When Democrats in Congress Tried to Ban Interracial Marriage

In 1891, the Federal Elections Bill – spearheaded by Rep. Henry Cabot Lodge (R-MA) – died in the Senate. This bill would have provided the federal government with new power to enforce African American voting rights in the South. Its demise was a devastating blow to the Republican Party, and also signaled the GOP’s last meaningful effort to promote Black civil rights until the early 1920s. For the next three decades, civil rights policy largely disappeared from the congressional agenda. African-American historian Rayford W. Logan has famously referred to these years as the nadir of Black experience in America.[1]

During this period, the Democrats returned to power under President Woodrow Wilson. They enjoyed unified control of government for six years, beginning in March 1913, and sought to use their leverage in a variety of ways. In Congress, they pursued policies that would undermine the rights of Black citizens. One of their goals was to ban interracial marriage, by enacting a federal anti-miscegenation law. Justin Peck and I document this Democratic initiative in our forthcoming book, Congress and the First Civil Rights Era, 1861-1918.

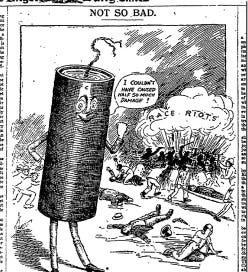

The Democrats would begin their quest during the lame-duck session of the 62nd Congress. On December 11, 1912, Rep. Seaborn Roddenberry (D-GA) proposed a constitutional amendment to prohibit interracial marriage. Roddenbery’s proposal came on the heels of significant racial unrest. Race riots had broken out throughout the country in recent years, due in part to the athletic success of Jack Johnson, the black boxing champion, who retained his title against Jim Jeffries, the white former world champion, in July 1910.

On its own, Johnson’s athletic triumph might have been too much for white Southerners to accept. Combined with Johnson’s marriage to two white women, Southern Democrats sprang into action. Roddenberry mentioned Johnson by name in his floor diatribe, condemning Northerners for allowing interracial marriage and thereby – in his mind – making possible Johnson’s racially subversive behavior.[2]

Roddenbery hoped to goad Congress into forcing Southern views of interracial relationships onto the rest of the nation. He noted that legislatures in 29 of the 48 states had already passed anti-miscegenation laws, while eleven other states were considering them. (See the map below.) With this in mind, Roddenbery claimed that the proposal would simply codify a practice that was already accepted by much of the country. In the end, his proposal went nowhere, as it was referred to the Judiciary Committee where it died. Moreover, only one additional state – Wyoming in 1913 – would enact an anti-miscegenation law.

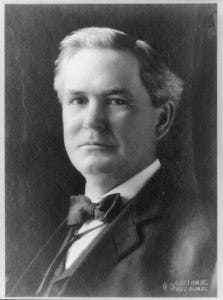

The issue would emerge again in the lame-duck session. On February 10, 1913, Rep. Thomas Hardwick (D-GA) introduced legislation to “prohibit in the District of Columbia the intermarriage of whites with negroes or Mongolians” and make it a felony – with a penalty of up to $500 and/or 2 years in prison. Democratic opponents of interracial marriage had thus narrowed the scope of their attack. Rather than pushing a constitutional amendment, they sought simply to ban interracial marriage within the District of Columbia.[3] Somewhat surprisingly, Hardwick’s anti-miscegenation bill was passed in less than five minutes – by simple division vote – with no debate.

In explaining the outcome and lack of debate on the bill, a correspondent for the New York Times reported: “Almost every State has a law prohibiting such marriages, and the feeling generally among House members is that the Nation’s capital should be in line with the general sentiment of the States on this subject.”[4] Thus, House Republicans, perhaps intimidated by the Democrats’ bluster and worried about shifting public opinion and further state-legislative activism in the North, quietly acquiesced and allowed the bill to pass. In the end, nothing would come of the legislation, as it was referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee – controlled by Republicans – and not reported out before the session expired less than a month later.

Just two years later, during the lame-duck session of the 63rd Congress, Democrats – now with majorities in both chambers – again pushed anti-miscegenation legislation in the District of Columbia. This bill, offered by Rep. Frank A. Clark (D-FL), was even more draconian than the 1913 version. It sought to ban interracial marriage and impose a penalty of up to $5,000 and/or 5 years in prison. Clark’s anti-miscegenation bill was considered on January 11, 1915, and unlike the Hardwick bill two years earlier, elicited a short discussion. Clark argued that enactment of his bill “was in the interest of both of the races.” He contended that maintaining racial purity was paramount, because “the future of the world is dependent upon the preservation of [the White race’s] integrity.”

Rep. James Mann (R-IL) spoke for the Republican side, stating that while he opposed interracial marriage, he also opposed making such marriages a crime. Moreover, Mann articulated what he believed to be the intent of the legislation: “The purpose of this law is to further degrade the negro, to make him feel the iron hand of tyranny so long practiced against his race.” After a few more brief remarks, the previous question was ordered, and it carried, 175-119; Mann quickly moved to recommit the legislation to committee, which failed, 90-201; and Clark’s anti-miscegenation bill was then passed 238-60.

Whereas the Hardwick bill was adopted via a simple division vote, the Clark bill elicited three roll calls before an outcome was achieved. What explains these differences? There is considerable evidence that pressure from Black citizens – newspaper editorials along with individual and group initiatives – increased after the passage of the Hardwick bill and ramped up considerably after Clark re-introduced the miscegenation issue. For example, a number of public meetings were scheduled post-Hardwick, to insure that additional segregationist legislation would meet active resistance. And groups like the Independent Equal Rights League, led by civil-rights luminaries like Ida B. Wells, lobbied individual House members during Clark’s anti-miscegenation mission. Thus, Black voices had raised the visibility of the issue and the stakes in Washington, which forced members of both parties to reveal – through public statements and recorded roll-call votes – their preferences to their constituents.

All three roll calls were cross-regional party votes: a majority of Northern Democrats joined with all Southern Democrats against a majority of Republicans.[5] However, some interesting variation appears within the two parties. Roughly a quarter of Northern Democrats opposed shutting off debate on the bill; this opposition largely melted away across the remaining two votes.[6] And while Republicans were nearly unanimous in opposing the initial previous question motion, GOP solidarity crumbled thereafter. On the final-passage roll call, nearly half (40 of 90) of the Republicans defected and voted in favor of the anti-miscegenation legislation.

GOP voting on the final-passage roll call can be broken out further based on type of state represented. More than half of Republican votes in favor (21 of 40) came from members who represented states with an anti-miscegenation law on the books. In total, a majority of House Republicans from states with anti-miscegenation laws (21 of 27, or 77.8%) voted for the legislation, while only a minority of House Republicans from states without anti-miscegenation laws (19 of 63, or 30.2%) supported it. Thus, when push came to shove, many Republicans eschewed the party’s historical connection to Black voters and focused on representing the (anti-miscegenation) interests of the Whites who elected them.

This electoral-connection story can be seen in more detail by examining Republican vote choice statistically. As the regression table below indicates, the typical variables we associate with explaining congressional voting – members’ ideological preferences – are not significant predictors on the final-passage roll call. A strictly ideological model – with two NOMINATE scores as the sole independent variables – provides no leverage in explaining GOP votes.[7] Only when a variable is added to account for whether a state had an anti-miscegenation law in place does the model begin to explain individual vote choices. Finally, whether a state’s legislature was considering an anti-miscegenation law did not matter in terms of explaining GOP vote choice; a variable capturing this provides no additional explanatory leverage (and actually results in a model that performs less well).[8]

Logit Analyses of GOP Votes on Anti-Miscegenation Legislation, 63rd Congress

(1) (2) (3) NOMINATE 1 0.46

(2.70)

2.60

(3.02)

2.09

(3.14)

NOMINATE 2 0.14

(0.54)

-0.26

(0.63)

-0.05

(0.67)

State Law 2.32***

(0.57)

1.71*

(0.84)

Law Introduced -0.67

(0.74)

Constant -0.43

(1.14)

-1.91

(1.28)

-1.19

(1.50)

N 90 90 90 LR χ2 0.07 16.81*** 17.28** % Correctly Predicted 55.6 72.2 70.0 PRE (naïve model) 0 0.375 0.325

Note: Logit coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. Baseline model for Proportional Reduction in Error (PRE) calculation is a naïve (minority-vote) model.

*p< .05, **p< .01, ***p<.001

On January 12, 1915, the Senate received the bill and referred it to the Committee on the District of Columbia. Despite the Democrats’ control of the committee, the bill was never reported out before the lame-duck session ended. Thus, the House Democrats’ actions were for naught. While a symbolic victory was achieved – and electoral “points” were no doubt scored in the South and some parts of the North – federal anti-miscegenation policy was not produced. And the Democrats would not again try to push such legislation in Congress.

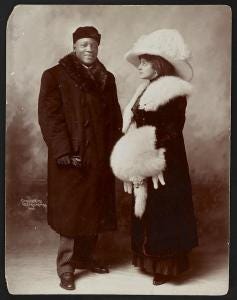

In the aftermath of the Democrats’ failed efforts, some states would eventually reverse course and repeal their anti-miscegenation laws. But by the mid-1960s, seventeen states – those that imposed Jim Crow – still had anti-miscegenation laws on the books and enforced them. As a result, the District of Columbia would continue to be a haven for interracial couples in the South who wished to marry. Indeed, Mildred and Richard Loving – the Black-White couple pictured at the top of this post, who would be at the center of the Loving v. Virginia (1967) Supreme Court case that struck down state-level anti-miscegenation laws – were married in the District of Columbia in 1958.

[1] See Rayford W. Logan, The Betrayal of the Negro: From Rutherford B. Hayes to Woodrow Wilson (New York: Da Capo Press, 1997).

[2] For more on the connection between Jack Johnson and anti-miscegenation laws, see Peggy Pascoe, What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 163-73. Johnson was also later prosecuted under the Mann Act. This law, enacted in 1913, sought to punish the transport of women across state lines “for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.” It became a tool for enforcing the spirit of anti-miscegenation legislation even though Congress failed to enact a formal prohibition on interracial marriage. For more on the Mann Act see, David J. Langum, Crossing Over the Line: Legislating Morality and the Mann Act (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994). On May 24, 2018, President Donald Trump issued a posthumous pardon for Johnson. See https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/24/sports/jack-johnson-pardon-trump.html.

[3] Article 1, Section 8, Clause 17 of the Constitution gives Congress explicit jurisdiction to govern on matters involving the District of Columbia.

[4] “To Forbid Race Intermarriage,” New York Times, 2/11/1913, 7. In addition, the continued influence of boxer Jack Johnson on the Southern mind was apparent in an editorial in the Charlotte Daily Observer: “Passage through the National House of Representatives of a bill prohibiting intermarriage of whites with negroes, Chinese, Japanese or Malays in the District of Columbia is the latest evidence of the good which the abominable Jack Johnson case brought forth” (2/13/1913, 4).

[5] On the previous question vote, Northern Democrats voted 77-26, Southern Democrats 96-0, and Republicans 2-89. On recommital, Northern Democrats voted 11-88, Southern Democrats 0-99, and Republicans 76-13. On final-passage, Northern Democrats voted 95-7, Southern Democrats 102-0, and Republicans 40-50. (Remaining votes were cast by four Progressives.)

[6] Why this small group of Northern Democrats opposed shutting off debate is unclear. One possibility is that they wanted more time to debate the issue and “position take” (or grandstand). That is, they wanted to be able to go on the record with public statements, for their constituents’ benefit and consumption, and this could not happen if debate was shut off (in their minds prematurely).

[7] For more on NOMINATE, see Keith T. Poole and Howard Rosenthal, Ideology and Congress (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2007); Phil Everson, Rick Valelly, Arjun Vishwanath, and Jim Wiseman, “NOMINATE and American Political Development: A Primer,” Studies in American Political Development 30 (2016): 97–115.

[8] The first- and second-dimension NOMINATE scores are not statistically significant in any of the three vote models. When a state-law variable is added (model 2), it is positive and statistically significant – as votes in favor of the legislation are positively associated with representing a state with an anti-miscegenation law in place – and the percent of GOP votes correctly predicted increases from 55.6 percent to 72.2 percent. Finally, when a variable is added to indicate whether an anti-miscegenation law was introduced in a state’s legislature, it is not statistically significant and the percent of GOP votes correctly predicted decreases from 72.2 percent to 70 percent. The latter result is perhaps not surprising, as the momentum for anti-miscegenation laws stalled by 1913. Wyoming adopted a new law that year, but none of the other states did – or in later years. Thus, while legislation in those states may have been introduced, there was not a significant push for change. As a result, Republican House members from those states were not influenced.