On the Frontier Thesis

Economics and history Twitter are all abuzz about a HPE paper! That’s good, right? Even if there is occasionally discord between economic historians and historians? Oh, wait … the comments are something.

Fortunately, one of the paper’s authors, Martin Fiszbein, has a response to many of the comments. There have also been a few threads on it. I found this one interesting. I won’t repeat Fiszbein’s defense of the paper or the various arguments I have seen elsewhere. Indeed, it is not my goal to either defend or pile on this paper. I’m just here to give my opinion on it.

So, what is this paper that has attracted such attention from the historians of Twitter? It is Samuel Bazzi, Martin Fiszbein, and Mesay Gebresilasse’s forthcoming article in Econometrica: “Frontier Culture: The Roots and Persistence of ‘Rugged Individualism’ in the United States”. This article presents a test of the famous (if outdated) thesis by Frederick Jackson Turner that the American frontier fostered a culture of “rugged individualism”. By rugged individualism, they mean the combination of two traits: individualism and antipathy to government intervention.

How would you go about testing this hypothesis? The authors derive metrics for historic individualism (mainly the uniqueness of names, an increasingly common metric used in historical studies) and show that the longer a county was “exposed” to the frontier, the more “individualistic” its people are today. They have preferences against redistribution, vote Republican, don’t like government spending, don’t like taxes, and so on.

There is so much more to this paper. But that’s the gist of it.

I have read this paper and seen it presented before. I like it. I just re-read it. Before you ask questions about the analysis, please read it. I assure you that the authors have thought of your critique. It is a very well done piece of empirical economics.

First off, we should clear the air about something. This paper is most certainly not a defense of the Turner thesis. At best, Turner’s thesis glossed over genocide. At worst, it celebrated it. This is obviously not something to laud. But the authors do not do this. From the introduction: “Turner’s work has attracted immense attention and vast criticism. His narratives contain departures from the historical record, overblown statements, and ethnocentric biases. They paint an idealized portrait of frontiersmen and leave women and minorities out of the picture. The term “free land” appears often when, in fact, land was violently taken from Native Americans, and, in many areas, westward expansion was more about “conquest” than “settlement” (Limerick, 1988). These features of Turner’s work may explain why his influence, while still pervasive in history textbooks and classic narratives, has waned in recent historical research. Our study provides empirical support for some important elements of the Frontier thesis, but it is not a general assessment of Turner’s work nor an endorsement of its ideological overtones.”

This is not just window dressing. There really is nothing in this paper that celebrates the Turner thesis. In fact, there is only one aspect of the Turner thesis that is relevant for the authors’ empirical exercise. They use Turner’s definition of the frontier: “the line dividing settlements with population density of two or more per square mile from those with less.” This seems rather … benign.

In any case, the key argument of the frontier thesis is that the frontier helped shape American democracy. This is not at all what Bazzi, Fiszbein, and Gebresilasse’s paper is about. It is simply about how the American frontier helped shape a certain type of individualism.

That said, the authors do indeed frame their argument around Turner. I may be reading too deeply into it, but this may in part be the predilection of economists to tackle the “big questions” with new data. If their framing turns people off, that is a real shame. But, as someone who himself has worked on topics that rub people the wrong way despite not having read the work, I know that this is part of the price you pay for doing this type of work.

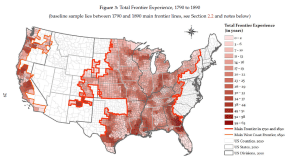

Let’s dig a bit more into how they define the frontier. It is not just places with very low population density. Rural Maine was not part of the frontier. They impose two criteria for a country to be considered part of the frontier in a given year: “(i) close proximity to the frontier line (100 kilometers in our baseline) so as to capture Turner’s notion of the “frontier belt”, and (ii) with population density below six people per square mile.” If the idea is to come up with a metric for a county being on the edge of what has been settled by (white) Americans, this seems reasonable. The figure below shows how the frontier evolved over time.

Using census data, the authors are able to assign counties to the frontier for every year (they focus on the period 1790-1890, when the U.S. was being “settled”). They then derive a metric called “Total Frontier Experience.” As the name sounds, it is just the number of years a county was on the frontier. The map below shows that this varied significantly across the U.S., concentrated mostly in the Midwest, South, and West Coast.

The idea put forth in the paper is that the longer the county was on the frontier, the more likely it is that a “rugged individualistic” culture emerged (more on that in a second). In other words, the darker red a county is in the above map, the more individualistic and anti-government attitudes the white population would have. Racial distinctions matter here. Blacks were not given the same opportunities and access to free/cheap land as whites. So we should not expect the same culture to have emerged among the black population living in these counties.

So, what is individualism? At a meta-level, we might think of it as anti-conformist. Or self-reliant. It places the individual above the social. In many ways, the economist’s trope homo economicus is the ideal individualist.

Rugged individualism can manifest itself in numerous ways, many of which are important for the social sciences. Rugged individualists tend to be anti-statist. They oppose redistribution and regulation. In their eyes, it should be the individual, not society or the government, that brings people up.

This is fine. But how do we test for individualism? The authors use an interesting metric which has recently been used by other studies to determine cultural assimilation: the uniqueness of names. On the one hand, this is probably not the ideal metric for individualism. We would rather know views on the government, self-determination, etc. But unless you have a time machine, those data do not exist. Name data do exist. And it is reasonable to think of unique names as an expression of individualism.

To the findings. I will do my best to lay out the findings as parsimoniously as possible. That means I am not going to discuss econometric techniques. Just know that the authors are seeking a causal relationship, not just correlations.

First off, the authors show a really strong connection between Total Frontier Experience and unique names. This is true in the short run (in the 19th century) and the longer run (in 1940). In other words, this connection persisted.

This is interesting, but it is far from the only finding. The authors also connect Total Frontier Experience to a host of contemporary cultural traits that get at the more “rugged” side of rugged individualism. For this we have survey data. They find that in counties with more frontier experience, people prefer cutting spending on the poor and cutting spending on welfare. The are more likely to believe that the government should not redistribute. Their preferences are also manifested in politics. Those counties have lower property tax rates and have a higher Republican vote share.

Was it something about the frontier that made people more individualistic? Or did more individualistic people simply move to the frontier? The authors show that it was both. In the language of economics, there was both selection to the frontier and a frontier effect.

This a very broad brush picture of the main findings. Yes, there are confounds. Yes, the authors have thought of them.

The paper does not definitively give us any causal mechanisms. Perhaps the Turner thesis is true. Perhaps the mythology created by the Turner thesis is what is driving all this. It could be something else. But that something else would have to square with the many findings the authors present. Likewise, if you think the Turner thesis is bogus (and perhaps it is), how do you account for their findings? Coming up with an alternative is not so easy in a paper as well-identified as this one.

What have we learned? Is this a question worth asking? Despite what some on Twitter would have us believe, this is in my opinion a really important paper. Yes, there are parts of Turner thesis that are problematic. Yes, there are parts that lack nuance. But does this mean we toss the whole thing out?

No! Especially the less problematic parts. Maybe it is an issue of framing. A different way to frame the paper is “there are some real, deep-seated cultural values that the Republican Party has been able to tap into … what are its roots?” Is it really crazy to think that places with a long history of being on the “frontier” (however defined) would enable these types of cultural values?

This seems like an immensely important question to me. It is by no means obvious that either the frontier actually enabled “individualism” or that it persisted. The authors show both of these are true.

This is not to say that social scientists should be able to take any old theory and hide behind the “I’m just testing for an empirical relation” defense. Some theories are truly odious and have no place in the social sciences. But the theory that Bazzi, Fiszbein, and Gebresilasse test is far from this. All they are doing is looking at one historical phenomenon that very well could have affected the culture of part of society. They then test whether that culture persisted. Given the pervasiveness of the attitudes they study, it is clearly important (in my mind, at least) to understand their roots.

In my last blog post, I wrote on culture in historical political economy. This paper is precisely the type of paper I had in mind. It shows us that culture matters. That is persists. How it persists. What its ramifications are. This is not easy to test empirically. Culture is “mushy”. It’s not something that lends itself to easy empirical tests. But we know it is important. The question is “how important?” This is tough to answer without some type of data, even if they are not perfect. That’s precisely what this paper does.