Yesterday, we provided some thoughts before the speakership balloting to the 118th Congress took place. It turned out to go more than one ballot — three ballots, in fact — something we’ve not seen in a century. Here are some thoughts about what has occurred and what is likely to unfold, from the perspective of the history of contentious speakership elections, as detailed our book, Fighting for the Speakership.

1. The fight is an odd one in the history of speakership contests, because the dissident faction isn’t “moderate” with reference to the overall political space. (Think about Joe Manchin and Lisa Murkowski in the Senate.) The 1923 battle, for instance, featured progressive Republicans battling with the conservative establishment over getting measures to the floor they believed would win if given the chance, because Democrats would back them. The fallback position for the progressives was, “if you don’t make a deal with us, we’ll just vote with the Democrats to organize the chamber.” The threat was theoretically plausible. This framed the bargaining within the party in terms of whether the dissident faction would do better with the Republicans or Democrats. Frederick Gillett (R-MA), the presumptive Speaker, had every reason to negotiate.

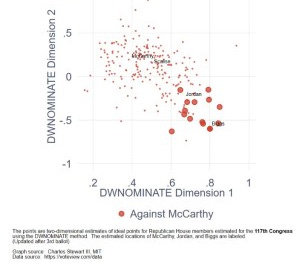

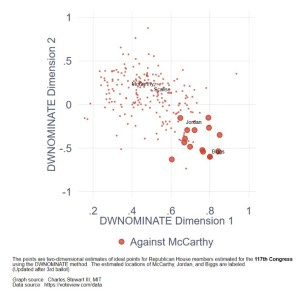

That’s not what we have now. The bargaining situation is illustrated nicely using the DW-NOMINATE metric developed by Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal, which allows us to plot the “ideal points” of House members in a two-dimensional space. For the previous Congress, the left-right dimension was the traditional liberal-conservative dimension; the up-down dimension was establishment vs. rebel.

The following graph shows the estimated ideal points of all Republicans in the last Congress. The large data tokens are the ideal points of the Republicans who voted against McCarthy for Speaker on the 3rd ballot. The locations of McCarthy, Jordan, Biggs, and Steve Scalise are highlighted. (Scalise comes into the story in a bit.) Note that all the dissidents are in the lower right of the plot—far-right in conventional terms and highly anti-institutional. Andy Biggs (AZ) is a pure play among this group. Jim Jordan (OH) is on the boundary.

What leverage do these members have? Democrats are all to the “left” of this graph. They aren’t going to join with them. To be credible, the 20-or-so dissidents have to be pursuing something that is outside conventional policy. (We’ll return to this.)

The closest historical parallel is the Speakership election of 1849 (31st Congress) when the Whigs held a plurality but were a couple of seats short of a majority, with the caucus split over taking a stand on slavery in the territories. A small group of southern Whigs bolted the party. They were termed the “Impracticables,” because they refused to bargain over organizing the House and insisted on protecting the rights of slaveholders. We spend almost an entire chapter of our book reviewing this episode.

The bottom line is that after 59 ballots and several weeks of deadlock, the House decided to – after trying three more regular ballots – elect the speaker by plurality, not a majority. Otherwise, the House never would have organized.

2. McCarthy is battling dissidents within his party, but in terms of sheer numbers, he’s not facing the greatest degree of dissent of a party leader over the past decade. This is illustrated in the following table, which shows the breakdown of votes for Speaker from 2011 to the first ballot on Tuesday. Note that Boehner faced more dissidents in 2015, yet the margin over the Democrats was large enough that he was nonetheless able to gain election on the first ballot.

Just as important, note that this is the first time since 2009 (which is not shown in the table) in which all Democrats voted for a single Speaker candidate. Pelosi faced serious challenges to her leadership throughout her speakership—to the point that to gain election in 2019, she had to promise to limit her service to two terms. Despite her rocky hold on power, she always prevailed, and she never had to endure the embarrassment that McCarthy is going through. Why?

There are two important differences. First, for most of her leadership, her dissidents were to the right of the party. Again, as in 1923, they had a plausible exit strategy, so Pelosi had to take them seriously. But—and this is a point being missed in a lot of discussions right now—her dissidents wanted things she could deliver. And she did. Member by member, she bought off the opposition, counting the votes to 218.

McCarthy doesn’t have that luxury. His opponents don’t worry so much about gridlock. Legislative deal making is the problem.

3. What to expect on Wednesday? Part of the answer depends on what happened Tuesday night which, as of this writing, we don’t know. If the sides have dug in, then Wednesday could be like Tuesday.

4. What to expect beyond Wednesday? At present, there appear to be equally likely scenarios. The first is what we speculated about yesterday: the House Freedom Caucus can’t do what it cares most about—investigate the Biden Administration and family—until the House organizes. Thus, it won’t take much to get a sufficient number of defectors to come back to McCarthy, especially if he makes a symbolic gesture in their direction. The second scenario comes into play if the HFC become the modern version of the Impracticables. If it does, then McCarthy has two choices. The first is the historic one—he makes a deal with the Democrats to change the rules to allow the speakership to be decided by plurality. The second is to fall on his sword, designate Scalise the compromise candidate, and retire to the back benches as an elder statesman. At the moment, we still are betting that McCarthy becomes Speaker, but in a weakened form. But, the idea of Scalise as the Speaker becomes more and more attractive.