Folklore comprises the unrecorded traditions of a people — the collection of traditional customs and stories passed through the generations by word of mouth. For anthropologists, “the relation between myth and ritual has been frequently discussed, to say nothing about the relations of myth to the prevailing world view and to religion” (Hallowell 1947). Folklore is generally considered to reinforce a system of beliefs about relationships between the universe, man and society.

Yet, little systematic research explores the relation between folklore and culture (Bascom 1953). While traditional folklore has often been carefully transcribed, Hallowell observes that it “is an open secret that, once recorded, very little subsequent use may be made of such material”; in other words, there is “a failure to exploit fully the potentialities of such data”.

A Systematic Outlook Over Folklore

When I visited Brown in 2017, both Stelios and I were interested in the role of traditional narratives (fairy tales, proverbs etc.) in transmitting cultural values. After some exploratory research, we noticed the huge potential of a folklore catalogue compiled by Yuri Berezkin. This resource led us down the path toward writing a paper about folklore and culture.

In recent years, economists have been fascinated by how attitudes and beliefs shape economic outcomes, however one challenge is that little is known about attitudes and beliefs in societies that are made distant by either time or location. Berezkin’s Folklore and Mythology Catalogue presents a unique opportunity to investigate these dimensions.

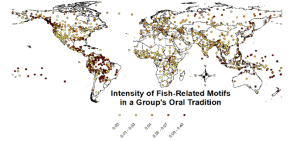

The Catalogue covers 958 societies and 2,564 motifs (Figure 1). That is to say, 958 oral traditions share 2,564 motifs; each oral tradition is made up of a varying number of motifs drawn from these 2,564 motifs. A motif describes an image or an episode in the group’s oral tradition. The most widespread motif, k27n, “Father or other kinsmen of hero’s wife or bride try to kill or test him and/or suggest to him difficult tasks”, is found in a total of 355 oral traditions.

Rooted in anthropological field research, the Catalogue has a superior coverage for Asia, Africa & Americas, which sets it apart from the more traditional index used by folklorists, the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index. The ATU has a regional focus on Europe and was produced in a different intellectual tradition (rooted in literary methods).

Beginning with this Catalogue, we produced a dataset of historical traits for these 958 societies based on the content of their folklore. Our paper is the first to decode and analyze folklore on a systematic basis, and examine its relationship to modes of production, polity, trade, gods, as well as modern-day attitudes, beliefs and development outcomes.

Methodology

The basic unit of the Catalogue is a motif, or story elements, whereas the basic unit of a dataset we intend to build is a particular trait of a society. As no one had attempted to use the Catalogue for our intended purpose, it was not obvious ex ante how we would go from a motif to a societal trait.

The basic idea we follow is that how a motif speaks to a particular trait—whether positively or negatively—and its presence or absence in a group’s oral tradition together explain how inclined a certain oral tradition is towards a particular trait.

The first step is to “read” a motif. This step can be done either through text analysis or by human beings, depending on what type of information we needed to extract.

Human subjects play a vital role in digesting motifs in a holistic fashion. Their participation is essential to assess the relevance of a motif for high-level, abstract concepts, such as trust, risk-taking and perception of women.

In text analysis, we invoke knowledge graphs (ConceptNet). For each seed word we enter, ConceptNet spits out the most relevant # words, forming a cluster of words related to each other. This approach gives us some assurance that we are accounting for different words being used in describing the same underlying concept.

For example, “head of the state” could be a king, an emperor, or a sultan, depending on the context. All three words are related to each other in ConceptNet and are functionally the same in our analysis. In our search for king-related motifs, motifs with any of the three words are treated as having relevant information for “head of the state”.

The process of mapping motifs into specific traits can be incredibly noisy. On the plus side, most oral traditions have more than just a few motifs, so we almost never have to rely on just a few motifs to decide what a society is like. This approach will produce correct values for each specific trait at a group/country level, if we get the meaning of motifs right on the average. Figure 2 is a map for fishing-related motifs. Most costal areas appear to have a higher share of fishing-related motifs.

In subsequent analyses, LASSO is employed to automatically select clusters of words that are most predictive of a specific trait. In one example, LASSO selects “competition” and “competitive” as predictors of attitudes towards risk-taking. These are typically motifs describing heroes going into contests or expeditions. Building on this insight, we take these motifs to Amazon Mechanical Turk, and have them further classified into heroes succeeding in contests versus heroes ending in tragedy. As expected, societies with successful hero stories seem to have a more favorable view towards risk taking.

Among folklorists, Tim Tangherlini is on the frontier of studying folklore using computational methods, a pioneer of computational folkloristics. We have a different focus in our study: We ignore the internal structure of motifs and focus instead on whether it provides information relevant for traits to be examined.

How are women portrayed in folktales?

The perception of women is one of the cultural norms we examine in the paper. Both men and women are frequent characters in virtually every society’s oral tradition. One advantage of studying a universally present plot is lowered exposure to sampling bias. For that matter, cross-cultural variation in attitudes towards women can be readily explored using the Catalogue.

In social psychology, gender stereotypes are labeled as communion and agency (Bakan 1966). Communion concerns the well-being of others, such as being affectionate and emotional, and is more associated with females; agency concerns one’s own mastery, such as being ambitious and courageous, and is commonly associated with males.

In the Catalogue, the most common representation of male characters is being violent, dominant, and arrogant – 33% of all 801 motifs with male character(s). Meanwhile, only 14% of the 748 motifs about women depict a violent, dominant and arrogant female. In contrast, about 30% of these 748 motifs depict women as submissive and dependent.

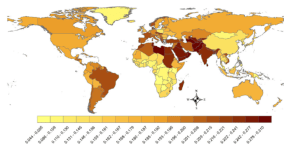

Combining text analysis and human-based methods, we construct a “male bias” variable to measure the gap in the way men and women are portrayed in folklore. On average, males are portrayed as more dominant, less submissive, more intelligent, more physically active, and less likely to engage in domestic affairs. But there’s a tremendous amount of variation in male bias around the globe (Figure 3). The gap is smallest in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia.

Are these stories a mere reflection of archaic customs no longer in actual practice? This is the view often held by anthropologists and folklorists of the Cultural Evolutionary School, who view folklore as “survivals” from earlier stages of civilization. Our empirical examination, however, suggests a tight link between historical and modern attitudes and beliefs.

… the narratives they choose to transmit from generation to generation and to listen to again can hardly be considered unimportant in a fully rounded study of their culture. When, in addition, we discover that all their narratives, or certain classes of them, may be viewed as true stories, their significance for actual behavior becomes apparent. For people act the basis of what they believe to be true, not on what they think is mere fiction (Hallowell 1947).

Figure 4 shows male bias in oral traditions is negatively associated with female labor force participation in 2019, suggesting that women are less likely to participate in the labor force if they are in a country with a strong male bias in its oral tradition.

This result can be reproduced using a sample of second-generation immigrants in Europe: women are more likely to be housewives if their parents are from a country with a strong male bias in its oral tradition. Using the same sample, male bias in oral traditions is found to predict contemporary attitudes and beliefs such as “Men should have more right to a job than women, when jobs are scarce” and “Women should be prepared to cut down on paid work for the sake of family”.

It is also possible to verify this relationship at an ethnic group level: male bias is stronger in groups in which men contributed more than women in agriculture historically and in which the plow is indigenous to society.

Our approach does not maximize the potential of each individual story. Indeed, compared to humanities scholars, we do not have the advantage of performing a literary analysis of folktales; or to anthropologists, who are trained to record not just stories, but emotions of the performer and reactions of the audience, providing the full social context of the stories.

From a methodological point of view, our approach makes the necessary assumption that across societies, there is a shared element in the same motif. In doing so, we give up on many sources of variation such as differences in local contexts. In this sense, the variation we do find is likely an underestimate of the true variation in oral traditions across societies.

As the bulk of the stories under study have been collected in the 19th century or early 20th century — a time when colonialist and racist views prevailed — a natural concern is to what extent the worldview of the collectors was shaped by the era and by their own background. Their perspective could have impacted the type of stories being collected for a given society and the way they were recorded. In this regard, our hope is to eventually build a database on collector identity which can help us understand the systematic influences of collectors on our knowledge of a given society’s oral tradition.

Future work

Seen by some as irrational, outdated, marginal and irrelevant, here folklore is instead shown to a powerful predictor of cultural values, suggesting that there is a historical component to modern cultural values that persists in folklore.

There are a number of directions in which this project can be taken. As part of culture, folklore can be used to test different theories of culture, such as cultural diffusion and cultural integration. The study of folklore complements research in a number of areas: its close connections to peasant life makes it a useful resource for studying histories of peasants; folklore is the repository of pre-Christian beliefs in Europe and an active component of indigenous religions; and folklore has a vital role in personality formation as studied in child development.

While we focus specifically on folktales in this paper, folklore also takes the form of folk songs, folk dances & ancient poems, which can be studied independently.A deeper exploration of these repositories of traditional beliefs can add to our understanding of the historical component of cultural values and how history influences the modern world through culture.