The Perils of Modern Arms

By Jacob Gerner Hariri and Asger Mose Wingender

Why did representative democracy and bureaucratic government emerge in Western Europe and not elsewhere? The question is so fundamental that the renowned sociologist Theda Skocpol considered efforts to answer it to be the origin of modern social science. The social sciences certainly have produced a lot of answers to the question. Many of them revolve around warfare and conflict in Europe’s past, and therefore, implicitly, around arms technology.

The general story goes something like this: The modern state emerged in Western Europe after the military revolutions of the early modern period when muskets and cannon became the leading technologies of war. Domestically, artillery strengthened rulers against the nobility. Externally, muskets required little training to use and were most effective when fired in volleys, so success on the battlefield required large armies. Mass armies were costly and impossible to field without an extensive bureaucracy collecting taxes, recruiting conscripts, and managing military supply chains. Bureaucrats became as important for winning wars as generals, and interstate rivalry consequently lead to an organizational arms race between the early European states. To pay for their armies of soldiers and bureaucrats, rulers had to grant legal rights to holders of sovereign debt, as well as representation in return for taxes and conscription. Later on, under the threat of revolution in the 19th century, voting rights were extended such that early representative institutions became democratic institutions.

In two recent papers, we show that progress in arms technology since the 19th century has made it increasingly unlikely that countries outside Western Europe would follow a similar path. Wars are now fought with tanks, aircraft, and other technologies unimaginable to people of the past. Such technologies cost substantially more per unit than muskets and cannon, but they also cause far more destruction both per dollar spent and per soldier. Twentieth century arms consequently eased fiscal pressure on governments while simultaneously making the mass army obsolete, thereby severing the link between conscription and representation. To make matters worse, modern arms made it cheaper and easier for authoritarian governments to repress revolutions today than in the past. These findings do not contradict the existing answers to “why Europe?” summarized in the previous paragraph. Instead, they provide an answer to the follow-up question of “why not elsewhere?”.

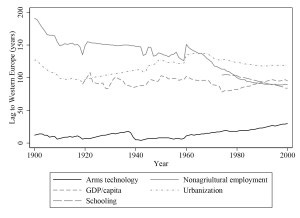

Coercion-Biased Technical Change

An important part of the explanation for “why not elsewhere” is the following empirical regularity: Since the 19th century, most countries in the world have acquired modern arms technology at much earlier stages of socio-economic and bureaucratic development than countries in Western Europe did. (Western off-shoots, such as the United States, are exceptions). Countries that are centuries behind Western Europe in terms of socio-economic modernization are often just decades behind in terms of arms technology. For lack of a better term, we define them as countries with a coercive imbalance.

The notion of imbalance implies a contrast to something balanced. In this context, we consider Western Europe balanced in the sense that the countries in Western Europe developed and adopted arms technology and civilian technology in tandem. Progress in both types of technology accelerated in the 19th century as consequence of the Industrial Revolution. The leading arms producers in Western Europe were private industrialists who had expanded their businesses to include arms production: Krupp and Vickers were steelmakers, Dreyse was a boilermaker, and Armstrong manufactured hydraulic machinery. These industrialists “were able to revolutionize armaments simply by bringing military technology to the level of civil engineering” (McNeill 1982, 278). It was no one-way street, however: Henry Bessemer invented modern steel production to build durable artillery.

The co-evolution of civilian and military technology meant that Western European economies modernized, and popular demand for political rights followed as quickly as governments got access to new means of coercion. Therefore, the balance of power between rulers and their subjects did not change dramatically. Elsewhere things were different. Steel artillery and other arms technologies from Western Europe quickly diffused to the most remote corners of the world, much faster than the Bessemer process for mass-producing steel and other fruits of the Industrial Revolution that would be useful for the civilian economy.

Coercion Works

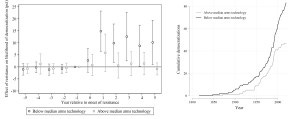

Countries far from Western Europe eagerly adopted the newest arms quite simply because “coercion works; those who apply substantial force to their fellows get compliance and from that draw the advantages of money, goods, deference” (Tilly 1992, 70; Italics in original). Autocratic leaders quickly realized that advanced arms technology allowed a small loyal force to fend off large numbers of unarmed protesters in the streets. Often the mere threat violence was enough to discourage protest movements. Yet both history and current events offer many examples of autocratic regimes using military arms against protesters, and often with success. We estimate that the likelihood of democratization increases significantly after the onset of resistance against the incumbent regime – but only in countries where arms technology is not ahead of economic development. This difference explains why, conditional on GDP per capita, autocracies that have more advanced arms technology than the median autocracy are only half as likely to democratize than autocracies with a less advanced arsenal.

The negative relationship between arms technology and the success of pro-democracy movements is more than just a correlation. In our paper Jumping the Gun: How Dictators got Ahead of their Subjects, we provide evidence pointing to a causal interpretation, and we conclude that progress in arms technology has made popular uprisings less of a headache for autocrats than they had been in the past. Or, in the words of George Orwell:

“[A]ges in which the dominant weapon is expensive or difficult to make will tend to be ages of despotism, whereas when the dominant weapon is cheap and simple, the common people have a chance.”

Herein lies an important answer to “why Europe?”. Participatory political institutions gained traction in Western Europe exactly at a time where inexpensive small arms replaced expensive cavalry as the dominant weapon. In the 20th century, tanks, aircraft and other expensive technologies tilted the balance of power towards despots once more. The emerging middle class of Western Europe was able to take advantage of this window of opportunity as economic modernization and military technology went hand in hand. In countries outside Western Europe, where economic modernization began later, the emerging middle classes faced a much greater hurdle.

No Need for Bureaucracy

Repression of popular resistance is not the only reason arms technology has had a negative effect on institutions. As modern arms made mass armies obsolete and reduced the fiscal requirement of warfare, they also eased the pressure on governments to trade taxes and conscription for democratic concessions. The pressure to develop efficient bureaucracies likewise waned. In our paper Arms Technology and the Coercive Imbalance Outside Western Europe, we explore these effects in a panel of countries from 1850 to 2010. We show that coercive imbalances, as measured by our arms technology data, lead to lower levels of democracy, frequent violent repression, fewer investments in statistical capacity (e.g., censuses), and corrupt and inept bureaucracies. As with democracy, Western Europe had a unique window of opportunity for developing efficient bureaucracies, or, to be more precise, Western European states have been under stronger pressure to do so.

A Pessimistic Outlook

Our findings summarized above suggest that countries in other parts of the world might not follow the same trajectory towards representation and efficient bureaucracy as Western Europe. Although incomes rise and emerging middle classes may demand democracy, the advances in arms technology have tilted the balance of power fundamentally toward their rulers. Our research consequently provides a pessimistic outlook for popular revolutions to succeed in Iran, Venezuela, Russia, and elsewhere.

The insights in this blog post comes from a new comprehensive data set with information on exactly when 29 important arms technologies were adopted by each country in existence since the early 19th century. We are currently expanding and updating the data set to make it part of the Correlates of War database. Until then, the data are available upon request. In this post, we describe how we have used the data. We hope that other researchers will come up with other uses.