequential. The positively significant effect of father rank on son’s rank remained stable over time.

Could family background affect success in the Keju exam? A prevailing myth by the “persistence school” is that the overwhelming majority of Keju passers were aristocrats (whether by pedigree or by immediate ancestors’ ranking). This observation, again, selects on the dependent variable. The official government roster of Keju passers was never preserved. Throughout the second millennium, Chinese scholars had to compile severely incomplete “lists” from scattered mentions in the various surviving texts. Those included in these lists constitute only a fraction of the universe, and an even smaller fraction of those can be linked to an identifiable family background. When historians compute Pr(Aristocrats | Kejupasser), those outside the list and those inside the list but without detailed family info are omitted from the denominator, leading to upward bias in favor of aristocratic dominance as prestigious family backgrounds were more likely to be recorded in history. Other efforts to calculate this probability rely on using surnames and self-proclaimed choronyms from the incomplete passer lists to identify aristocracy, but as mentioned earlier, fabrication of choronyms was widespread in the Tang.

In our epitaph sample, only 38% of the exam passers originated from a prominent aristocratic branch, while just 26% had both a father and a grandfather who had served in mid-level bureaucratic positions or higher. In our regression analyses, neither aristocratic pedigree nor the office ranks of fathers or grandfathers predicted success in the Keju. The non-results for family background could be due to two reasons. First, our dataset is still an elite sample, consisting of males who could read, write, and afford epitaphs. Keju brought equality of opportunities to the broader elite, not necessarily the overall population.

Second, regarding father office ranks, further analyses conducted on my own reveal a nuanced picture. The original variable, categorized into 33 levels from low to high, was treated as a single continuous variable in our article. By dividing the father office ranks into four broad categories and including each as a separate variable in the regression, with “no office” as the baseline, I found that both higher and lower-ranked categories positively predicted Keju success compared to the baseline. However, the effects of these categories were not statistically different from each other. In other words, having a father in any government office aided your chances, but the rank of his office—high or low—did not significantly alter this advantage. This finding broadly aligns with historians’ analyses of the Tang’s Keju as a test where literary skills were heavily emphasized and answer sheets were not anonymized. This combination prompted candidates to circulate their essays and poems to officials before the actual test began, hoping that the reputation of their works would eventually reach the ears of the examiners. A “nudge” was necessary to ensure visibility, but ultimately, the merit of the writings mattered more.

Furthermore, our article also reveals that Keju exhibited what sociologists call an “equalizing” effect. While the right panel of the previous graph shows that father office ranks, in general, matter for son’s career success, our additional analysis finds that the effect of father office rank on son’s office rank is considerably less pronounced among those who succeeded in the exam. This result suggests that Keju provided a pathway for the lower elites to enter the bureaucracy and compete with the upper elites on a relatively level playing field.

All of this is not to say that Keju was an institutional panacea for political stability and social mobility. In a book project entitled “The Political Economy of China’s Imperial Examination System,” Clair Yang and I further examined how Keju had eventually become the game in town in Tang politics because of various external political developments that enhanced the elite’s incentives to participate in the exam. Importantly, the book project also takes a deeper look into the various actions undertaken by the Tang emperors to preserve the equalizing potential of Keju, including policies specifically designed to limit the advantages of high-ranking officials’ children in the exam. Keju was a tool, and it took effort to use it.

Overall, our study quantifies the rise of an institution over the longue durée. Through Keju, meritocracy displaced aristocracy as Chinese rulers expanded the “selectorate” and equalized access to political power.