African Borders: Neither Random Nor Decided at the Berlin Conference

By Jack Paine (Emory University), Xiaoyan Qiu (Washington University in St. Louis) and Joan Ricart-Huguet (Loyola University Maryland

“I’ll show your paper to my dad, he’ll be really interested.” -Franco-Guinean economist

“This is going to be a classic in this literature! I have been teaching it since before it was published!” -Tanzanian political scientist

“You should really write this for a general audience.” -American World Bank employee

These reactions from individuals with disparate backgrounds share an important commonality—they, like us, had learned in high school that Europeans drew African borders arbitrarily at the 1884–85 Berlin West Africa Conference.

Our recent article in the American Political Science Review overturns two important pieces of conventional wisdom about border formation in colonial Africa. First is the claim that borders in Africa were decided at the Berlin Conference, or the broader notion that Europeans knew very little about conditions on the ground when they determined African borders. Second is the persistent idea that African borders are “as-if random,” that is, arbitrary with respect to realities on the ground.

Historians of Africa have long rejected the idea that the Berlin Conference was a seminal event in African border formation. Katzenellenbogen states succinctly, “It didn’t happen at Berlin.” He concludes, “the much vaunted Berlin Conference did not really accomplish much,” other than creating the Congo Free State (contemporary Democratic Republic of the Congo). Notable Francophone historians such as Pierre Boilley concur: “The cliché of Berlin has endured, in spite of efforts of historians to destroy it.” The still-leading historical account of the Berlin Conference, written by S.E. Crowe in 1942, provides extensive detail to substantiate how little the conference accomplished.

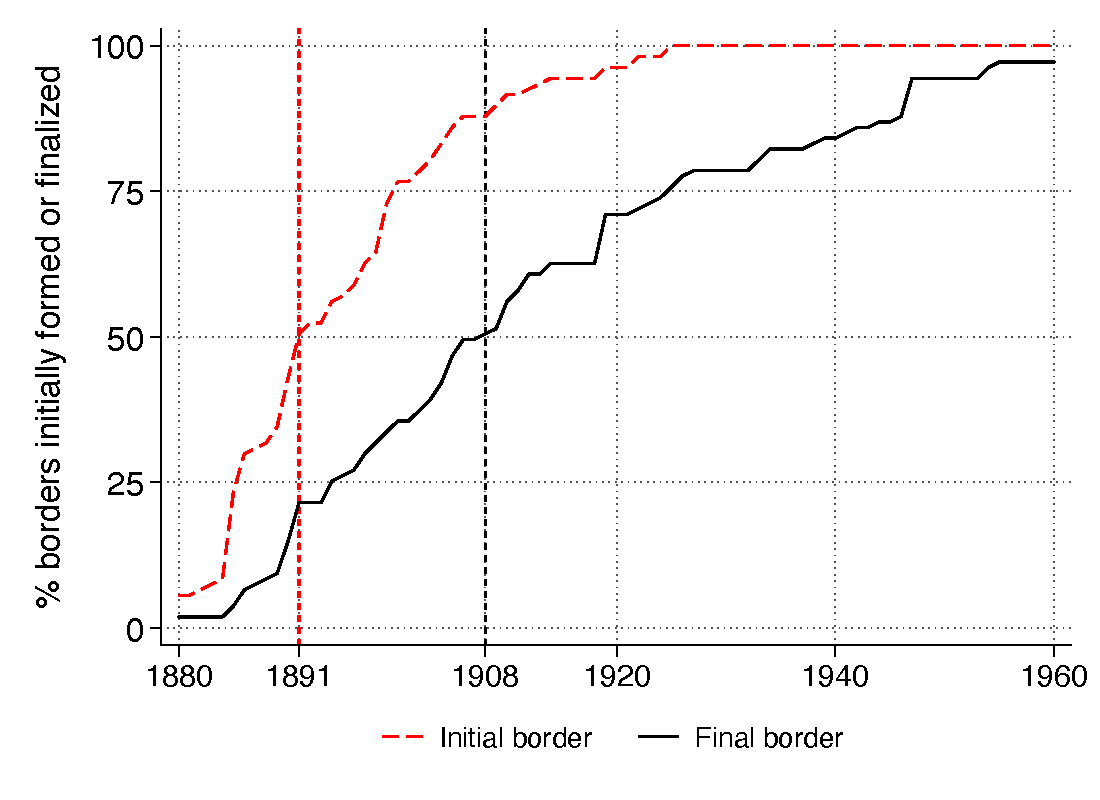

Nonetheless, the imagined importance of the Berlin Conference remains a “stubborn myth” (in the words of historian Paul Nugent) among non-specialists. We provide systematic data consistent with the minority of scholarship arguing against the myth of Berlin. The Berlin thesis simply doesn’t match the facts, as we demonstrate using originally compiled data summarized in Figure 1. For all 107 bilateral borders in Africa, we assessed the year in which a preliminary border originated and the final year in which a major revision happened. Half of Africa’s international borders did not exist in any form until 1891, six years after the Conference concluded. Moreover, half the borders were modified in major ways after 1908—more than two decades after the Conference concluded. The events surrounding the Berlin Conference occurred at the beginning rather than the end of the process that yielded Africa’s contemporary international borders.

If it didn’t happen at Berlin, then when and how did it happen? Some common notions are indeed correct. Europeans knew little about conditions on the ground in most parts of Africa at the time of the Conference in 1884–85. And they were self-interested with little regard for the people over whom they sought to claim control.

However, to make concrete and compelling territorial claims, Europeans had to learn facts about on-the-ground realities. This is the core premise of our alternative theoretical account, which helps to explain why border formation in Africa was in fact a dynamic and protracted process that took into account local features. This insight rejects a second common idea about colonial African states: the borders (most of which have persisted to the present day) are largely as-if random.

Europeans sought to minimize prospects for violent conflict among themselves as they conquered Africa. Achieving this goal required the powers to create shared expectations about how they would claim pieces of territory and how other powers would validate these claims.

One commonly accepted rule was the principle of suzerainty: a power that signed a recognized treaty with an African ruler gained all the territory within that ruler’s domain. This principle helps to explain why Europeans signed a flurry of new treaties with African chiefs following the Berlin Conference. The principle of suzerainty also encouraged using historical frontiers as guides for borders, rather than partitioning precolonial states.

Europeans’ need to gather information also enabled African rulers—who had greater knowledge of their claimed domains—to influence the location of borders. European imperial agents and African leaders each had incentives to overclaim. This produced a competitive process whereby Europeans renegotiated borders over time as they gathered information to support their territorial claims.

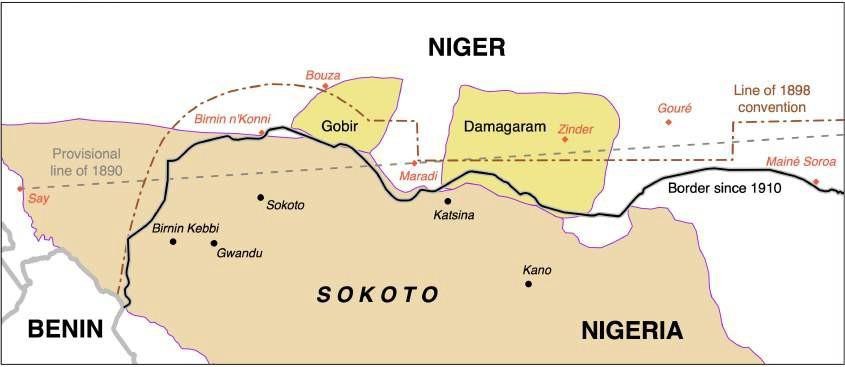

For example, the original division between British and French territories in today’s northwestern Nigeria was an arbitrary straight line drawn in 1890. Via a competitive process, the powers redrew the border in 1898 and again in 1904 because each side leveraged local political realities to press their territorial claims.

Water bodies, in particular major ones, were also important to the process of claiming territory. Long rivers facilitated trade and communication. In some cases, one European power had sufficiently intensive interests in controlling a particular river and its surroundings that it risked war to uphold a monopoly over access, as the British did when the French sought to gain control of the Upper Nile in 1898 (Fashoda Incident). However, more commonly, rivers provided a natural feature to divide spheres of influence. This would allow both powers to gain the advantages associated with river access.

The powers approached major lakes similarly as major rivers. As Figure 2 illustrates, the borders throughout the Great Lakes region are inexplicable without referencing the lakes and precolonial states; these were the main foci of European negotiation in the area.

To systematically test our theory, we performed two empirical exercises. Collectively, they yield an unambiguous finding: Africa’s borders were not drawn in a random, haphazard way. History and geography were much more influential than most people realize—and certainly more than anyone has previously shown across a broad sample.

Our first empirical exercise assesses correlates of border location. Finding systematic local patterns would counter existing findings, such as Michalopoulous and Papaioannou’s statistical evidence that almost all local features of ethnic groups are uncorrelated with ethnic partition. We are agnostic about the most appropriate unit of analysis, so we instead divide the continent into 0.5ºx0.5º grid cells, numbering over 10,000 in total. We identify whether each cell contains a border segment (the outcome) as well as any local characteristics (explanatory variables), focusing mainly on precolonial states, rivers, and lakes.

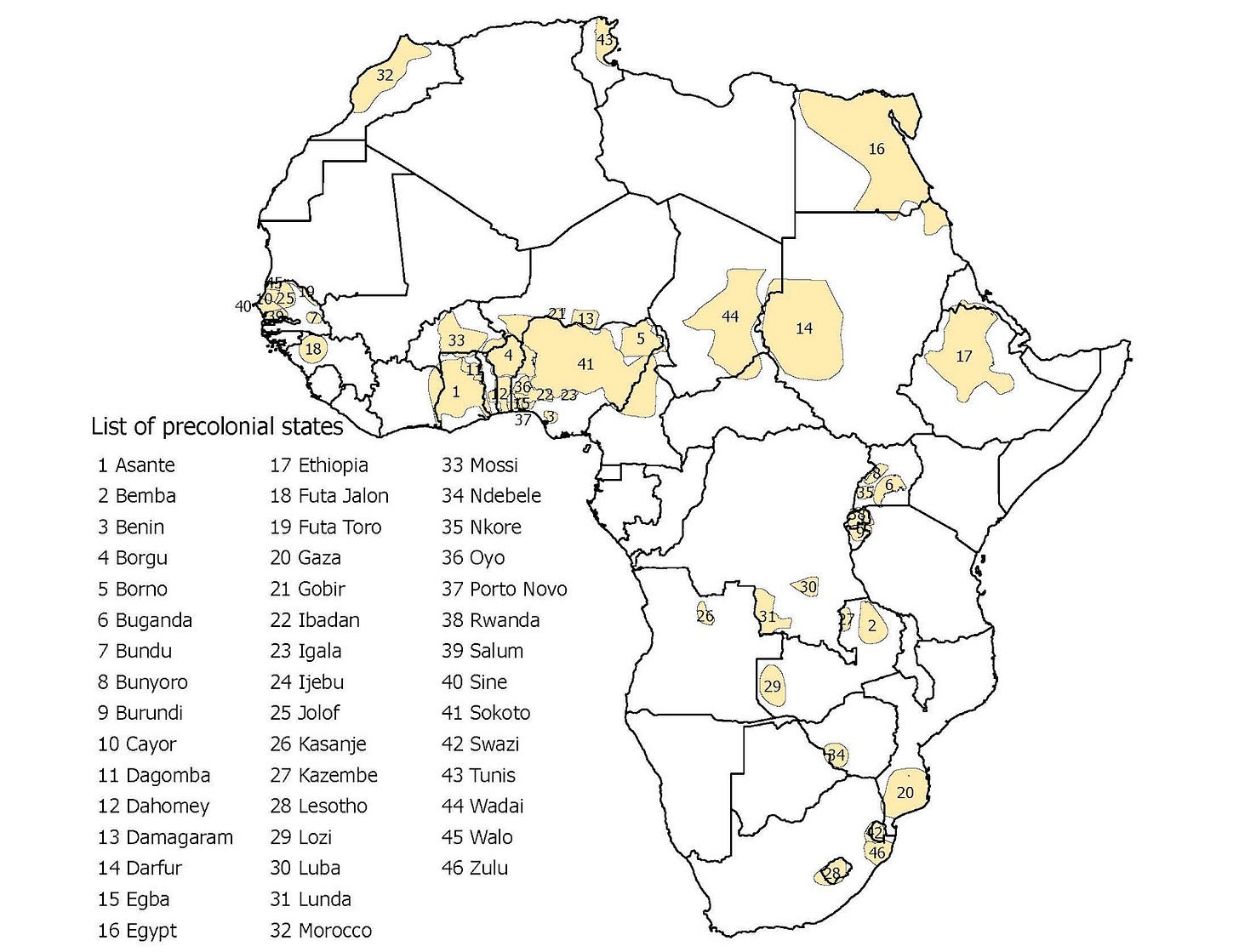

We used existing GIS data for geographic factors but compiled our own data on precolonial states. The commonly used Murdock ethnic polygons and codings of precolonial institutions are measured too inaccurately to yield credible findings, as we discuss in our main appendix. Instead, using historical atlases and numerous historical and anthropological sources on particular states, we identified a more accurate list of precolonial states in the mid-19th century —prior to European imperial expansion—and digitized their associated landmasses. We also accounted for potential imprecision in their frontier zones through extensive robustness checks.

In Figure 3, we map the location of the precolonial states in our dataset along with contemporary borders. A cursory examination suggests that the two are strongly associated. Maps of rivers and lakes yield a similar conclusion (e.g., Figure 2).

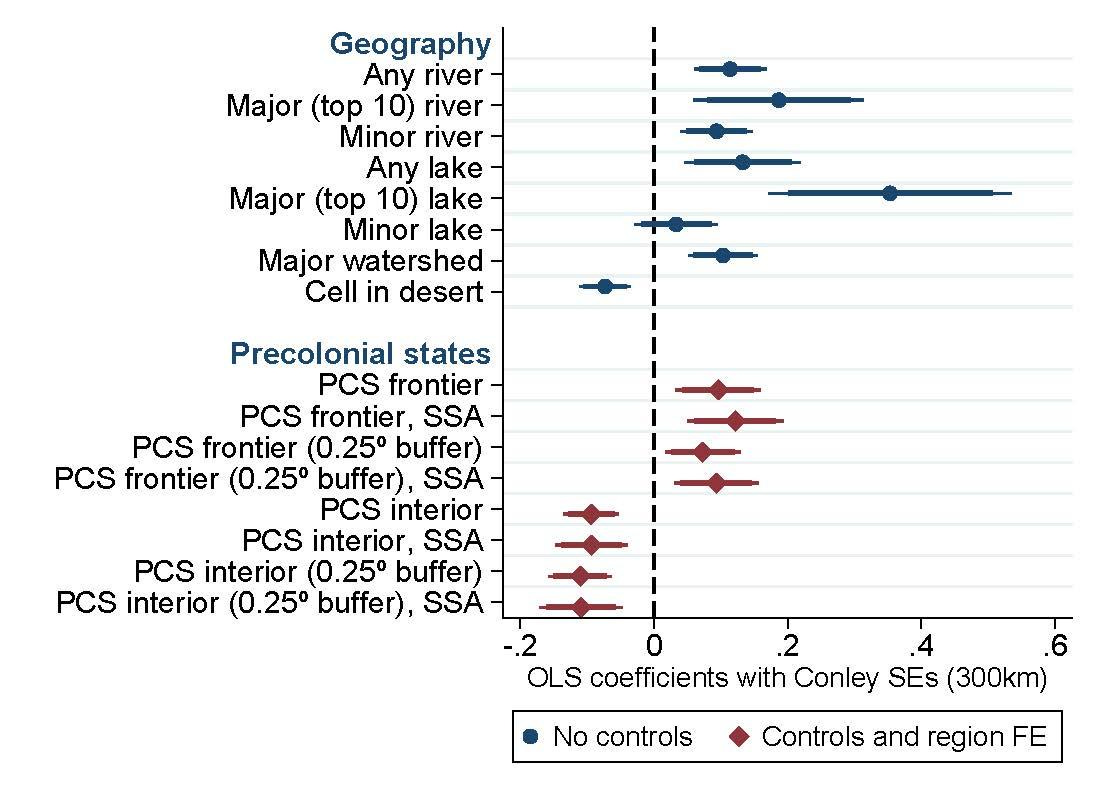

Moving from visual intuition to regression analysis, we find that the frontier zones of precolonial states correlate positively with the location of borders whereas the interior areas of precolonial states correlate negatively (see Figure 4). This supports our claim that European powers used the frontiers of precolonial states to draw borders but rarely partitioned these states. Importantly, this finding does not contradict the well-documented fact that many decentralized groups were partitioned across international borders (see, for example, Asiwaju, Miles, and Michalopoulos and Papaioannou). Our finding is more specific: ethnic homelands were not partitioned in an as-if random manner because the precolonial states were largely spared. Finally, we also show that rivers and lakes are strongly and robustly correlated with the presence of borders.

These systematic relationships provide clear evidence that the partition of Africa was not an as-if random process. But in fact our initial insights into this project were based not on quantitative patterns, but instead on the many cases we had studied in which historical and geographical features seemed essential for the formation of particular borders. As one example, Anene’s masterful The International Boundaries of Nigeria, 1885–1960 discusses the pivotal role of Yoruba states in shaping the southern portion of the Nigeria–Benin border, and the key influence of the Sokoto Caliphate’s frontiers on what became the Nigeria–Niger border (we illustrate the latter in Figure 5).

To move from possibly cherry-picked examples to a systematic sample, we examined the history of all 107 bilateral borders and systematically traced how each originated and changed over time. We provide extensive supporting details in our lengthy online appendix.

We compiled three pieces of information about each bilateral border. First, we measured the timing of initial border formation and all major revisions, as summarized earlier in Figure 1.

Second, we assessed whether historical political frontiers directly affected the location of each border. The answer was a resounding yes. In 62% of bilateral borders, Europeans settled a border in accordance with the location of African precolonial states, non-European states (e.g., Ottoman Empire), earlier white settlements, or (more rarely) migration zones of nomadic groups.

Third, we assessed the actual components of each border. Across the continent, rivers and lakes (or their watersheds) are the primary feature of 63% of bilateral borders—meaning that feature comprises the largest proportion of the border’s length (Table 1). Major water bodies alone (including the ten longest rivers and ten largest lakes, and their watersheds) are the primary feature of nearly one-quarter of borders.

By contrast, we find that straight-line borders are less prevalent than often claimed. Scholars commonly cite claims suggesting that anywhere from nearly half to upwards of three-quarters of African borders consist primarily of a straight line. We instead find that straight lines (counting both latitude/longitude lines and non-astronomical lines) are the primary feature of 37% of borders. Furthermore, most straight-line borders are concentrated in remote, sparsely populated areas like the Sahara Desert.

In sum, these findings dispel two common, related myths: (1) African borders were largely determined in a German boardroom, and (2) the resultant borders are located as-if randomly with regard to local political history and geography.

One particular implication of interest for scholars of HPE is that African borders do not constitute the type of natural experiment often suggested. The division of peoples across certain borders may have elements of as-if randomness. Examples include the since-eliminated divide between Southern British Cameroons and French Cameroon, discussed by Lee and Schultz, and the straight border between Kenya and Tanzania. However, we cannot assume that borders are located arbitrarily in general, or even that all straight-line borders are. For instance, some straight-line borders in the Sahara reflect the homelands of different Tuareg subgroups. In this sense, we add to the chorus of political scientists who explain the potential pitfalls of using borders as natural experiments, either in Africa (McCauley and Posner) or elsewhere (Kocher and Monteiro, Dunning, Malesky and Nguyen).

Collecting and analyzing a systematic sample of observations is a hallmark of quantitative social science research. But, especially in the realm of HPE, this approach complements efforts to trace historical causal processes, which insights from game theory also inform. In our case, such strategic and rational thinking makes sense of how Europeans settled territorial claims among themselves and with Africans. By combining these approaches, our article showcases the benefits of methodological pluralism, which we believe should be a core feature of HPE research.

Authors

Jack Paine: Associate Professor of Political Science at Emory University. He earned a Ph.D. in Political Science at UC Berkeley. His interests include the politics of authoritarian survival (with a focus on power sharing), consequences of Western colonialism for political institutions, and applied game theory. His recent book published with Cambridge University Press examines the origins and consequences of elections across the colonial world.

Xiaoyan Qiu: Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Washington University in St. Louis. She earned a Ph.D. in political science at the University of Rochester in 2021. Her research explores how international and domestic factors shape conflict behaviors in interstate and intrastate conflicts, focusing on belligerents' strategies, external support for insurgents, and the historical roots of contemporary conflicts.

Joan Ricart-Huguet: Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Loyola University Maryland. He earned a Ph.D. in Politics at Princeton University and was a Postdoctoral Associate and Lecturer at the Program on Ethics, Politics, & Economics at Yale University. His research interests include political elites, colonial investments and their legacies, education, and culture, with a focus on Africa. His book project shows that education and competence are fundamental to understand African cabinets since independence from colonial rule. This is in contrast to dominant explanations, which have focused on ethnic demography, conflict, and money in politics.

Hey! I’m Ghanaian-American and just read the piece on African borders—great read overall. I write about individual African countries myself, but with a different lens than many African writers who often lean heavily anti-Western or leftist. I try to call it like it is—highlighting both internal and external factors, especially economic dysfunction and leadership failures.

There’s a lot I believe your article gets right. I completely agree that African borders weren’t simply drawn by Europeans in some German boardroom during the Berlin Conference. As you note, many borders were drawn after the conference, and yes—European powers often relied on treaties of suzerainty with local rulers to legitimize their claims. Countries like Rwanda, Burundi, Dahomey, Lesotho, Botswana, Eswatini, Tunisia, and Algeria make that case well. I also appreciated the nod to arbitrary constructs like the Congo Free State (now the DRC), and the influence of rivers in shaping some borders (like Gambia-Senegal).

But where I take issue is with their broader conclusion—that African borders weren’t arbitrary or random at all. That’s a stretch. Once you dive into the precolonial history of individual African countries—kingdoms, empires, chieftaincies, and tribal boundaries—it becomes clear just how mismatched many modern states really are. A few examples:

1) Morocco:

Morocco historically claimed significantly more territory than its current borders reflect, which explains ongoing disputes like Western Sahara and past conflicts like the Sand War with Algeria over Western Algeria in the 1960s. Also after independence, Morocco originally claimed all of Mauritania and Northern Mali (the Azawad region where Tuareg nomads live).

2): Libya:

Libya is an ancient name but the borders of Libya are arbitrary. Libya is a modern construct combining Tripolitania (Ottoman-backed city-state), Cyrenaica (ruled by the Senussi order), and the Fezzan desert. These were unified only after Italy defeated the Ottomans. That’s not a natural nation-state—that’s a colonial patchwork.

3): Nigeria:

Perhaps the clearest case of arbitrary borders.. It combined several distinct precolonial entities—Hausaland, Kanem-Bornu, the Sokoto Caliphate, the Edo Benin Kingdom, the Arochukwu confederacy, the Nri Kingdom, the Oyo Empire, and more—into a single country whose boundaries clearly ignored historical realities.

Hausaland is also part of Southern Niger, Kanem-Bornu was also in Chad, the Sokoto Caliphate also had territory in modern day Cameroon, and parts of Burkina Faso and Niger. The Oyo Empire encompassed parts of modern day SouthWest Nigeria and Benin. This is why Hausas are in Niger & Nigeria, Fulani are in Nigeria, Cameroon, Burkina Faso and frankly all across West Africa, and Yorubas from Oyo are in Nigeria & modern day Benin.

4) Kenya & Tanzania

Neither existed pre-colonialism. The coasts had Swahili-Arab city-states like Mombasa, Zanzibar, and Kilwa who took slaves to the Arab World; the interior was sparsely populated with tribal chieftaincies like the Kikuyu, Maasai, Luo, Kalienjin, Chagga, Hehe and more. European borders pulled together vastly different ethnic groups with little shared history.

5) Uganda

The British allied with the Buganda Kingdom and used them (and the Maxim gun) to dominate rival statelets like Bunyoro and Ankole. Uganda wasn’t a historical nation—it was built through selective colonial alliances.

6) Sudan

Originally carved out by Mehmet Ali, the Albanian Turk who ruled Egypt. Sudan combined the Funj and Darfur, and various southern tribes south of the Sudd Swamp like the Dinka and Nuer. The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium later had a deeply divided North (Arab-Muslim) and South (animist-Christian), eventually leading to South Sudan’s independence in the 2010s.

Some interesting nuances that fit both our points (my point being arbitrary tribes being split and your point about countries made by geography like rivers) entail Senegal-Gambia. Ethnically the exact same people exist in both countries but they are split by the Gambia river, so Gambia exists inside Senegal.

Regardless, I could go on—Eritrea’s separation from Ethiopia due to Ottoman and then Italian influence, Namibia’s creation of many tribes by the Germans, the history of South Africa's borders and so forth. If you studied each country's individual history, there's no way you would make the conclusion that most borders aren't artificial based on their pre-colonial state.

Even in Ghana, my own country, borders do not neatly reflect historical realities. The Asante Empire, often cited as Ghana’s historical precedent, extended into territories now part of Togo and Ivory Coast after the Asante conquered the Gyaaman, while Ghana itself incorporates diverse northern kingdoms like Gonja.

So while you provide solid evidence that some African borders were indeed shaped by local geography, that some states were indeed protectorates as I mentioned, and that many states were made post Berlin conference, your sweeping conclusion that this process wasn't random or arbitrary or that maps onto historical states doesn't hold up when you dive deeper into specific national histories and see how tribally mismatched many countries are.

Thanks for sharing this! Really interesting analysis. Though I wonder if the foil for the argument – the claim that african borders were established "as-if random" – is not a bit of a strawman... first because arbitrary ≠ random... second, because I haven't seen many scholars make that claim seriously. it'd be nice to get some quotes of scholars claiming or clearly implying that europeans set those borders "arbitrarily with respect to the realities on the ground"