Congress and the Political Economy of Daylight Saving Time (UPDATE)

This weekend, Daylight Saving Time (DST) – which has been a part of everyday life in the United States (and around the world) since the late-1960s – ends.[1] The goal of DST is to preserve as much daylight as possible during the typical waking hours in the summer months. Clocks are shifted ahead an hour, so that an hour of daylight very early in the morning (when most people are still asleep) is shifted to the evening (when people are done working and home with their families or enjoying leisure activities). DST was thus once known as “Summer Time,” and the routine of adjusting clocks follows the pattern of “Spring ahead, Fall back”—that is, clocks are shifted ahead an hour at some point in the Spring and back an hour at some point in the Fall. Since 2007, the start and end dates of DST are the second Sunday in April and the first Sunday in November.

Yet, DST remains controversial. Farmers have generally opposed DST, as losing an hour of daylight in the morning disproportionately affects their “early rise” agricultural work pattern. Parents with young children often raise safety concerns regarding DST, as their children leave for school in the “artificially dark” early morning, which could yield increased accidents and injury on dark roadways. Merchants have generally favored DST, believing that an extra hour of daylight in the evening leads to more commercial activity. And a range of supporters have argued that DST lowers energy consumption – as people are awake and active an extra hour during daylight rather than in darkness – which reduces lighting and heating usage. These interest disputes (and other events) have led Congress to tinker with DST provisions since the early-1970s. Such tinkering has involved shortening or lengthening the time parameters of Summer Time – and, once, even making DST a year-round endeavor.

DST has generated a fair amount of academic research. Economists have taken the lead, studying the effects of DST on energy usage, safety, criminal activity, and stock market performance. Political scientists, however, have virtually ignored DST. In a recent paper, Thomas Gray and I fill this gap by examining the determinants of voting in the U.S. Congress on all substantive measures dealing with DST across American history. Our analysis covers more than 20 legislative measures spanning much of the 20th century, from the initial adoption of DST during World War I (and its subsequent repeal over President Woodrow Wilson’s veto a year later), through the first permanent DST law in 1966, up to the most recent revision attempts and extensions. We examine how member ideology, partisanship, geographic location, and constituency interests affect congressional vote choice. Our results allow us to better understand the political economy of DST and uncover the significant factors that have determined legislative outcomes.

Before discussing our research findings, however, I first provide a short history of DST legislation.[2]

A Short History of DST Legislation in the U.S. Congress

While historians often identify Benjamin Franklin as the first public proponent of daylight saving – via his essay “An Economical Project” – the first modern advocate was British builder William Willett. In 1907, he self-published a pamphlet, “The Waste of Daylight,” that called for time to be advanced in 20-minute increments in April and then reversed in a similar fashion in September. Willet, like many others later, believed this April-September shift would save energy by reducing lighting costs. Unfortunately, Willett died of influenza in 1915, before he was able to persuade British politicians to adopt his system. Shortly after his death, however, his idea gained momentum. As Europe found itself embroiled in World War I, coal – which was burned to produce electricity – grew short. European leaders quickly saw DST as a way to save energy and gain an advantage on their enemies. In April 1916, Germany became the first nation to adopt DST. Britain was the second (a month later) and a number of other European nations quickly followed suit.

The United States adopted DST on March 19, 1918, also as a wartime measure to save electricity. More generally, DST was part of the Standard Time Act (P.L. 65-106), which created four distinct time zones – Eastern, Central, Mountain, and Pacific – as well as seven months of Summer Time or “War Time” (as it was known during World War I). From the start, interests lined up on both sides; farmers were opposed while the local chambers of commerce were in favor. Wartime pragmatism won out and the Standard Time Act passed with a huge majority (253-40) in the House and by voice vote in the Senate.

Following the end of World War I, farmers built up their lobbying organizations in Washington and used their influence to push for a repeal of the Standard Time Act’s DST provision. Without the wartime concern for saving energy, and despite opposition from President Woodrow Wilson, the organized farming interests won out. The House and Senate each passed the repeal legislation by large majorities (232-122 and 41-12). President Wilson vetoed the measure, but both chambers easily overrode him (223-101 and 57-19). DST was thus dead and would remain so at the Federal level for more than four decades, other than a short period during World War II – between 1942 and 1945 – when War Time was implemented again as an energy-saving measure.

In the post-war years, as Alan Burdick writes, “daylight saving was a free-for-all; cities, counties, and states could follow it on whatever schedule they liked, or not follow it at all.” As Table 1 indicates, in 1955, some of the largest cities in the U.S. had very different time schedules: two variants of DST, as well as regular year-round standard time. Consider a truck carrying goods from Atlanta to Boston. The driver would pass repeatedly back and forth through different time regimes, needing to reset his watch every other hour, without ever leaving his time zone.

Table 1. Time Observed in Major U.S. Cities, 1955

Daylight Saving Time Year Round Standard Time May through September May through October Baltimore

Cleveland

Los Angeles

Louisville

Montreal

St. Louis

Washington, DC Boston

Buffalo

Chicago

Hartford

New York

Philadelphia

Pittsburgh

Providence Atlanta

Birmingham

Cincinnati

Dallas

Denver

Detroit

Houston

Kansas City Memphis

Milwaukee

Minneapolis

New Orleans

Omaha

Salt Lake City

Seattle

Portland, OR

This decentralization created significant coordination problems. The communications and transportation industries were especially affected, and company executives were on the forefront of lobbying Congress for a new national standard. By 1965, DST was operating fully in fifteen states and partially in sixteen others. As Figure 1 illustrates, the Northeast was a full subscriber to DST, with much of the Mid-Atlantic, Midwest, and West partly on board. The traditional South, outside of Virginia, was the major holdout.

Figure 1: DST Policy by State, 1965

As more of the country was moving toward uniformity, members of Congress were as well. And President Lyndon Johnson was also supportive. Thus, in the 89th Congress (1965-66), multiple DST bills were introduced, and the issue was debated in earnest. Finally, Congress approved a measure that would institute DST for six months of the year, spanning the last Sunday in April through the last Sunday in October. While some opposition existed, the House passed the measure easily – approving the conference report 282-91 – while the Senate adopted it via voice vote. And on April 13, 1966, President Johnson signed the Uniform Time Act (P.L. 89-387) into law. DST was now a permanent fixture in the United States.

Since then, the parameters of DST have sometimes changed. The OPEC oil embargo of 1973-74 led Congress to institute year-round DST for a two-year trial period, as an energy-saving initiative. Not long after “Emergency DST” went into effect, public opinion began to shift against it. Parents of school-age children were upset that their children often had to leave for school in the dark. And when several children were killed in traffic accidents early in the winter, Emergency DST opponents blamed it on the legislation. In addition, early reports of energy saving were quite low, which disappointed supporters and made them question the efficacy of the legislation. The final straw was the end of the oil embargo, which OPEC lifted on March 18, 1974. As a result, Congress first scaled back the emergency DST measure and then allowed it to expire. The Uniform Time Act’s provisions were back in force.

In 1975, 1981, and 1983, congressional attempts were made to lengthen the period of DST, by changing the start or end dates. But they all failed. In 1985, another attempt was made, and this time there was considerable momentum for a change. For example, the business community – led by convenience stores, fast-food companies, makers of barbeque grills, and candy manufacturers – were part of a large DST lobbying coalition. And President Ronald Reagan also voiced support for a DST extension. After considerable wrangling, Congress extended the period of DST by three weeks, starting on the first Sunday of April (rather than the last Sunday of April) and ending on the to the last Sunday in October. This lasted until the end of the George W. Bush administration, when an additional extension was made. As part of the Energy Policy Act of 2005, DST was increased by roughly four weeks. It would now extend from the second Sunday in March through the first Sunday in November. The extension into November was pushed by candy manufacturers and concerned parents, who wanted one more hour of daylight to allow children to go trick-or-treating on Halloween.

Since 2007, then, DST extends from the second Sunday in March through the first Sunday in November. This is the prevailing status quo. Recently, state interests began forming on the issue – to potentially effect change.

Analysis

Gray and I conducted our analysis of the determinants of DST policy in Congress by collecting all roll-call votes in congressional history that were explicitly and primarily about DST, including final-amendment votes and final-passage votes. In total, there were 21 such roll calls. The first of these was in 1918 (the 65th Congress) and the most recent was in 1986 (the 99th Congress). We did not include votes for larger bills that may have tangentially affected DST (like the Energy Policy Act of 2005) or modified it as a minor provision of omnibus legislation. We also excluded purely procedural votes on DST-related bills that had no DST policy impact on their own.

For each of the 21 roll calls, we took the associated vote matrix using the Voteview system (https://voteview.com/) and stacked them into a single dataset organized with a member-vote observational unit.[3] Our dependent variable was Pro-DST Vote, which was a “1” when the member of Congress voted for the side that would result in the most expansive DST, and a “0” otherwise. For final-passage votes, we compared the proposal to the status quo. For amendment votes, we compared the proposed amendment to the underlying bill being amended.

As independent variables, we considered four different types of constituency-specific variables: ideology, partisanship, geography, and constituencies. For ideology, we included both First-and Second-Dimension Common Space DW-NOMINATE Scores. These are measures of revealed preferences, which are scaled based on all recorded roll calls across congressional history. The first dimension is widely seen as separating members based on their preferences regarding public intervention in the economy, with lower scores representing liberals who favor more public intervention and higher scores representing conservatives who favor less public intervention (see Poole and Rosenthal 2007). The second dimension likely captures urban/rural divides, which heavily overlapped with cultural and racial preferences at the times of these votes. Thus, for both dimensions, we expected higher scores to be correlated with reduced support for DST.

To measure partisanship, we included a dummy variable, Republican, which took the value “1” for members of the Republican Party and “0” otherwise. We expected that Republicans, being more consistently economically conservative, were less likely to support DST than Democrats.

Time and daylight also have a clear geographic component. Sunlight occurs first in the most eastern parts of the United States, moving west. This provides the justification for time zones. Within each time zone, this same pattern emerges and intersects with DST. The most western parts of any time zone are the ones where the sun will rise latest in local time. When DST pushes clocks forward, it has the greatest effect on these areas as sunlight will occur latest there. Some anti-DST advocates have argued that pushing time forward would mean that morning commutes for workers and school children would be undertaken in the dark, increasing risks for accidents. If this were true, the western parts of each time zone would be the parts most likely to be affected. It is possible that this concern for how strongly an area would be affected would filter into the intensity of constituent opposition and eventually into representative opposition. To assess this more systematically, we included a measure of Distance to Time-Zone Edge, which was the number of miles (in hundreds) from the centroid of the district (for representatives) or states (for senators) to the western edge of the centroid’s time zone.[4] These measurements were constructed using GIS shape files of historical Congressional districts and of time zones.

Finally, we considered the presence of a particularly organized and powerful constituency that strongly opposed DST: farmers. All historical evidence points to farmers representing the strongest opposition to DST. Thus, if members of Congress are responsive to their constituents, especially their politically organized and mobilized voters, they should be more likely to oppose DST the more farmers there are in their geographic unit. To assess this, we included Farmers’ Share of Population, or the number of farmers in a district or state as of the previous census divided by the total number of people in the district or state at the previous census. We multiplied this by 100 to provide a more appreciable percentage-point scale. Districts ranged from about zero percent farmers to about twenty percent farmers, though the average trended down considerably over time.

We estimated two logit models. Each model contained fixed effects for unique roll-call votes, plus the geographic and farmer variables. Model 1 included the ideological variables, 1st and 2nd Dimension NOMINATE Scores, while Model 2 included instead a Republican dummy variable. In each model, errors were clustered by individual member of Congress (MC), to correct for the correlation of vote choices across multiple votes by the same person. Results appear in Table 2.

Table 2. Vote Choice on DST Roll Calls in Congress, 1918-1985

Variable (1) (2) 1st Dimension NOMINATE -1.96**

(0.15) 2nd Dimension NOMINATE -1.57**

(0.13) Republican -0.50**

(0.10) Distance to Time Zone Edge 0.17**

(0.02) 0.20**

(0.03) Farmer % of Population -0.42**

(0.03) -0.49**

(0.03) N 5,402 5,402 Clustering Level MC MC Years 1918-1985 1918-1985 Clusters 1,746 1,746 “Pseudo” R2 0.40 0.33

*p<0.05, **p<0.01

More economically conservative members (1st Dimension NOMINATE Score) were considerably less likely to vote for DST expansion than more liberal members, holding other attributes fixed. A one-point increase corresponds to about a 26.5 percentage-point decrease in the probability of a pro-DST vote. The pattern for the second dimension is substantially similar. A one-point increase in the 2nd Dimension NOMINATE score corresponds to about a 21 percentage-point decrease in the probability of a pro-DST vote.

We also found that those in the western parts of their time zones were less likely to support DST, as expected. As the number of miles from the western time zone border increased, the likelihood of supporting DST also increased. In this case, every 100 miles of distance corresponded to about 2.3 percentage points of predicted pro-DST vote probability.

NOMINATE scores should incorporate information about constituents’ preferences, including those of farmers. Thus, the inclusion of farmers in our model tests for the specific impact of a highly agrarian constituency above and beyond how that agrarian constituency otherwise influences a member’s revealed preferences. Despite this conservative test, we still found strong, significant results. Each extra percent of the district or state made up by farmers is associated with a 5.6 percentage-point decrease in the likelihood of supporting DST expansion. Members from highly agrarian districts were extremely unlikely to support DST expansion.[5]

Since we analyze votes taken over more than sixty years with frequent, long gaps between votes, it is entirely possible – likely, even – that the relative impact of the different factors changed over time. This is further likely because the DST agenda changed over time as well. In the 1910s and again in the 1960s, DST questions were largely about creating DST and establishing a national standard for it. The votes of the 1970s and 1980s were largely about determining how much DST there would be, with its elimination rarely considered. To assess when our factors mattered and how much, we analyzed votes separately within each of the four decades featuring roll calls: the 1910s, 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. We then plotted the marginal effect of a one-standard-deviation increase in each variable within each decade. The results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Marginal Effect of a 1-SD Increase in Each Variable by Decade

Both the 2nd NOMINATE dimension and the percentage of farmers in a district were significant covariates of vote choice in each decade. The 1st NOMINATE Dimension and the distance to the western time-zone border only became significant covariates in the latter decades. The impact of geographic considerations appears to have increased over time. As the agenda switched from “whether?” to “how much?”, those most affected were more reluctant to expand it further. Also, over the same time that America became considerably less agrarian, between 1918 and 1985, the relative importance of farmers appears to have increased. Members of Congress from districts with large numbers of farmers in the 1980s were considerably less likely to support expansions of DST.

Conclusion

We found evidence that conservative members (and Republicans) have opposed expansive DST policy more than liberal members (and Democrats). But we also found that ideology or partisanship only go so far in explaining vote choice on DST. That is, members of Congress also strongly respond to and represent their local interests, controlling for ideology or party—members whose constituencies were more affected by DST due to geography were less supportive, while those whose districts or states contained sizeable farmer populations were also less supportive. The strongest consistent predictor of vote choice was actually a targeted constituency measure, the share of the district or state population made up by farmers, which outperformed general preference measures such as NOMINATE. Based on these findings, we believe DST voting in Congress across the 20th century was a quintessential example of meaningful constituent representation.

What is the future of Daylight Saving Time? Interestingly, the inconvenience of changing time twice a year has driven modern opposition to DST. And this has ironically led to new proposals. Recently, Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Representative Vern Buchanan (R-FL) introduced identical bills in the Senate and House to shift the country to year-round DST.[6] This throwback initiative (to the Emergency DST of the early-1970s) would solve the problem of time changes and remove DST from active consideration by effectively making it permanent.

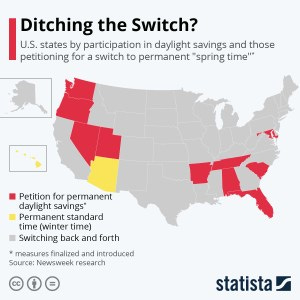

Other major figures in Congress, like Senators Patty Murray (D-WA) and Ron Wyden (D-OR), have lent their support, suggesting that year-round DST has some bipartisan support. While Congress considers whether to take action, however, a number of states are in the process of deciding for themselves. (States would need a federal exemption – like Arizona and Hawaii received in the late 1960s – to opt out.) A number of states are currently considering the move (see the figure from Statista below).

And even as different levels of government in the United States struggle with what to do with DST, foreign nations are also considering change. Recently, for example, the European Parliament voted to end DST in European-member nations by 2021. Thus, DST continues to be an important and contentious topic, and lawmakers at different levels of government in various nations will likely discuss policy options for some time to come.

UPDATE (November 4, 2022): I originally posted this piece on October 30, 2020. Since then, there have been happenings in Congress. On March 15, 2022, in a voice vote, the Senate unanimously approved the Sunshine Protection Act, which would make Daylight Saving Time permanent. If adopted into the law, the legislation would take effect in November 2023 and eliminate the process of changing clocks twice a year. While Speaker Nancy Pelosi said she supported making DST permanent, the House has so far failed to act on the legislation. And despite the Sunshine Protection Act having a lot of public support, there is no evidence that the House Democrats will make DST a priority in the waning days of the 117th Congress.

—

[1] Note that Arizona and Hawaii are the only states that do not observe DST. They received exemptions. See https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/arizona-us-daylight-saving-time-why-hawaii-sunlight-date-when-a8816481.html.

[2] We rely mainly on Downing (2005) and Prerau (2005) for the material in this section.

[3] Twice in our dataset, a roll call in the Senate matched a roll call in the House identically (the 1919 repeal of DST and the subsequent override of President Wilson’s veto), and so we combine these votes into a single bicameral roll call, reducing our total number of unique roll calls to 19.

[4] The centroid is the geographic mean location of the district. The distance is measured in the shortest straight line.

[5] For additional analyses that examine (a) within-party variation, (b) regional variation, and (c) the relative impacts of the variables, see our published article.

[6] On March 14, 2018, during the 115th Congress, Rubio and Buchanan first introduced the Sunshine Protection Act (S. 2537 and H.R. 5279). On the same day, Rubio also introduced the Sunshine State Act (S. 2536), which requested that Congress provide Florida for an exemption to go to year-round DST. In introducing S. 2536, Rubio was representing the Florida legislature, which voted overwhelmingly in support of year-round DST legislation (103-11 in the Florida House, 33-2 in the Florida Senate). In a press release, Rubio outlines a variety of potential, positive effects for the nation in going to year-round DST; see https://www.rubio.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/press-releases?ID=FE3C7A71-E17A-4406-8D2D-BD615C8D3694. S. 2537 and H.R. 5297 both died in committee. On March 6, 2019, during the 116th Congress, Rubio and Buchanan re-introduced the legislation (S. 670 and H.R. 1556).