“We are often told, ‘Colonialism is dead.’ Let us not be deceived or even soothed by that. I say to you, colonialism is not yet dead.” With these words, President Sukarno of Indonesia (pictured) opened the Asian-African conference in Bandung, Indonesia in 1955. Gathered in the audience were the leaders from 29 African and Asian countries, including anti-colonial icons like Ho Chi Minh and Jawaharlal Nehru. The Bandung conference is often fondly remembered today as the moment in the 20th century when formerly colonized peoples around the world joined forces against European colonizers. The Bandung conference, it is often said, heralded the winds of change that swept away most of Europe’s remaining colonies in Africa and Asia. For how, as Sukarno implored his audience, “can we say [colonialism] is dead, so long as vast areas of Asia and Africa are unfree?”

The area that Sukarno most desperately wished to liberate from white rule in 1955 was the island of New Guinea, which at the time was divided equally between the Netherlands and Australia (see Figure 1). The western half of New Guinea, or West Papua, was claimed by the newly independent Indonesian state. And, at Bandung, Sukarno successfully gained unanimous support for Indonesia’s mission to liberate West Papua from the Dutch. Internationally isolated and abandoned by even its Western allies, the Netherlands eventually transferred sovereignty over West Papua to Indonesia in 1963.

If Indonesians expected to be welcomed as liberators in West Papua, however, they were sorely mistaken. Since the 1960s, Indonesia has embarked in a long-running conflict with indigenous Papuans who have sought to establish their own independent nation-state. With a view to knitting West Papua permanently to the rest of the archipelago, the Indonesian state controversially resettled 300,000 farmers from its core islands to West Papua in the 1980s and 90s. This resettlement program, which has displaced thousands of people and made indigenous Papuans a minority in much of the island, has been widely condemned by activists who note its settler colonial character. On the 60th anniversary of the Bandung conference, a leading West Papuan liberation group sent a statement to all foreign embassies in Jakarta, claiming: “It is Indonesia, today, that holds West Papua as a colony.” West Papuans, it seems, agree with Sukarno: colonialism is not yet dead.

It is troubling that the Bandung conference was complicit in producing a condition today in West Papua that looks distinctly like the denial of indigenous self-determination — the very condition that Bandung’s participants were committed to eliminating in 1955. But this paradox is far from unique to West Papua. For Indonesia’s colonization of West Papua is a vexing contradiction that we see again and again across the Global South today in areas like Tibet, the Western Sahara, Kashmir, or Kurdistan. To put it somewhat bluntly: why have so many states around the world rhetorically committed to the elimination of colonialism over the 20th century — like Indonesia, China, Iraq, India, or Morocco — readily displaced minority groups and encouraged migrants to settle their lands?

Why states decolonize

The tensions raised by Indonesia’s colonization of West Papua only deepen once we turn our attention to the eastern half of New Guinea. For if West Papuans were seemingly colonized by a country ideologically committed to decolonization in Indonesia, then Papua New Guineans were decolonized by a country ideologically committed to colonization in Australia. Papua New Guinea was at the vanguard of a White Australian Empire over the twentieth century. Inspired by the United States, Australia’s leaders in the early twentieth century dreamt of realizing their own “Pacific Ocean destiny”, ultimately annexing Papua in 1902 and New Guinea in 1918. Indigenous Papuans were regarded as expendable subjects, and Australia planned to colonize the island with whites.

Yet, Australia ultimately did not turn Papua New Guinea white. Instead, when facing demands from Papua New Guineans for equal citizenship and statehood in the 60s, Australia’s leaders began to push for Papua New Guinea’s independence. Papua New Guinea’s decolonization by Australia in 1975 was a one-sided affair. Australia’s Prime Minister at the time, Gough Whitlam, famously stated that “Men cannot be forced to rule others. [Australia] will not be blackmailed into accepting an unnatural role as rulers” in Papua New Guinea. With Australia’s leaders determined to decolonize Papua New Guinea in the late 20th century, indigenous leaders there could control little but the timing of their own liberation.

The process by which Papua New Guinea gained independence from Australia could easily be written-off as a historical quirk. But the comparison between Papua New Guinea and West Papua is important because it reveals the hollowness of the worldview, expressed by Sukarno at Bandung, that divides the world into colonized and colonizer based on whiteness. Clearly, even the most vocal proponents of decolonization like Indonesia can coercively settle the lands of indigenous peoples. And clearly even white settler states like Australia can, under the right circumstances, become vocal proponents of indigenous sovereignty. Comparing West Papua and Papua New Guinea prompts us to ask an unsettling question: why did Indonesia and not Australia colonize New Guinea?

Recovering the logic of settler colonialism

In my book, Settling for Less: Why States Colonize and Why They Stop, I answer this question by drawing on newly collected data on settler migration from Indonesia, Australia, China, and around the world. I find that all states — regardless of the rhetorical commitments to decolonization or levels of democracy — tend to displace indigenous people from their lands during periods of war and conflict, when they want to populate a contested area with a stereotypically loyal ethnic group. This strategy was first perfected thousands of years ago by the Assyrian, Roman, and Incan Empires. Indeed, the word “colonization” comes from the Latin colonus, or farmer, and was coined to describe the Roman practice of sending farmers to claim newly conquered areas on behalf of the state.

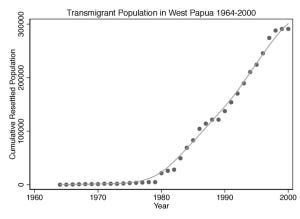

Colonization still proves a brutally effective tool for territorial consolidation today. For instance, in one chapter of the book, and drawing on highly sensitive internal data, I show how Indonesia began to scale up the colonization of West Papua after 1984 following an incursion from West Papuan separatists based in Papua New Guinea (Figure 2). Indonesian settlers or “transmigrants” were sent to low-lying border areas in order to prevent further indigenous incursions, as well as to the most resource-rich areas of West Papua. In other words, Indonesia’s own internal statistical data support the claims long made by indigenous activists like Benny Wenda. West Papua was colonized with settlers in order to prevent its secession and to secure control over its rich natural resources.

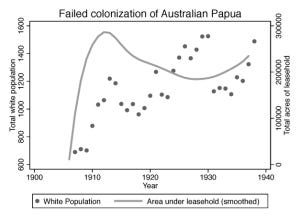

So, why did Australia not similarly colonize Papua New Guinea? In a nutshell: Australia was too rich. In the early 20th century, Australia opened up a large amount of free land in Papua New Guinea for European colonization. But few whites settled there and those that did soon left (Figure 3). There were simply better economic options for European farmers on the Australian mainland where they could access modern amenities and remain close to urban markets.

Indeed, I find Australia and Indonesia both spent almost exactly the same amount of money colonizing New Guinea dollars over the 20th century — approximately $1.5 billion US dollars. With that amount of money, Indonesia sent 300,000 settlers to West Papua at the cost of $5,000 USD per settler, as the promise of free land in New Guinea was extremely attractive to impoverished people across the Indonesian archipelago. Free land was a sufficient incentive for Indonesians to relocate to West Papua. Australia, on the other hand, lured just 1,500 whites to New Guinea at an exorbitant cost of $1 million USD per settler over the 20th century, as it had to buttress the promise of free land for whites with expensive agricultural subsidies and infrastructure. Faced with the prohibitive cost of colonization, Australia quickly pivoted towards the less pricey alternative of simply abandoning the island, and all of its potential liabilities there, to indigenous Papuans in the 1970s.

In short: Papua New Guinea’s decolonization was a direct response to the failure of white colonization. White settler states like Australia lost the power to colonize frontier areas with settlers as they grew richer over the 19th century and as their cities became magnets for migration. Poor countries like Indonesia, Morocco, or China, however, still possessed the power to colonize over the 20th century — much to the lament of dispossessed peoples across the Global South today.

Settling for Less

By placing colonial projects in Western and non-Western states under the same theoretical framework, and by giving equal prominence to positive and negative cases of settler colonialism, my book seeks to overturn our understanding of colonization and prompt us to be more consistent in our political activism. Cases of top-down decolonization like Papua New Guinea or the Philippines, for instance, undermine Patrick Wolfe’s famous claim that white settler states like Australia or the United States are driven by a relentless “logic of elimination” towards indigenous peoples. These cases also undermine James Scott’s claim that modernization and rising state strength spells the end of indigenous autonomy, as states are ostensibly able to send settlers into ever more remote areas.

My work, in fact, shows precisely the opposite dynamic. By eliminating settlers as a political force, economic modernization is a powerful force for indigenous self-determination. For if we are to understand why—exactly contrary to the expectations of Bandung’s participants in 1955—Indonesia colonized West Papua and Australia decolonized Papua New Guinea, then we must understand why Indonesians and not Australians were willing to emigrate to New Guinea for free land. By constraining the practice of colonization, economic development proved the precondition for decolonization both in New Guinea and elsewhere in the world.