Did Tea Drinking Cut Mortality Rates in England?

Policymakers have recently devoted significant attention to elevating the importance of access to clean water as a critical step in advancing economic development, most recently including it as one of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Although significant progress has been made on this front, the World Health Organization estimates that 1-in-3 people lack access to safe drinking water around the world. Since most individuals without access live in the developing world, substantial research in development economics has been devoted to estimating the impact of water interventions on health and mortality.

While these studies highlight the importance of access to clean water in the present day, evaluating the impact of interventions through a historical lens allows researchers to estimate impacts with the benefit of a substantial period over which to estimate long-run impacts. Thus, there are now several historical studies of the relationship between water quality and mortality, though most have largely focused on the U.S. experience in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, by which time clean water and sanitation were already widely understood to have a direct impact on health.

This raises the possibility that treatment estimates are confounded with correlated effects, making claims surrounding the causal impacts of these interventions more contentious. In contrast, my research adds to both the historical and development literatures by exploiting a natural experiment into the effects of water quality on mortality that occurred prior to the understanding that water contamination could compromise health. This occurred through the widespread adoption of tea drinking in England which began in the 18th century. Since brewing tea required boiling water, and boiling water is a method of water purification, the rise of tea consumption in 18th century England would have resulted in an accidental improvement in the relatively poor quality of water available during the Industrial Revolution. To what extent can the rise of tea drinking account for a drop in mortality rates at this crucial juncture in economic history?

Descriptive Evidence of the Impact of Tea on Mortality

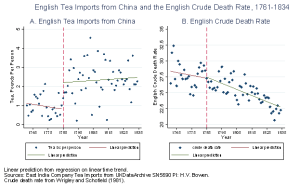

Aggregate statistics at the national level provide descriptive evidence in support of these claims. The above figure links data on English tea imports from China and the English crude death rate over the 1761-1834 period, distinguished by the precipitous drop in the tea tariff in 1785, a major turning point in the widespread adoption of tea as the national beverage. Panel A shows a dramatic increase in tea imports per person from around 1 pound per person at the beginning of this period to almost 3 pounds per person by the end. Panel B shows that over the same period, the English crude death rate fell from around 28 to 23 deaths per 1,000 people, a decline that appears to have accelerated after 1785. Thus, the national picture over this critical period in the development of England, prior to the documented link between water and disease, is marked by a dramatic rise in tea consumption and an impressive drop in mortality rates.

To further bolster the evidence that the mechanism behind these relationships was the improvement in water quality brought about by boiling water for tea, I use cause-specific death data from London collected in Marshall (1832) to show that higher tea imports curbed deaths from water-borne diseases such as dysentery, commonly described as flux or bloody flux (Wrigley and Schofield 1981), but did not significantly affect deaths that were not directly linked to water quality. This is shown in the above figure, where deaths from flux decline with greater tea imports in Panel A, but show no significant relationship to contemporaneous deaths from air-borne diseases such as tuberculosis (consumption) in Panel B. These patterns are consistent with the notion that the special relationship between tea and mortality ran through the consumption of water, and not some other economic explanation. Thus, data from London provide suggestive support for the link between the rise of tea and the drop in mortality, as well as the causal mechanism through boiled water.

Quantifying the Impact of Tea on Mortality

To quantify these effects, I test variants of a simple hypothesis: if tea improved the quality of available drinking water, then we should expect to see a bigger drop in mortality rates in areas where water quality was inherently worse.

In the first empirical strategy, I compare the period before and after the widespread adoption of tea in England, across areas that vary in their initial levels of water quality. I utilize two proxies for initial water quality based on local geographical features: parish elevation and, separately, the number of running water sources in an area, as given by the main rivers near that location. The above figure shows mortality differences across high and low water quality parishes over time, defined by whether they were above or below the median water quality measure (rivers), observed before and after the 1785 drop in the tea tariff which dramatically increased the availability of tea.

While both high and low water quality parishes see a decline in deaths following the widespread adoption of tea, the decline in deaths is larger in lower water quality parishes. This is made clear in Panel B, which graphs the difference in mortality across the two types of parishes (low-high water quality areas). Importantly, the difference across the two types of parishes appears relatively stable prior to the widespread adoption of tea and then dips below zero after 1785, suggesting greater benefits of tea drinking in areas with low water quality relative to areas with better water quality. Results using elevation as the water quality measure show a similar pattern. The above estimates suggest a drop in mortality rates of roughly 25% in low water quality areas, while they dropped by a more modest 7% in better water quality parishes, or an improvement associated with tea on the order of 18%.

The second empirical approach utilizes actual tea import data at the national level interacted with the aforementioned geographical proxies for water quality to investigate whether positive shocks to tea imports resulted in larger declines in mortality rates in areas where water quality was initially worse. The results show that in periods following larger imports of tea, parishes with high and low water quality levels both saw a reduction in mortality rates, but parishes with worse water quality saw a bigger decline. These results hold regardless of whether the parish’s number of water sources or elevation is used as the measure of water quality and are robust to controlling for wages and interacted variables capturing distance to market and alternative imports, thus suggesting the results are not driven by economic factors such as rising incomes or access to trade. The magnitudes of the estimates can be interpreted to suggest that a given increase in tea imports reduced mortality by about 1.4% more in low water quality areas relative to high water quality areas over this period.

Overall, the results from both empirical strategies, using both measures of water quality, and controlling for other time-varying factors at the local level, suggest that tea was associated with larger declines in mortality rates in areas that had worse water quality to begin with. Additional robustness checks rule out alternative mechanisms such as any correlated trends in the prevalence of smallpox or efforts to eradicate it. Thus, the totality of the results point to the importance of tea, and in particular the boiling of water, in reducing mortality rates across England during this important period in economic development.

Although the link between increased tea consumption, health, population, and economic growth has been hypothesized by several historians, including MacFarlane and Mair, this is the first study to provide quantitative evidence on this relationship. At the same time, it is important to note that the estimates herein most certainly represent an underestimate of the impact of improvements in water quality on mortality because tea clearly reduced mortality rates in parishes with relatively good water quality over this period as well as in areas with worse water.

In addition, this study represents an important contribution to the economics and policy literature which has primarily focused on evaluations of large scale government interventions or smaller randomized controlled trials. In this case, water quality was improved without design or costly concerted intervention, but instead through a change in culture and custom that ultimately proved highly beneficial for long-run economic development. As such, current public health policymakers may yet draw lessons from this episode in history as to the importance of cultural adoption to any change in health practice as well as the most cost-effective strategies for improving public health in areas where changes to infrastructure or the adoption of new technologies may not be feasible.