Discover more from Broadstreet

Ethics and Archival Research on Violence

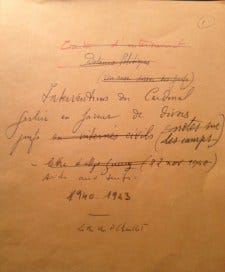

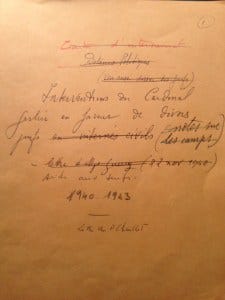

(Contrasting letters written by Hilda Dajč describing her different feelings about violence in the Semlin Nazi Death Camp, (Left) December 1941 and (Right) Spring 1942).

By Aliza Luft and Jelena Subotić

Historical data is increasingly mined for social scientific research on violence, yet its ethical challenges are rarely discussed. Instead, archives are seen as neutral sites and sources to be probed, or complex sites and sources to be resolved through triangulation (or propulsion). In this blogpost, we argue with examples from ours and other research that ethical issues undergird methodological issues in archival research on violence, shaping outcomes in turn. We identify three ethical minefields—politics, interpretation, and harms and benefits—and suggest ways forward.

Politics

Archives are not neutral. Rather, the political-historical context in which documents have been gathered and placed in archives shapes how they have been categorized, classified, and made available, guiding their use. This is especially the case for scholars who work with conflict archives, as archival integrity principles are complicated when documents become privy to battles over how to “repair a broken world.” Such battles can be fought during a conflict or its aftermath, and among different populations invested in possession.

Consider the US Invasion of Iraq: in 2003, American Armed Forces confiscated Ba’athist Party Archives, which they claimed were necessary for counterintelligence. However, Iraqis and Middle East scholars decried these actions as cultural theft in violation of the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict. They have since called for their return. While this battle continues, the documents remain in Hoover Archives at Stanford, and they have been mined by social scientists to craft path-breaking, valuable research.

Yet the politics surrounding these documents reveal they cannot provide an unfiltered lens into the past. These documents were confiscated during wartime by an invading country that has selected which collections to release for research, how to catalog and organize them, and which to keep hidden. Hence, the ethical problems of crafting research on Ba’athist Iraq using these archives invariably affects the empirical process. The politics undergirding the archives’ provenance and placement bear on Hoover’s entire Iraqi Collection.

It is not, however, only warring states that conflict over where documents belong. During and after genocide, victimized populations can also clash over the placement and purpose of documents. In the wake of the Holocaust, for example, surviving Jews in France felt as if their documents would best be used to obtain restitution and reintegrate Jews as citizens. Meanwhile, refugees and immigrants to the US felt as if the Jewish future was in New York, and so Jews’ past documents belonged there. In contrast, in Palestine, Jews believed archives should serve as the foundation for the construction of a new national community in what would eventually become Israel. Debates over possession became debates over Jewish identity, resulting in a dispersion of documents and the creation of three “conflicting archives” that sought to impart different narratives.

But the politics shaping archives are not limited to archives’ construction. They also influence material production. Continuing with the previous example, in 1943 Grenoble, several Jews formed an organization to compile statistical information on Jews’ dispossession to secure post-war restitution. They did not know Nazis would soon invade Grenoble and murder them. Meanwhile, in the Warsaw Ghetto, Jews organized to form an archive to leave a legacy of Jewish life and culture—music, poetry, newspapers, photographs, art, and more—anticipating they would be killed. Though part of the same genocide, different circumstances shaped why and how documents were constructed, collected, and preserved in each case. Without this information, however, a scholar may think the data they are gathering is representative of general experiences, not experiences shaped by sociopolitical contexts specific to the documents’ “producers.”

The researcher’s role, then, is to first examine the historical context in which documents were created and archives constructed. Archival materials must be embedded within their proper political and social dynamics and include explicit discussion of what might have influenced their production. They must also evaluate what shaped documents’ placement in different archives and their categorization and classification by archivists. During and after violence, select documents are preserved and others hidden or destroyed to suit present politics, others remain unclassified for the same reason, and others may have simply not been catalogued because they do not fit institutional priorities.

Interpretation

A related challenge concerning the ethical use of archives involves evaluating source veracity. This interpretive work is especially important in the context of archival research as it is easy to assume that personal documents, such as letters or diaries, are “truthful”—that is, in conformity with reality as it occurred. Yet personal materials also involve interpretation. People are complex; their narratives about themselves and others are also complex, not directly representative of events, and may change over time. Moreover, sometimes people have reasons to lie or not be fully truthful when writing letters and diaries, particularly about war and violence. Scholars must be attentive to this when working with personal materials.

In situations like these, researchers can compare diaries or correspondence from one person over time, letters from one person to different people about the same event, diaries versus letters, or diaries and letters compared with post-war testimonies and interviews where possible. Such strategies allow scholars to discern how and why people’s narratives about violence change. But to do so, scholars must first be cognizant that no single document can tell the full story of an individual’s experience with violence.

Simultaneously, cognizance is insufficient: scholars must also explain and justify why they selected one document that provides one interpretation of a violent event versus another when writing results. Often in research on violence, scholars extract documents to provide a snapshot that fits an agenda of exposing horror. But snapshots are only part of persons’ experience, and for many victims (and survivors), having only the most awful part of one’s past published in academic work can be exploitative. Thus, researchers are responsible for interpreting evidence not simply in light of arguments they wish to make, but also in consideration of those whose stories they mine to make those same arguments.

Relatedly, scholars must also be explicit concerning archival silences. Power dynamics affect not only how people experience the world but also whose experiences are recorded and stored. For example, though the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database contains quantitative records of this cruel past, we know nothing about who these people were nor their experiences from their perspectives. All we have are logbooks recorded by European officers who perceived enslaved Africans as commodities. These are far from “photographic portrait[s] of reality“—they are biased records crafted by violent actors who described two men jumping off a ship to their deaths in the same cadence as reporting on the weather. A scholar may analyze all available logbooks concerning the violent voyage from West Africa to North America, but without interpretation or “critical fabulation,” it is impossible to tell what this journey was like for its millions of victims.

Consequently, triangulation to deal with missing data is not enough. Though triangulation may combine disparate pieces of the past to create as comprehensive an analysis as possible, it does not resolve the ethical dilemmas of purporting to explain the violent past while crucial perspectives are missing. Robert Braun’s (2019) excellent study of religious minority rescue during the Holocaust in the Netherlands is a case in point: Braun draws on a wealth of archival sources to argue that religious minorities were better able to overcome the collective clandestine action dilemma that rescuing Jews required, and his statistical matching of Jews arrested by Nazis with Jewish war victims and survivors is an impressive methodological feat. Yet we cannot tell from his study if or how Jews played a role in their own rescue, because their voices are missing from the analysis.

Hence, even prior to attempting to “solve” the problem of missing voices, we suggest researchers begin from an ethical standpoint of being explicit in their work about which sources and perspectives are absent and why. What evidence could be available, but is not? Why is it not? How would its presence complicate the story we tell? How does its absence inform the evidence that does exist, which we use to develop our analyses and results? In evaluating the veracity of sources, scholars should also interpret, interrogate, and account for archival silences, and foreground the fact that archives are sites that privilege some voices over others. This is a form of counterfactual analysis that is often missing in historical social science.

Harms & Benefits

Consideration of harms and benefits is typically limited to living people, but attention to archival ethics reveals how many of those whose documents we examine did not anticipate their materials would be available for research nor publicly published. The evaluation of harms and benefits in archival research should therefore address challenges involved in discovering and publishing unflattering documents, including intimate writings and testimonies. Sometimes, sharing this material can cause reputational damage to authors, even after they have died. Hence, scholars should think through the balance of harms and benefits not only in terms of current harms to those implicated in archives, but also possible future harms, such as when a political context changes and uncovered information becomes more dangerous or damaging to subjects in a new environment.

To be sure, one solution is to call for IRB standards of anonymity for private individuals’ data. Yet when it comes to the study of violence, this introduces other complexities. Rachel Einwohner describes the ethical dilemmas involved in working with Holocaust survivor testimonies and erasing names in the write-up phase of research when the purpose of these testimonies is to bear witness. She also describes how assigning numbers to survivors’ testimonies for coding “[has] eerie similarities” to the Nazis’ dehumanizing tactics of tattooing Jews with serial numbers at Auschwitz. IRB guidelines for archives do not currently require anonymization but given that some documents are created specifically because creators want to share stories, it is not clear this is the solution. That we lack a solution to this dilemma, however, does not mean scholars should uncritically use private individuals’ materials. Rather, scholars ought to weigh costs and benefits, including potential future costs, of sharing individuals’ private documents, and explain when and why they make the choices to anonymize a document or not.

Finally, scholars can try and consult with family about the implications of disclosing unflattering materials and ask whether individuals would have felt comfortable with having their materials published. This, however, may bring about a new set of challenges. Family may not want to be associated with the ideas and actions of relatives, or they may be incentivized to obfuscate their documents. They may also, quite simply, not know about this aspect of their relative’s past and so contacting them to discuss it could cause harm to families or descendants of participants in violence or their victims. Our experiences conducting historical research on violence suggest we need to reconceptualize notions of harm and benefit in historical social science, as current ethical guidelines are written with live human subjects in mind. We do not know how to judge the benefit of research to people who have died, especially those who led private lives and did not anticipate becoming a focus of scholarship years later, but we can conceive of groups that can be harmed or owed benefits by such work, suggesting that the issue merits further discussion.

Conclusion

The implications of this post reveal how archival research is never neutral but rather laden with ethical complexities that shape our research. This includes the politics of the past, which shaped how documents were constructed, gathered, stored, and shared; the politics of the present, which shapes how documents are interpreted; and the politics of the future, which shapes how documents might be used or misused for different purposes, causing harm or benefit to various populations. Ethical care should be more central to historical social science than it currently is, and at all stages of a project, researchers should be prepared to make and defend their choices.

Subscribe to Broadstreet

Broadstreet is an interdisciplinary blog dedicated to the study of historical political economy (HPE).