Intraparty Nomination Battles for Speaker

The U.S. House does not currently have an elected Speaker. One week ago, Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) was removed, as the motion to vacate (MTV) the speakership — offered by Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL) — was adopted. All voting Democrats and eight Republicans voted to vacate, the first time in House history the MTV has been successful. (Once before, in 1910, the MTV was tried and failed, as Speaker Joe Cannon (R-IL) survived.)

McCarthy had a difficult time as Speaker. It took 15 ballots to elect him in January 2023, the first time in more than a hundred years when a speakership election went beyond a single ballot. And his time in office was turbulent, as he faced significant GOP conflict over raising the debt ceiling and, more recently, funding the federal government going forward. His decision to send the Senate a “clean” bill to keep the government open through the middle of November drew the ire of some of the most extreme members in his conference. And this was the moment Gaetz was waiting for to offer the MTV. (One of the concessions McCarthy made to win the speakership was to accede to a rules change that would allow a single member to offer the MTV.)

Back in January, Charles Stewart III and I shared our thoughts on McCarthy’s travails in getting elected Speaker (here, here, and here), viewed both in the present and in historical context. A decade ago, we published a book, Fighting for the Speakership: The House and the Rise of Party Government.

Now, a week after the successful MTV vote, the speakership drama continues. The Republican conference is set to meet tomorrow (Wednesday) to hold a nomination election for Speaker. Two candidates have announced there candidacy: Majority Leader Steve Scalise (R-LA) and Judiciary Committee Chairman Jim Jordan (R-OH). But in the last couple of days, the possibility of McCarthy being reelected has increased. McCarthy initially said he would not be a candidate. But after the recent Hamas attack on Israel, McCarthy has played up his foreign policy experience and declared the importance of leadership stability in the House. He has not declared himself a candidate, but has remained coy about whether he would accept the job if offered. And, of course, some think the current Speaker Pro Tempore, Patrick McHenry (R-NC), would be a good Speaker and could be a dark horse candidate should a nomination deadlock ensue.

What will happen tomorrow? Will the Republicans be able to coordinate on a speaker nominee in their conference election? Or will it be deadlocked? And has this kind of thing happened before?

While Charles Stewart and I devoted considerably space in our book to all of the multi-ballot speakership floor elections that have occurred in U.S. history, we also noted that there have also been multi-ballot speakership *nomination* elections as well. Two are of particular interest:

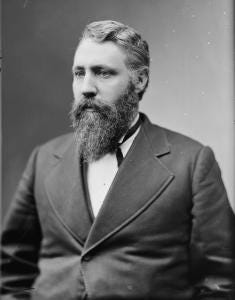

The Republicans were the majority party in the 47th Congress (1881), but 7 candidates sought the GOP speakership nomination in conference. Sixteen nomination ballots (and six hours) were needed before J. Warren Keifer (OH) was chosen.

The Democrats were the majority party in the 52nd Congress (1891), but 6 candidates sought the Democratic speakership nomination. Thirty nomination ballots (over two days) were needed before Charles Crisp (GA) was chosen.

In each case, the majority party came together and elected their nominee (Keifer and Crisp) on the floor — on the FIRST speakership ballot. In 1881, the Republicans faced a real challenge in getting Keifer elected Speaker on the floor, as they commanded only 146 of 293 House seats. Despite real conflicts in the Republican conference, all 146 Republicans — along with three minor party members — voted for Keifer, electing him Speaker. In 1891, the Democrats had a significant majority, so there was the real possibility that the Democratic division in caucus would spill out onto the House floor. But, as we note in our book, “Crisp was elected with the full support of the members who attended the Democratic caucus the previous night” (Jenkins and Stewart 2013, p. 278).

Tracing back to the Civil War/Reconstruction eras, majority parties have settled their fights over the speakership in caucus/conference, presenting a united front when the House organized. The losing majority-party factions — including the leaders of these factions (who sought but failed to get the party’s speakership nomination) would then be compensated with prime committee assignments. Republicans began this tradition when the House reconvened in 1863. Democrats kept with the tradition when they returned to a majority in 1875. This practice evolved into something we call an “organizational cartel,” which was a necessary condition before the majority-party “procedural cartel” (ala Cox and McCubbins 2005) could be developed decades later.

Today, the mechanisms at the heart of the organizational cartel are (arguably) much weaker. And this might be more meaningful for the Republican Party, given the goals of their most extreme members. Stewart and I discussed this in a recent paper update to Fighting for the Speakership. To sum up, there have been changes internal and external to Congress in recent years — leading to the diminishment of committees, the tightening of the procedural cartel, and the weakening of party leaders’ control over members (especially on the Republican side of the aisle) — that were necessary conditions for the organizational cartel to crack. But they were not by themselves sufficient. The narrow Republican majority in the House meant that the small group of GOP dissidents was pivotal — and this was the sufficient condition. Unless (or until) the national electoral environment shifts dramatically, we argue, weaknesses of the organizational and procedural cartels will continue to exist.

Returning to the subject at hand — what do we expect to see tomorrow in the Republican conference? It seems likely that an extended nomination battle will occur. And even if one of the candidates receives majority support in the conference (and thus the Republican nomination for Speaker), it is hard to see how that candidate will reach 217 votes on the House floor. This might suggest some arrangement to allow the “reversionary point” — Speaker Pro Tempore McHenry — to be granted full (or some semblance) of true speakership power until a Speaker can be elected. And given the difficulties there, McHenry could retain his (enhanced) position for some time.