How the World Became Rich (Part I)

The world is rich. Yes, it is certainly true that not everyone is rich by either historical or contemporary standards. But the world is richer than it has ever been. A smaller fraction of the world’s population is in dire poverty than ever before. And there is reason to believe that much of the worst poverty in the world will be eradicated over the next century.

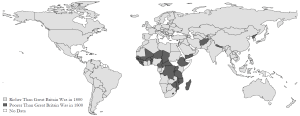

Don’t believe me? Check out these two maps. The first shows countries that are currently richer (in terms of real per capita GDP) than the US was in 1900. The second shows the same comparison for Britain in 1800. At the national level, that is most of the world! And here is the thing: the US was the world’s richest country in 1900 and Britain was the world’s wealthiest country in 1800. While there is still a long way to go, the fact that most countries are wealthier than the world’s wealthiest country was just a century or two ago is a remarkable achievement.

Five Sets of Theories for how the World became Rich

How did this come to be? How did the world become rich? These are the questions I try to answer in my forthcoming book with Mark Koyama, How the World Became Rich: The Historical Origins of Economic Growth (available for pre-order!; the two figures above are the first two figures in the book). These are not easy questions to answer, and they have occupied the minds of many a brilliant scholar for well over a century. Where can we even begin?

The first half of our book attempts to classify five major strands of theories of the historical roots of modern economic growth. I will not go too deeply into any of these here—I plan to do that in much greater detail in future Broadstreet posts. We view the five dominant explanations as falling into the following categories:

Geography: theories based on geography, such as the one famously put forth by Jared Diamond in Guns, Germs, and Steel, link some aspect of a nation’s geography to its long run development. This includes access to seas or oceans, access to certain natural resources, the disease environment, the alignment of the continents, access to domesticable plants and animals, ruggedness, climate, and weather variability. What do certain advantages mean? How can impediments be overcome? (not to be self-promoting, but buy the book to find out! Or, just wait until my next Broadstreet post…)

Institutions: ever since Douglass North attempted to resituate the study of economic growth around institutions, they have received significant attention in the economic history literature. Various theories focus on legal institutions (and the origins of those institutions), political institutions (especially those that constrain executive power and/or are broadly inclusive), and economic institutions (e.g., merchant guilds, banks). These institutions have implications for the protection of property rights, economic freedom, political voice, state finance, conflict, and much more. Unlike geography, institutions are human-made and may change over time. But what does this imply for long-run economic growth?

Culture: a large literature has recently emerged connecting various cultural attributes to long-run economic growth (I covered some of this literature in my first post on Broadstreet!). By “culture,” we mean it the way cultural anthropologists like Joseph Henrich mean it: it is a set of learned rules of behavior that can be transmitted across generations. Various cultural attributes have economic implications, including what type of work gives one status, racial norms, ethnic norms, gender norms, the importance placed on education, religious values (as I have laid out here, here, and here), trust of outsiders, family structures, and incest taboos. One reason why culture can have such an impact on long-run economic development is that it persists. If there is one thing this literature has shown, it is that once cultural norms arise (for whatever reason), they are hard to shake. But just how does this translate into different growth trajectories for different societies?

Demography: theories based on demography date to Thomas Malthus, who famously argued that any temporary advancement in human welfare would eventually be eaten away by population growth. Although not an unreasonable proposition at the time Malthus lived, this theory does not explain how the world became rich; it has done so in the face of rapid population growth. What, then, do demographic theories offer? For one, they provide some insight into how large demographic shocks like the Black Death affect economic outcomes. They also shed light on when women enter the work force, how many children they have, and why this differs across societies. The Demographic Transition—that move to have a lower “quantity” but higher “quality” children (i.e., higher educated)—was responsible, at least in part, for maintaining high incomes. But was it enough to explain how the world became rich?

Colonization: was it just a matter of exploitation by European colonial enterprises? The colonial past is dark indeed—the slave trade, mass killing of native populations, and resource exploitation are just a few of the colonial legacies. It is undeniable that colonization played a large role in exacerbating divergence between the colonizers and the colonized. But can such theories explain the divergence in the first place? Can they explain the onset of industrialization? What were the various effects of colonial rule on those in the colonies? What role did this play in the world becoming rich (or, in some places, remaining poor).

Which Theories Best Explain the Emergence of the Modern Economy?

In the second half of the book, we bring the theories together to try to better understand which best explain the timing and location of the onset of modern economic growth. Any satisfactory answer has to explain, to some extent, why northwestern Europe became rich first.

Future posts will delve in much greater detail into the specifics, but the TL;DR version is that to understand why the world became rich, it is not enough to focus solely on any of the five sets of theories noted above. What is key is how these theories interact with each other. Certain institutional changes were key in Britain and the Dutch Republic, but they can only be understood in a certain cultural context. The same can be said for non-European countries that eventually caught up, such as Japan (beginning in the late 19th century), the East Asian Tigers, or contemporary China.

Similarly, geography can often have an important role on a society’s long-run economic trajectory because of the way it shapes political and economic institutions. The connections between a society’s colonial past and modern outcomes is likewise moderated via culture, institutions, and demography.

The second half of the book thus tells the story of how the world became rich as the result of numerous factors which interacted with each other. History is messy. It is rarely monocausal, especially when such a long time span is considered. But this does not mean it is unexplainable. We hope that this book will help better our understanding of how various societal features interact with each other, and why what works in some places does not work in others.