How War Made the State? Latin America’s Piece in the Puzzle

By Luis L. Schenoni

Since Charles Tilly declared that “war made the state,” the formation of modern national states has been viewed through a distinctly European lens. In the face of external threats, European rulers had to build large militaries, taxing and conscripting their populations in a process that demanded robust bureaucracies and a coercive apparatus to repress dissent. Culminating in the total wars of the twentieth century, the succession of European wars brought about some of the most powerful states in history, capable of providing an unprecedented array of public goods and casting a long, Orwellian shadow over society. This “bellicist theory” remains uncontested in Europe and is to some the dominant paradigm in state formation across the social sciences and humanities, yet it continues to face critiques from the Global South concerning its Eurocentric biases. In Latin America, notably, the theory’s validity has been systematically contested.

A Latin American Exception?

Latin America has been showcased as an exception ever since Miguel Centeno, a disciple of Tilly, claimed that while Europe’s state formation was driven by intense and frequent wars, Latin American states faced mild and infrequent conflict, often financed through foreign loans or customs duties rather than extraction from the local population.

A long list of works have since repeated variations of this argument despite a consequential shift in the literature: In the past two decades, scholars of Latin America have come to agree that the factors that made the state in this region were present in the late nineteenth century and not in the twentieth century.

This turn to the nineteenth century is consequential because Latin America was then more violent than Europe in terms of inter-state conflict—it saw almost twice as many wars, lasting twice as long on average, and producing a similar number of deaths despite lower populations and outdated military technology. Conversely, Latin America became the most peaceful region in the world in the twentieth century, with no major war after the Chaco War of 1932-35, potentially explaining the paucity of state formation since then.

Yet, the formulaic repetition of Centeno’s arguments for this completely different historical period raises the question: Why have scholars not given war a chance in the nineteenth century?

Fitting the Latin American Piece of the Puzzle

In my new book Bringing War Back In: Victory, Defeat, and the State in Nineteenth Century Latin America (CUP, 2024), I argue that, while Latin America’s disengagement from the total wars of the twentieth century might account for much of its lag in state capacity today, war in the nineteenth century was frequent and severe enough to explain a quick catch up with Europe—think of countries like Argentina, which had the fifth GDP per capita in the world and world-class literacy rates at the turn of the twentieth century. Moreover, war can explain variation within the region that took place back then and goes a long way to explain the regional hierarchy of state capacity even in our day.

The most recent wave of scholars focusing explicitly on the nineteenth century has overlooked the impact of wars because of two misinterpretations of bellicist theory. First, there are those who understand that wars need to outselect or eliminate weaker states. These scholars correctly conclude that this selection logic does not apply to Latin America (where almost no state died), but they get the theory wrong.

The second mistake is that of scholars who expect mobilization for war to have immediate effects on state capacity, producing a sudden jump to new region-wide levels by virtue of a so-called ratchet effect. Such scholars tend to point out that wars in Latin America produced temporary increases in military size or taxation, but the military was downsized and taxes cut after the conflicts. They also tend to point out that, while certain countries seemed to benefit from war, others were weakened by it. However, by expecting all change to take place during mobilization and across all contenders, these scholars overlook the theory’s implications for post-conflict dynamics.

In Bringing War Back In, I offer a different interpretation. While certain types of state capacity develop during wartime mobilization (coercive and extractive capacity) state building will only accumulate and expand to other dimensions (infrastructural capacity) when wartime policies and political coalitions are legitimized by victory. Defeated states, on the other hand, will experience a similar initial boost in military size and taxation before the war outcome is revealed but will see these policies lose legitimacy after the end of the war and experience a prolonged decline in all types of capacity thereafter. This long-term perspective aligns with the original views of scholars like Otto Hintze and Max Weber, who formulated the theory over a century ago. I call this version of the theory “classical bellicist theory” to underscore this fact.

In sum, classical bellicist theory expects two stages. First, mobilization will influence both contenders, basically triggering the extraction coercion cycle during a preparation for war phase. Second, war outcomes will set winners and losers into divergent state capacity trajectories. By this process, state capacity in the region (which tended to concentrate in colonial centers at the time of independence) would have shifted towards the winners of international wars during that era, and away from the losers.

The Extraction-Coercion Cycle

A key chapter of my book examines whether wartime mobilization initiated the extraction-coercion cycle—the first stage of the model. This analysis involves critically testing several assumptions in the literature: a) that Latin American wars were primarily financed through foreign loans, b) that customs duties served as a significant source of war funding, c) that reliance on external revenue sources allowed rulers to avoid domestic taxation, and d) that by circumventing domestic extraction, rulers were able to prevent internal rebellions and didn’t need to strengthen the state’s coercive capacities.

I test these assumptions by looking at the effect of militarized interstate disputes on outcomes like debt acquisition, tariff levels, and revenue collection. My analysis reveals a different story. If we look at a panel of Latin America from independence until 1913, inter-state conflict either had no effect or led to lower (rather than higher) tariff revenue, tariff levels, and loans. Instead, militarized disputes are associated to currency depreciation, a form of domestic inflationary tax.

Moreover, via the indirect taxation of the local population, interstate militarization had the expected effect of increasing domestic conflict. My analyses reveal that coups and civil wars were twice as likely in the context of international warfare, confirming that the coercive side of the extraction-coercion cycle was also triggered by war.

These findings offer a revised perspective on nineteenth-century Latin America, aligning more closely with the region’s documented history of sovereign debt defaults, exclusion from international financial markets, and naval blockades. Such conditions would have hindered the ability to finance wars through foreign resources and forced leaders to tax and repress locally. These findings turn our previous understanding of war and the state in nineteenth century Latin America upside down and realign it with the work of historians.

War Outcomes and State Building in the Long Term

This documented short-term mobilization, however, provides limited insights into the long-term development of state capacity after these wars. While practices such as seigniorage required states to enforce a unified currency, and suppressing uprisings necessitated policing, these measures may have been temporary responses aimed at addressing the immediate demands of wartime mobilization. The crucial aspect of this puzzle lies in how war affected lasting institutional structures.

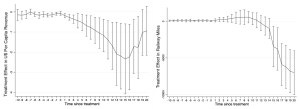

To address this, I investigate how the outcomes of wars influenced state development in their aftermath, with particular attention to the evolution of extractive and infrastructural capacities. In the late nineteenth century, almost all Latin American states engaged in wars, and were divided into groups of winners and losers based on the outcomes of these conflicts. Many of these wars were closely contested, and a Clausewitzian argument can be made that chance played a significant role in determining their results. This framework allows for a difference in differences design that, considering a wide range of potential covariates, I use to estimate how the outcomes of these wars influenced state building. For more details about the models, robustness, etc. see this AJPS piece and appendix.

When I focus on railroad mileage and per capita revenue, my findings suggest that losing a war led to a significant reduction in these indicators of infrastructural and extractive capacity. Pre-treatment coefficients (among other tests) suggest parallel trends, while post-treatment coefficients show effects persist for over twenty years. This demonstrates that the impact of war outcomes on state capacity is not due to the immediate destruction produced by the war and is both long-lasting and incremental, as classical bellicist theorists had suggested (remember the figures above?).

Case Studies

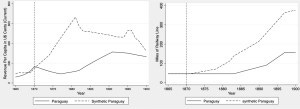

While the book includes cross-national analyses, it also delves into case studies of severe international wars—defined as conflicts with high casualties and substantial military losses. These narratives cover five wars in considerable depth and at least twelve wars in some detail. Furthermore, the case studies span almost all Latin America and offer individual explanations for the trajectories of each country. These case studies are crafted with reliable third-party accounts of what was going on in the wars (usually archival material from the Department of State and Foreign Office) and is helped by statistical analyses of individual cases. For example, using the synthetic control method, the book illustrates how countries would have had looked like in the event of having avoided military defeats.

Overall, the case studies highlight key instances of warfare, such as the Paraguayan War—vividly captured in the artwork of Cándido López (as seen above)—which, alongside the Crimean War, stands as one of the most lethal inter-state conflicts of the period spanning 1815 to 1914. These confrontations compete for the grim distinction of being the deadliest in the world during this era.

Setting the Record Straight

Bringing War Back In demonstrates that, when interpreted correctly, bellicist theory provides valuable insights into state formation processes in both Europe and Latin America, and that the Latin American mirror can help underscore elements of the theory that are lost when we look solely to Europe.

Centeno was right that the lack of total wars in the twentieth century left Latin America behind in the race for state capacity, but the impact of nineteenth century wars should be deemed undeniable after this book. Future work could explore to what extent the current ranking of state capacity in the region can be traced back to those dynamics, as well as the many subnational implications of the argument.

Finally, this study of Latin America offers an optimal context for refining bellicist theory, which has previously been obscured by the process of state elimination in most other regions. In Europe, the disappearance of many states complicates the assessment of the long-term effects of war outcomes on state building and thus this element of the theory features less prominently. By contrast, Latin America provides clarity on this aspect of the theory, highlighting this overlooked dimension, and opening a new avenue of research about the effects of war outcomes.