Tracing the Legacy of Southern White Migration

By Samuel Bazzi, Andreas Ferrara, Martin Fiszbein, Thomas Pearson, and Patrick A. Testa

The combination of racial, religious, and economic conservatism—a defining feature of today’s Republican Party—is neither novel nor anomalous in American politics. These three dimensions of American conservatism began to coalesce in the 1960s, marking the birth of a New Right movement that transformed the country’s politics over subsequent decades. In a forthcoming paper, we show how this coalition was influenced by the migration of millions of Southern whites throughout the country during the 20th century. These migrants brought potent new strands of racial and religious conservatism to new parts of America. They joined economic conservatives in building a powerful political reconfiguration that reshaped national politics and hastened partisan realignment, as Democrats lost not only the Southbut also the geographically-diffuse “Southern white diaspora.”

Using electoral data for counties and congressional districts, combined with individual-level data from the Census and the American National Election Survey, we uncover a systematic influence of Southern white migrants—who had settled across vast swaths of the U.S. between 1900 and 1940—on the trajectory of national conservatism. Their large imprint can be seen in the unprecedented third-party run of George Wallace in the 1968 presidential election, the subsequent consolidation of racial and economic conservatism through the Republican Party and its “Long Southern Strategy,” and its later championing of religious conservatism. Besides their direct effects as voters, these migrants shaped conservative values among non-Southern white populations through various channels: they built and led evangelical churches, expanded right-wing media markets, intermarried, and socially interacted with their new neighbors. Through these compositional and spillover effects, this “other” Great Migration of Southern whites reshaped the foundations of policy coalitions in the U.S. at a national level.

In a new working paper, we dig deeper into history to offer a necessary prequel, focused on the smaller-scale—but no less important—influence of the earliest postbellum movers out of the South. Unlike the Southern whites who moved en masse during the 20th century, these early migrants often had direct, personal ties to the institution of slavery. This proximate exposure to slavery, together with antebellum nostalgia and animosity towards federal intervention, would play an important role as they put down roots across America at a critical juncture of nation building and post-war reconciliation.

In our analysis, we track the nearly 1 million Southern whites who left the former Confederacy and allied territory—including an estimated 60,000 former enslavers and another 120,000 of their kin—for the country’s nascent frontier in the three decades after the Civil War. By sorting into positions of authority in local public life, these migrants were able to entrench “Confederate culture” in locales across the United States, with persistent consequences for racial inequity.

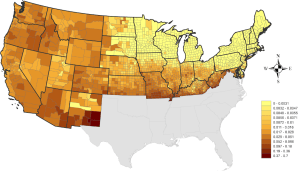

We explore the impacts of Southern white migrants on symbolic and material expressions of Confederate culture in the early 20th century: Confederate memorialization; chapters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC); Ku Klux Klan (KKK) chapters; and lynchings of Black people. We combine these into a single index, as seen below. While Confederate culture was widespread in the South, it was not exclusive to it. We show that the “Confederate diaspora” carried and transmitted these norms across the United States.

These different dimensions of Confederate culture were interrelated. They initially gained prominence within the postbellum South, with shared roots in “Lost Cause” ideology, a set of revisionist narratives that aimed to redeem the image of the South. The UDC was instrumental in the development and diffusion of the Lost Cause through various activities, including its support for Confederate statues and other memorials (e.g., schools and streets named after Confederate generals). Lost Cause narratives offered noble rationalizations for secession and the war, downplaying slavery and emphasizing the defense of states’ rights against Northern aggression. They were full of white supremacist tropes, touting the supposed contentment of slaves and the inferiority of Black people, as just causes for slavery. The UDC and other advocates advanced these narratives across the country, and their symbolic efforts complemented the spread of more overt and violent expressions of racial animus, such as KKK mobilization and lynchings.

The Confederate diaspora also contributed to an extreme form of racial exclusion outside the South, where other, de jureforms were absent. “Sundown towns” became all-white through a process of de facto enforced exclusion of Blacks and other minorities within town limits after sundown. This novel institution spread widely throughout the non-South from 1890–1960 and was more pervasive in areas intensely settled by migrants from the former Confederacy.

Microfoundations of local culture and institutions

To better understand the roots of the Confederate diaspora’s influence, we draw upon the full breadth of complete-count and linked Census data. First, we show that Southern-born migrants, more so than others, sorted disproportionately into influential occupations at destination, becoming judges, lawyers, public administrators, police, and clergy. Such sorting went beyond more general elite entry into high-income occupations, reflecting a taste for or comparative advantage in public authority positions. These sorting patterns—and the Confederate diaspora’s influence in turn—were especially strong in places along the Western frontier that lacked established culture and institutions. This overrepresentation in authority persisted into the diaspora’s second generation.

Second, we link the Confederate diaspora to the re-emergence of the Ku Klux Klan after 1915. In addition to showing connections between Southern white migration and the spread of the 2nd KKK throughout the country, we finding that first- and second-generation Southern whites overrepresented in the KKK in Denver, CO, a major hub of Klan activity in the 1920s for which we can examine complete chapter membership ledgers.

Third, we show that postbellum migrants transmitted Confederate norms to their non-Southern neighbors. In Denver, white men living next door to first- or second-generation Southern whites were significantly more likely to join the Klan themselves. And throughout the country, non-Southern whites were more likely to name their kids after prominent Confederate leaders after moving to locations with a larger diaspora community.

The central role of former slaveholders

Our findings point to a distinct and outsized influence of former enslavers within the diaspora. Such elite influence is consistent with the fact that former slaveholders sorted West and into positions of authority even more so than typical migrants. From these positions of power, former enslavers hastened KKK mobilization and the resurgence of Confederate memory in the early 20th century. Moreover, their impacts were not merely symbolic. This slaveholder diaspora had immediate downstream effects on racial inequity, with Black men raised in counties with a larger former enslaver diaspora being twice as likely to be incarcerated as adults.

A persistent legacy

While we do not deny the influence of other factors, these early impacts of the Confederate diaspora continue to cast a long shadow over the socioeconomic well-being of Black Americans. In places with a larger historical presence of the diaspora, exclusionary sentiment toward Blacks is more prevalent today. In these places, Black residents have relatively lower earnings, experience greater residential segregation, and exhibit higher rates of incarceration and police-induced mortality.

The modern civil rights movement of the 1960s effectively ended most de jure forms of racial discrimination. Yet, racial inequity persists across various critical domains, from education and labor markets to housing and policing. Our study suggests that the persistence of racial inequity despite progressive institutional changes since the 1960s may be partly explained by the entrenchment of racial animus in local norms, institutions, and civil society organizations across the country. Understanding these deep roots of animus may be an important condition for the further dismantling of structural racial inequities.