Opium, Empire, and the Symbolic Capacity of Bureaucratic States

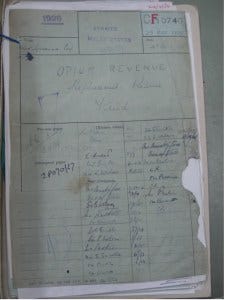

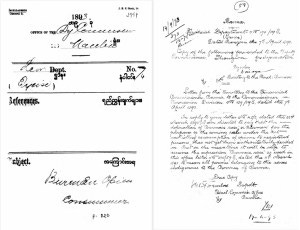

(Cover image of Empires of Vice, from an opium ledger for French Indochina, 1899-1908. Source: FM/INDO NF/88)

The prohibition of opium across Southeast Asia was a great transformation in the history of modern empires and colonial state building. In dialogue with ongoing discussions on state capacity and archives as evidence in HPE research, this post explains how this drug-entangled history brings the symbolic capacity of bureaucratic states and power of fiscal languages about legitimacy to the fore. It also reflects on ways of using colonial official archives for qualitative evidence and interpretive methods.

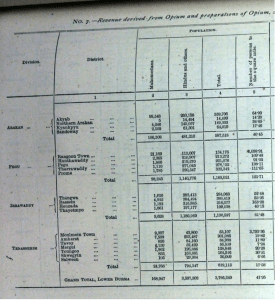

Until the late 19th century, European powers defended opium as integral to running an empire. “Opium was one of things, which enabled us to serve God and Mammon at the same time,” declared the imperial politician George Campbell before Parliament in 1875. During peak years, opium rewarded the British and the French with up to 50% of colonial taxes collected from today’s Singapore, Malaysia and Vietnam; smaller yet still sizable shares between 10-35% sustained colonial rule in Burma, Borneo, Cambodia, Laos as well as the Dutch in Java and the Spanish Philippines.

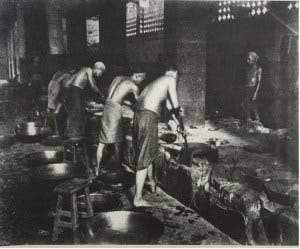

However, into the first half of the 20th century, opium became a dangerous drug that no imperial power would openly acknowledge taxing for profit. They were disavowing the legality of the drug’s economic life, and reconfiguring rationales that had once aligned opium’s contributions to the fiscal might and moral right of imperial rule. Across Southeast Asia, existing opium retail shops and smoking dens faced new restrictions. Major opium factories and packing plants in Saigon, Singapore, and Batavia slowed operations. Interdictions fell upon everyday Burman, Chinese, Malay, Indian, Javanese opium smokers whose habits had long been condoned, indeed encouraged by colonial states.

Opium prohibition as such, was a remarkable reversal to the official mind and practices of European governance over non-European people. It is also, for students of historical political economy, a striking case in which colonial states seemingly abandoned a lucrative source of taxation, contra influential theories following Charles Tilly, Margaret Levi, or James Scott, that view states as guided by efforts to maximize revenue. My recent book, Empires of Vice, endeavors to shed light on what made Southeast Asia’s anti-opium turn possible.

Prevailing scholarship directs attention to the birth of new international norms against drugs, focusing on the role of transnational activists and missionaries, metropolitan drug control regimes, and scientific advances in medical knowledge. But this tends to sidestep a practical and crucial question of how Southeast Asia’s already opium-reliant states were actually able to reconfigure their fiscal foundations and refashion official discourses. What exactly did the nitty-gritty process of colonial state transformation look like? Who did what, when and how to make change possible?

Curiosity about the inner workings of a colonial state pulls one into a vast archive of official records, filled with numbers, categories, and many cryptic, celebratory, bombastic, melodramatic, and rueful statements about opium as a drug, a commodity, an evil, a necessity. I spent around 22 months in repositories across Southeast Asia, Europe, and the United States, focusing on the British and the French—two empires that relied especially heavily on opium revenue from excise taxes—in Burma, Malaya, and Indochina. Because the drug was so deeply enmeshed in colonial governance, records on opium’s fiscal regulation were inseparable from those on customs, immigration, prisons, hospitals, courts, policing, finance and banks. It was a subject matter spanning the highest levels of diplomatic and imperial politics in London, Paris, Geneva, Paris, and Calcutta down to local affairs of managing jails in the Burmese town of Akyab, running mines and plantations across the Malay Archipelago, and everyday policing along long borders with China.

Official archives mentioning opium openly between the late 19th and early 20th centuries capture the most public-facing aspects of the drug’s fiscal and economic life. I wanted to better understand the “raw” material before these “cooked” archives. Archival research often felt like global sleuthing, moving between the Myanmar National Archives and the British Library, digging in the Center for Research Libraries in Chicago, and hopping back and forth across Vietnam’s colonial archives in Hanoi and Aix-en-Provence. I combed records with an eye towards piecing together what had made Prohibition possible. It usually involved tracing who were the authors and calculators of opium statistics and labels for people, tracking what information, biases, and professed standards for authenticity and claims to authority they relied upon, and seeking to contextualize and interpret what interests, ideas and imaginations, strategies were likely at work.

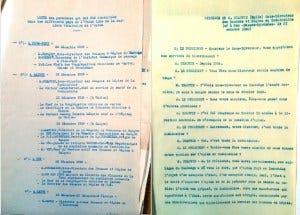

For instance, when in 1930, French Indochina reported its annual net opium revenue and number of legal consumers to the League of Nations, it was helpful to follow Émile Chauvin, the Assistant Director for Customs and Excise for Cochinchina, who had made the calculations. He left traces in an exchange on December 21, 1929 with the League’s representative, a Swedish diplomat named Einar Ekstrand, which later clued me to major opium supply crises. Or in 1924 Singapore, when the British launched an opium revenue replacement reserve fund to reduce its fiscal dependency on the drug, I chased down Arthur Meek Pountney, the Oxford-educated math whiz who designed this policy.

What is the larger story that emerges from these sources? What explains the rise of opium prohibition across Southeast Asia? My core argument centers on bureaucracies and their symbolic capacity to define problems. Prohibiting opium, I contend, was a slow and incremental process, enabled by a loss of confidence among the state’s own actors about the drug’s contributions to colonial rule. Low and mid-level administrators on the ground played pivotal roles by constructing official problems about opium, which eroded its fiscal legitimacy from within.

For in spite of its largesse, opium had never been an easy thing for colonial states to manage, largely due to how the drug’s consumption across Southeast Asia was taxed as a colonial vice.

Think of a sort of original sin. In 1819 Singapore or 1860 Saigon—founding moments when European colonizers began to root territorial claims—local administrators on-site started to tax opium smoking as a peculiar vice among the colonized, without clear conceptions from a regulatory perspective about what exactly defined a colonial vice; why it was a fiscal object; let alone what justified the state’s involvement.

To borrow Hugh Heclo’s felicitous formulation, if states usually puzzle before they power—figuring out who and what they are governing, categorizing and collecting information about society—the opposite happened with regards to opium consumption in Southeast Asia. Colonial states powered before they puzzled. This sort of reverse sequencing would become an enduring source of tensions for subsequent administrators.

By tensions, I mean initially petty issues, annoyances of everyday bureaucratic work, such as vague labels and borrowed classification schemes that ill-fit perceived reality. For instance, British Burma’s Excise Department initially borrowed templates from Bengal that used religion-based categories to count opium consumers. Soon, local administrators tried to fix the fact that in a Buddhist-majority colony, nearly all of their enumerated opium population fell in the residual category of “other.” They hurriedly altered the headings of opium excise reports to use labels of Burman (even as the official definition of Burman remained unspecified) and non-Burman, later adding Chinese and Indian.

Such petty tasks were the stuff of everyday opium taxation and regulation. It was repetitive, habitual, and sometimes, grimly comical. Tensions were solved in makeshift ways that begot larger problems over time. By way of recursively solving problems of their own making, minor bureaucrats gave official reality to perceived threats to colonial governance that slowly accumulated, escalated, and became taken-for-granted reasons for the state to take action against opium. The emphasis here is on slow. In British Burma, it took 20 years for an official problem definition of social disorder caused by “morally wrecked” Burmans to emerge, which enabled the first European ban in 1894 on popular opium consumption in a Southeast Asian colony. Different contexts gave content to different types of opium problems, such as an unsustainable fiscal dependency on opium revenue in British Malaya (between the 1890s and 1920s), or a dangerously high reliance on opium imports in French Indochina (from the 1920s to 1940s).

Empires of Vice traces these processes. Theoretically, I refer to them as bureaucratic constructions of official problems: a mechanism through which symbolic state capacity is built by defining politically actionable dangers. Low and mid-level administrators wielded extraordinary discretionary power at this micro-level of state activity, by defining problems worth solving, authorizing facts on the ground, making up categories and crafting numbers that served as the evidentiary basis for macro-level legal and policy changes. They were seemingly weak actors with surprisingly strong powers, who played informational and interpretive roles doing the backend work for making socioeconomic worlds administratively legible. And hardly deliberately, yet still not in spite of themselves, these minor bureaucrats enabled a major state transformation to occur.

Stepping back, this complements how a vibrant tradition of HPE is studying the state and the origins of its capacity, and finding historical data.

First, it sharpens our attention toward symbolic state capacity—a capacity “to name, to identify, to categorize, to state what is what and who is who” in ways that constitute as given, what is in fact a product of human action—and how this capacity emerges and evolves over time. Influential studies on the historical accumulation of symbolic capacity and construction of taken-for-granted political authority focus on state-society interactions. Opium prohibition in Southeast Asia attunes us to what goes on inside the state, and endogenous sources of change stemming from intra-bureaucratic struggles over category formation and official knowledge making.

Second, working through official archives for qualitative evidence and interpretive inquiry is intimately tied to narrative choices: how to portray the actors we encounter in historical context, how to emplot their actions and meaning. As a matter of method, I approached process tracing in a rather unconventional sense of storytelling. It involved connecting sequences of concatenated ideas and actions “whose final outcome is necessarily hidden from the proponents of the individual links” but nevertheless propelled through their words, deeds, and decisions.[1]

As a matter of politics, given my particular topic and time period of opium prohibition in 19th and 20th century Southeast Asia, I grappled with normative challenges over how to write about colonial bureaucrats who were solving perceived problems that they themselves had helped create. These were unmistakably agents of structural domination, a large enterprise of empire building and colonial rule profoundly injurious to the dignity, health, and survival of so many people. But these actors were also doing oddly creative work, and their official languages were not always mere smokescreens for base interests, but also expressed struggles to find meaning in their actions. I found this both uncomfortable and valuable. Personally, it was a constant reminder for caution about the practical implications to my telling of another’s colonial history. Analytically, it pushed me to grapple with the time-old question about the “official mind” of a state, in terms of what do we mean when we say the state wanted, or intended certain things and their (unintended) consequences.

—

[1] Hirschman, Albert. 2013 [1977]. The Passions and the Interests: Political Arguments for Capitalism Before Its Triumph. Princeton University Press.