Ethnic diversity as an outcome: the coevolution of state capacity and racial demography in Brazil

Ethnic diversity as an outcome: the coevolution of state capacity and racial demography in Brazil

What are the effects of ethnic and racial diversity on local communities? With the rise of racial justice and immigration debates in the US and other countries, many politicians and policymakers feel compelled to take a strong and principled stance against or in favor of increasing diversity. A common argument is that diversity can undermine public goods provision and other important outcomes due to the greater potential for intergroup antagonism and communication problems, or simply due to group differences in policy preferences. Many academic studies do find empirical support for this hypothesis by comparing diverse and homogeneous communities. Diversity has been found to be correlated with poor governance and distribution of public goods, low generalized trust, reduced social capital and lower economic development.

These findings, however, have recently been challenged. For instance, some scholars have demonstrated that the observed negative effects of diversity can often be the result of a statistical artifact. At the same time, other work has noted that the observed relationship between demographic diversity and public outcomes may be endogenous (i.e., suffer from reverse causality or be caused by other factors). Indeed, what do we know about why some communities are more diverse than others in the first place?

As we show in our new research using data from Brazil, both contemporary ethnic demography and public outcomes can be influenced by the historical distribution of state presence across space. We show that more remote Brazilian municipalities with lower levels of state capacity in the past were more frequently selected by escaped slaves to serve as permanent settlements. Consequently, such municipalities have worse public services and larger shares of Afro-descendants today. These results suggest the failure to consider the trajectory of state development and the different migration incentives of ethnically diverse populations can undermine the validity of previous findings regarding the costs and benefits of any particular demographic composition.

Ethnic diversity as an outcome of state capacity

Although scholars have long acknowledged the endogenous relationship between ethnic demography and public outcomes, few studies have taken into account the historical processes that can influence the distribution of ethnic groups across space, and even fewer have been able to identify plausibly exogenous sources of variation in ethnic demography (for one excellent example, see this article by Volha Charnysh).

Because groups are rarely randomly assigned to different territories, it is difficult to uncover causal relationships between demography and collective outcomes using observational data. Even more challenging, however, is the task of identifying the causes of change in demographic diversity across space and time.

Among the various factors that may simultaneously influence subnational demographic structures and public outcomes, our research focuses on variation in local state capacity, or the reach of the state and its ability to govern across different areas of its territory.[i] From the use of explicit “demographic engineering” measures to the adoption of more benign and (ostensibly) colorblind policies such as land use regulation, states may intensify ethnic segregation and exacerbate pre-existing spatial inequalities. Whether deliberate or unintended, it is easy to see how far-reaching the consequences of state policies can be when we consider that even small compositional differences across groups (for example, in their average income) can lead to heterogeneous responses in terms of birth, death, intermarriage, and migration rates.

We argue that the willingness and ability of different ethnic groups to settle in better-serviced areas within a given territory can be constrained by their socioeconomic status and by their historical relationship to governmental power. Although these constraints might be temporary, their effects can unfold over time in a cumulative manner. Therefore, statistically accounting for the contemporary compositional characteristics of communities or other relevant proximate factors, such as average levels of social spending, might not be enough to address endogeneity issues.

As these observations suggest, looking at demography as an outcome rather than a fixed attribute may help us better understand the nature of the link between diversity and the provision of collective goods.

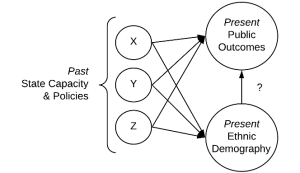

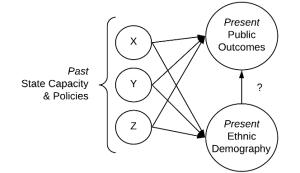

X, Y, and Z represent common antecedent factors influencing both present public outcomes and ethnic demography

The case of pre-Abolition Brazil and the race-based selection into low state capacity areas

To investigate the emergence of more versus less homogenous communities, we focus on the case of Brazil. Racial cleavages in the country have often been described as “fluid,” and the lack of race-based legislation following the abolition of slavery was historically used to propagate the myth of Brazil as a racial democracy. In this sense, Brazil constitutes a puzzling case. The porousness of racial boundaries and the nominal equality of rights across groups since the 1891 constitution should have contributed to the progressive attenuation of racial disparities in the country. Nonetheless, racial identities remained tied to divergent opportunities, access to resources, and experiences of the state.

Brazil was the largest receiver of enslaved migrants during the Atlantic slave trade era and the last country in the West to abolish slavery in 1888.[ii] Between the 16th and 19th century, 4.8 million Africans were forcibly displaced to the country. However, as scholars have increasingly emphasized, enslaved populations were not just passive recipients of exploitation during this period. Rather, they actively resisted domination by Portuguese colonial authorities and, later, by the Brazilian state and slave owners (see also Edgar Franco-Vivanco’s recent post on the agency of native populations in Mexico during colonialism). One of the basic forms of resistance was the formation of independent, self-sustaining communities of fugitive slaves in the hinterlands. These settlements, called quilombos or mocambos, were numerous, long-lasting, and widespread across the territory[iii] – something that likely relates to the openness of the Brazilian frontier.

We focus on the location of quilombos to explore one of the channels through which the historical presence of the state may have influenced the geographic distribution of racial groups across the country. Reflecting the fact that fugitive slaves had strong incentives to avoid areas of high state capacity, homogeneous communities of Afro-descendants were more likely to form in remote, inaccessible areas where state institutions were virtually absent.[iv]

Since Brazil’s independence, the primary responsibility for investments in social overhead capital and public services has been in the hands of municipal governments. The fact that localities had to finance public goods with their own resources, in turn, meant that without a robust apparatus capable of generating revenue effectively, they could not fulfill their mandated responsibilities.

Findings

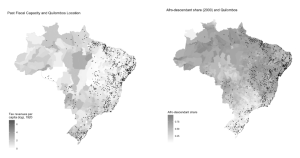

Our findings show that localities that had lower state capacity more than a century ago have worse public goods provision andlarger shares of Afro-descendants today. This relationship persists even after we account for range of geographic and other confounding factors. We then show that part of the association between public goods provision and Afro-descendant shares we observe today can be traced to the strategic selection of quilombo communities into hard-to-reach areas where state capacity was minimal and took longer to develop over time (see Figure below).

Past State Capacity, the Location of Quilombos, and Racial Demography

We then examine whether the logic of race-based geographic exclusion applies beyond quilombo territories and provide suggestive evidence for three additional mechanisms explaining why local state capacity may have continued to play a central role in the spatial distribution of ethnic groups in the decades after emancipation. The first mechanism emphasizes the role of labor market discrimination and immigrant competition. Following Abolition, political and economic leaders attempted to carry out a policy of “whitening” and European immigration constituted an important pillar of this strategy. Because foreign workers generally enjoyed preference in hiring, their presence in large numbers may have displaced and marginalized Afro-Brazilian workers, forcing them to retreat to more depressed areas in the country.

The second mechanism emphasizes the use of state’s repressive apparatus. In areas where immigration did not provide an expanded pool of workers, other forms of planter-state cooperation emerged to resolve the problem of labor recruitment and social control. One of the central aspects of this partnership consisted in planters’ increased reliance on state enforcement mechanisms as a means of generating cheap labor and controlling the newly emancipated Black population. The ability of the state to arrest, impose sanctions, and enforce vagrancy statutes may thus have discouraged the settlement of Black and mixed-race individuals in certain areas.

The third mechanism emphasizes uneven access to land. At least two reasons made access to land in high state capacity areas more difficult: first, the closeness to valuable state infrastructure (i.e., roads, bridges, etc.) made land more expensive; second, the chances that small farmers would eventually be evicted or displaced at the hands of fazendeiros or other speculative interests was greater. As a result, many Afro-descendants may have sought out peripheral regions to gain access to land.

In short, although the initial association between local capacity and the share of Afro-descendants could have faded over time as the state extended its reach, it did not. These mechanisms illustrate some of the reasons behind the persistence of this association, but the list is far from exhaustive. If, in addition to these channels, bureaucrats found it harder to penetrate and collect accurate information from communities with higher shares of Afro-descendants, identity itself may have played a meaningful role in the differential evolution of bureaucratic institutions across space, as discussed by Pavithra Suryanarayan in a recent post.

What does this mean for how we understand the role of diversity elsewhere?

Although we cannot claim the mechanisms we describe here are widespread, we believe that the idea of differential group-based incentives to select away from the grip of the state is generalizable. The literature suggests that these dynamics of freedmen seeking out more remote areas are not confined to the case of Brazil. In Jamaica, for example, the post-emancipation peasantry migrated to peripheral areas and bought small properties where they relied on subsistence agriculture and the sale of surplus production in nearby markets. While Afro-Jamaican peasants initially established their settlements near large estates, over time “the search for available land took settlers further and further into the interior of parishes.” In the case of Cuba, the eastern side of the island has attracted most Black migrants after full emancipation. The east offered greater access to land in part due to its mountainous interior, which was not conducive to large-scale sugar production, leaving room for the development of a nonplantation sector.

Although our research focuses on the association between state capacity and public goods provision, our argument is likely applicable to other collective outcomes. For instance, another issue that has attracted considerable attention concerns the detrimental effects of ethnic diversity on social capital and trust. But recent evidence has also shown that prior investments in state capacity can promote persistently higher levels of social capital. Therefore, to the extent that ethnic diversity is itself influenced by state capacity, as discussed here, its previously uncovered effects on social capital may be spurious.

Previous research has associated ethnic homogeneity with a host of positive outcomes, arguing that it facilitates collective action, the aggregation of preferences, and norm enforcement. Without questioning the validity of these mechanisms, our results indicate that the ability of different groups to gain access to the potential benefits of coethnicity may be strongly conditioned by these groups’ historical relations to state power. They suggest that the failure to account for past levels of state capacity and other relevant, context-specific, historical factors may call into question previous observational findings regarding the social costs and benefits of any particular (diverse or homogeneous) ethnoracial demographic composition.

[i] Following other scholars, we conceive of state capacity as consisting of three main dimensions: administrative, coercive, and extractive. We operationalize it using a taxation measure, but we present additional analyses using alternative measures such as the size of the bureaucracy and size of the coercive apparatus.

[ii] To understand more about the differences in the willingness of elites to support abolition, we recommend reading the illuminating Broadstreet post by François Seyler and Arthur Silve.

[iii] Google Earth website created by ARQMO, Associação das Comunidades Remanescentes de Quilombos do Município de Oriximiná.

[iv] Not all communities were formed by runaway slaves or were established in isolated areas, not all of them have survived to this day, and only a fraction of those that did have been officially recognized as quilombola descendants. Therefore, the distribution of quilombos we observe today presents at best an incomplete picture of the prevalence of these communities across the territory. This speaks to the challenges of archival silences, highlighted by Emily Sellars in an earlier post, and the need to triangulate between several imperfect solutions to deal with data limitations.