The West’s Troubled Origins: Clerics and the Eradication of Europe’s Jews and Muslims

By Şener Aktürk

Why did the West rise above the rest in many indicators of political and economic development starting in the late medieval period? Recent scholarship paid significant attention to the role of the Catholic Church in shaping the West’s rise. Anna Grzymala-Busse discussed “the medieval and religious roots of the European state” in a recent book as well as on Broadstreet. Jonathan Doucette and Jørgen Moller discussed the ecclesiastical roots of representative institutions, including the role of Catholic orders such as the Dominicans as engines of urban representation and self-government, in a recent book and this blogpost. Bruce Bueno de Mesquita argued in an article and in a recent book that the struggle between the European kings and the Catholic Church and its settlement in the Concordat of Worms explains “the birth of the West” and its rise above other civilizations. Similarly, Lisa Blaydes and Christopher Paik demonstrated the contribution of Holy Land crusades to European state formation.

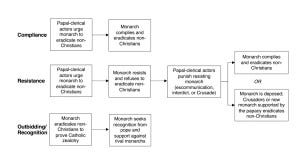

In this scholarly debate, one critical development escaped scholars’ scrutiny: the eradication of Jews, Muslims, and other non-Christians across Western Europe through a mixture of mass expulsions, massacres, and forcible conversions. As I demonstrate in a recent International Security article, “Not So Innocent: Clerics, Monarchs, and the Ethnoreligious Cleansing of Western Europe,” sizeable Jewish and Muslim communities living across Western European polities that correspond to present-day England, France, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, and Spain, were completely eradicated. Three factors led to this development: the dramatic rise in clerical power under papal leadership starting with the Gregorian Reforms in the late 11th century; the dehumanization of Jews and Muslims and their redefinition as royal property by the early 13th century, and the geopolitical division of Western Europe among small polities in a fierce competition for survival since the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. Papal-clerical actors urged monarchs to eradicate non-Christians and sometimes monarchs complied. In some cases (Occitania and Sicily), monarchs “resisted” and were eventually forced into compliance, or even deposed and replaced by more obedient successors. In other cases (Portugal and Spain), monarchs eradicated non-Christians and appealed for papal favors and recognition as the most Christian-Catholic rulers, competing with other Catholic monarchs (Figure 1).

The article’s contribution lies in explicating a supranational, religious, and medieval route to ethnic cleansing, genocide, and demographic engineering, in contrast to explanations that attribute these phenomena to nationalist actors with secular motivations in modern times. In this blog post, I explore and expand the implications of my argument and findings for three other thematic areas of interest for scholars working on historical legacies: the origins of democracy, the formation of Western secularism, and the increase in societal legibility as it relates to identity and administrative capacity.

Representative Institutions and Self-Government for Catholic Christians Only

Muslims constituted the demographic majority in medieval Spain as well as Sicily for many centuries. Spain was home to the largest medieval Jewish population; Jews were the largest non-Christian population in France and the only non-Christian community in medieval England. Jewish and Muslim minorities also existed in medieval Hungary and Portugal. Eventually, all Jewish and Muslim communities in these polities disappeared. All Jews in England and all Muslims in Hungary and Italy were eradicated by the end of the 13th century, whereas the last Jewish and Muslim communities of Western Europe were expelled from Spain in 1492 and 1526, respectively, making all of these Western European polities entirely Catholic Christian. This development was unprecedented in world history, as no other region had previously achieved such a homogenous religious demography.

Is it coincidental that the first inclusive, representative institutions emerged in late medieval Europe exactly at the times and in places where Jews and Muslims were violently eradicated? My preliminary analysis suggests that it is not a coincidence. In “Not So Innocent” (p.105), I critically note that the “Magna Carta (1215) in England included clauses that targeted Jews, and both the Golden Bull (1222) and the Oath of Bereg (1233) in Hungary included clauses that targeted Jews and Muslims.” These documents, justifiably hailed as momentous achievements in limiting executive power, were thus explicitly anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim. Furthermore, this was a broad pattern across Catholic Western Europe, since many anti-monarchical movements seeking to limit executive authority simultaneously targeted Jews and Muslims, defined as serfs of the royal chamber (servi regie camerae). In another pivotal Western polity, France, Jews were “attacked as a proxy for the king himself,” as Stefan Stantchev wrote in Spiritual Rationality (p. 10).

Jonathan Doucette and Jorgen Moller identified the Cluniacs and the Dominicans and Anna Grzymala-Busse identified the Catholic clerical actors more generally as major contributors to democratic development through building the earliest representative institutions such as parliaments and self-governing cities in medieval Europe. Lisa Blaydes and Christopher Paik identified the crusaders as major contributors to state formation and political development in Europe. Complementing this scholarship, I demonstrate that the Cluniacs, the Crusaders, the Dominicans, and the papal-clerical actors more generally were directly involved in the eradication of Jews and Muslims across Western Europe, at the same time as they were building representative institutions for an exclusively Catholic Christian “demos”.

Formations of the Secular in a Western Christian-Only Setting

The eradication of all Muslims and Jews in Western Europe has key implications for the origins and varieties of secularism. In Formations of the Secular, Talal Asad argues that “[t]he concept of minority arises from a specific Christian history: from the dissolution of the bond that was formed immediately after the Reformation between the established Church and the early modern state” (p.174). I focus on and explain a much earlier and more central “bond” between the Catholic Church and the medieval states: A religious sectarian (i.e., Catholic) monopoly was forged in Western Europe through the continental ethnoreligious cleansing that peaked in the 13th century, well before the onset of the Protestant Reformation, and thus predates the “confessional state” by several centuries. This long history of religious-sectarian homogeneity, dating back to the Middle Ages, also helps explain why articulating a European identity that allows “multiple ways of life (and not merely multiple identities) to flourish” (Asad, p.180) has been particularly challenging. Jews and Muslims, with their own laws, rituals, diets, and “ways of life,” were eradicated from Western Europe in the late medieval era and did not come back for centuries (until the 20th century in the case of Muslims).

Significant in this regard is that Charles Taylor’s seminal book, A Secular Age, takes the year 1500 as the reference point of a religious age against which to compare the secular age at present. 1500 is almost exactly the date when the last Jewish (Spanish Jewish, 1492) and Muslim populations (Aragonese Muslims, 1526) were expelled from Western Europe, thus rendering the entire region, at least nominally and publicly, Catholic Christian. The assumed religiosity in Taylor’s Western narrative (and similar narratives of many others) is Roman Catholicism. This is also the case for the “historical baseline” of key works on secularism such as The Origins of Secular Institutions by Zeynep Bulutgil. Relatedly, my argument based on papal-clerical actors’ role as “kingmakers” deposing and replacing dynasties in medieval Western Europe might help explain why the most anti-religious forms of secularism, which prioritize “freedom from religion” rather than “freedom of religion,” developed in historically Catholic polities such as France. Religious authorities were not kingmakers in the regions of the world governed by non-Catholic dynasties, such as Mughal India or the Ottoman Empire. This is the great divide between the Catholic-heritage and the non-Catholic-heritage worlds, overlapping with the West and non-West designation to a considerable degree.

Seeing Like the Catholic Clergy: Maximizing Legibility in Catholic-only Polities

Increasing knowledge of the subject population has been recognized as a key feature of modern state development, conceptualized and popularized as legibility by James Scott in his seminal work Seeing Like a State. Making societies legible increases state capacity, but minorities often pose a particular challenge to maximizing legibility. Volha Charnysh demonstrated in an article in World Politics and in two posts at Broadstreet that the Imperial Russian state had much lower “informational and fiscal capacity… in districts with a larger Muslim population” and that this resulted in far lower famine relief and significantly higher levels of Muslim mortality during the 1891/1892 famine. As I point out in my article, while demographic engineering also occurred in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Europe, its roots go back to the thirteenth century. The first major actor engaged in demographic engineering of continental proportions was the Catholic clergy under papal leadership. In eradicating Jews, Muslims, and other non-Christian minorities, they also increased legibility and state capacity in what became Catholic-only polities, even if this may not have been their primary goal. More intriguingly, such religious sectarian homogeneity was not necessarily the preferred outcome let alone the monarchs’ intention, since Jews and Muslims were monarchical assets as “serfs of the royal chamber” and often allied with the monarchs against the papal-clerical actors.

In “Comparative Politics of Exclusion in Europe and the Americas,” I argued that the persecution of Jews and Muslims “predated the Reformation, going back to the Fourth Lateran Council under Pope Innocent III in 1215.” But why 1215? “Not So Innocent,” alluding to the Pope Innocent III again, provides the answer. Epochal increases in legibility and persecution went hand-in-hand. What R. I. Moore famously described as The Formation of a Persecuting Society in Medieval Europe, entailed a revolutionary increase in “legibility” and administrative capacity, engineered by the Catholic clergy, and foreshadowed totalitarian experiments of modernity. The centuries-long power struggles between the Catholic clergy and the monarchs resulted in nothing less than “the Birth of the West” as Bueno de Mesquita suggests. It is often recognized that this was a violent birth, but that violence was not only interstate violence or the intra-Christian violence that followed the Protestant Reformation, let alone the interstate wars of the 19th and 20th centuries, as many scholars subscribing to the bellicist account of state- and nation-building argued. The birth of the West also entailed a continental ethnoreligious cleansing that eradicated sizeable non-Christian populations and made Western Europe the most religiously homogenous and legible part of the world.